Peru: Titicaca Lake (Puno, Taquile, Uros)

Pubblicato: 16.10.2018

Iscriviti alla Newsletter

Onwards to Lake Titicaca! This would be our last journey on the comfortable Cruz del Sur bus, so we enjoyed the last few hours in the luxury bus.

Puno itself doesn't offer much. Our first impression was that it's a tourist hole, but not as much as the town of Copacabana on the Bolivian side of the lake, as we would later find out.

Our hotel was located directly across from a small square where young people would meet every evening to play music and dance. The hotel employee told us that they were members of dance groups or student associations who practiced there for performances. I really liked this atmosphere, even though it was sometimes chaotic (and occasionally exhausting for the ears) when 3 groups practiced different music pieces at the same time.

A former colleague of Jörg was on vacation in Peru with his friends at the same time, and they would arrive in Puno one day later than us. For this reason, we decided to stay in Puno a little longer to wait for the guys.

First, we took the Collectivo about 30 minutes to the village of Chucuito. After we arrived at the main square, we had lunch at a small local restaurant where they served Chicharron de Pollo. Then we made our way to the Temple of Fertility. The "temple" is a small building with many stone penises. Big and small, some up to 1.2 meters long. Interestingly, the tower of the neighboring church is adorned not with a cross, but with a penis. Actually, the whole thing is not particularly spectacular, but quite funny. Just as we were there, 3 women of different ages arrived and we all had a great time taking photos of ourselves with the penises in different poses. Even the grandma, after some persuasion from her colleagues, dared to hug the biggest one for a photo and stick out her tongue lustfully.

Afterwards, we enjoyed the view of the lake, wandered around the village a bit, and sat in the pretty park for a while.

Visiting the Temple of Fertility is not a full day program, but still quite entertaining.

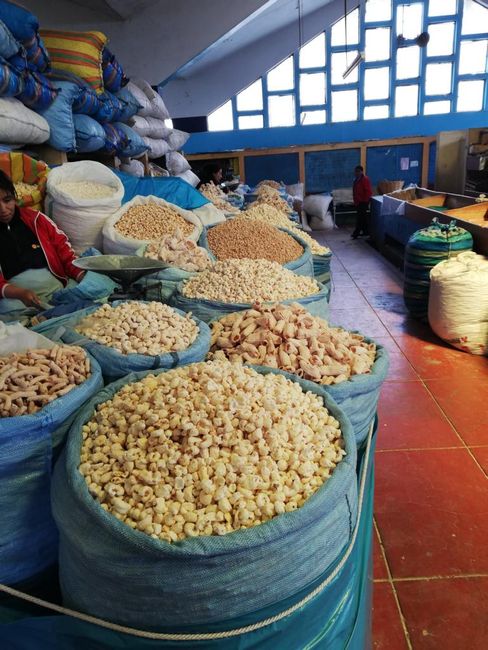

On the way back, we visited the vegetable market in Puno, where we stocked up on fruits. Jörg, or rather his height, was once again the highlight there, as all the market women started talking to us and were very excited.

For the next day, we booked a trip to Taquile Island. The boat trip from Puno to Taquile takes about 3 hours, as the island is located on the open lake, outside the bay of Puno. Since we requested a tour in Spanish, there were only local tourists on the tour with us. Interestingly, there was a group of people from Cusco, dressed in traditional colorful costumes. These women, who usually ask tourists for tips for photos, were now tourists themselves. So, we practically had the typical Peruvian photo subject right there with us.

Taquile Island has been inhabited for thousands of years and feels like its own little world. It is very quiet here, there are no vehicles like cars or motorcycles, all distances have to be covered on foot. This is quite a challenge, as the long and steep ascent from the boat port to the village is very strenuous, especially at over 4000 meters above sea level (Lake Titicaca is the highest navigable lake in the world). The island is particularly known for the traditional knitting of woolen goods (UNESCO). Boys have to learn knitting at the age of 8. The local men wear knitted caps, and based on their colors, you can tell if they are still available or already married. The island also has a long tradition of weaving, which is primarily women's work. The woven patterns and animal figures are incredibly fine and detailed.

When we reached the highest point of the island, the weavers were already waiting for us to demonstrate their craft. As the guide explained to us, this was a special program because the weavers from Cusco had asked for an exchange with the women living here. The tourists on the gringo tour didn't get to see that. So, it was once again a big advantage to speak Spanish, as it was very interesting to see the women sitting together and discussing their craft. Unfortunately, the introductions and conversations were in Quechua, and although our guide tried to translate for us, we didn't understand many details. But it would have been too much to learn Quechua in such a short time. Nevertheless, it was very entertaining and we were able to take some nice photos (even without a tip). Interestingly, the Cusco weavers didn't buy anything from the Taquile weavers, which I found a bit disappointing. So much for mutual exchange, as they always want to sell us something.

Then we walked across the island to the village. On the way, we enjoyed the wonderful view of the lake, the island, and the village. In the village, we had lunch and then had some time to explore on our own.

On the way back, we made a stop in Uros, the village made up of reed islands. But for us, it was only moderately interesting. Actually, we didn't want to go there because we had already booked an overnight stay on one of those reed islands for the next day, which, as we would later find out, was also more authentic. But more on that later.

In the evening, we finally met up with Jörg's colleague Tobias and his friends Paul and Dominic. First, we had some drinks and then went to have pizza. The pizza was the worst I have ever had, but the company was very pleasant, and we had a fun evening together. It's funny when you randomly meet someone at the other end of the world. Interestingly, the guys were staying at the same hotel as us, so we also saw them again in the morning during breakfast and said goodbye. They were only traveling for a few weeks and would continue to Bolivia right away, while we would stay here at Lake Titicaca a little longer.

After breakfast, we were picked up soon after. Now it was time to go to the Uros! They are a people who live on artificial reed islands that they have been making themselves out of totora reeds for centuries. The community consists of about 90 of these islands, each with its own name. Unfortunately, the place has become completely commercialized, but there is still nothing comparable anywhere else.

Among other things, there are several reed hotels where tourists can stay. But as we were told, almost all of these hotels belong to agencies in Lima or Cusco, to people who are not from here themselves. We had booked our stay at the Uros Samaraña Uta Lodge. The taxi that picked us up at the hotel took us to a small boat dock outside of Puno, where Cesar, the owner of the lodge, was already waiting for us. Cesar and his wife Lucia were born here and have spent their whole lives here. Cesar was fortunate that his parents sent him to Puno for his studies, so he knows a bit about IT and can promote his self-built hotel on the internet. The people in the village admire him for what he has achieved without depending on the big agencies. He explained to us that there are 2 schools in the community, but the vast majority of children only complete primary school. The village also has a "hospital" where a doctor from Puno occasionally comes by. But since he only comes irregularly, few people here take advantage of his services. In general, people here don't get seriously ill, according to Cesar. For example, there is no cancer here. However, osteoarthritis is a problem because very few people ever wear shoes, and walking on the reeds all the time makes it difficult for them to walk as they get older. Therefore, it is common for children to eventually take care of their parents if they can no longer move on their own. Otherwise, they rely on traditional healing methods. Cesar tells us that there is a lot of corruption here in Uros. The locals have become highly dependent on tourism, but they have no direct access to the tourists themselves, instead relying on tourist agencies and boat operators who bring the guests. For example, each island has to build and provide a typical tourist boat made of totora. If the islanders don't do that, the tour boats won't go to their island. To visit the Uros community, a fee must be paid at the entrance to the village. However, this fee is solely used to keep the area clean, dispose of waste, and pay for general offices (such as the community president and administration). The local people mainly benefit from tourism through the sale of handicrafts, and they even have to pay commission to the tour operators for that. They have tried to revolt against the agencies and go on "strike." But then the operators simply started building their own "fake islands" elsewhere and stopped bringing tourists here. In fact, Jörg and I came to the conclusion that one of the islands we briefly visited the day before with our Taquile tour was also a "fake island," as the construction was very different from what we found here. That could only mean that the tour operator pocketed the Uros entrance fee that we had paid, even though we didn't actually want to go there.

After we arrived on the small reed island where we would call home for the next 2 days, we were assigned our bungalow and allowed to look around. There wasn't much to see because the island is quite small and there is only water all around. The accommodation was simple but functional. We even had our own bathroom with a compost toilet in our bungalow. The shower had to be shared, and the water is heated with solar panels. In fact, almost all the islands now have solar panels. This hasn't been the case for long, Cesar explains, as there hasn't been electricity here for very long. It is an important achievement for the people here because previously they only had candlelight, and there was a risk of the whole island going up in flames if an unattended candle fell over.

There is no heating, but since it gets very cold at night, there were plenty of blankets, and after dinner, we were given bottles wrapped in fabric filled with hot water, which surprisingly kept the bed warm throughout the night.

Soon after our arrival, we went on our first excursion. Cesar took us on a boat tour through the entire community. Then we stopped at a larger island where several families lived together. There, they demonstrated how the islands are built using a sweet model. During the rainy season, parts of the peat on which the totora reeds grow detach from the ground and begin to float on the water's surface. These peat areas are collected and tied together. Then large quantities of reeds are cut and laid in several layers over the entire island to prevent moisture from below. This process has to be repeated over and over again, and the reeds on the island have to be renewed every 2 weeks. New reeds are simply laid over the old ones. The lower layers will eventually deteriorate and turn into new soil, making the whole construction stable. Cesar tells us that they tried to replicate the reed islands in Bolivia. However, they took aluminum floats and coated them with totora. The next storm wind blew all the reeds from the metal. Actually, the biggest danger for the islands is the wind. Therefore, after they are brought to their destination, the island is secured to the ground with several wooden stakes. But it has already happened that families found themselves along with their island and house far out on the lake after a stormy night.

When we returned from the tour, a small boat loaded with reeds arrived at our lodge. There was a damage on the island that needed to be repaired, a edge had become unstable and was about to slide off. So, we had the chance to watch how the damage was repaired: old reeds were removed, several wooden slats were placed underneath to stabilize the sliding edge, and then several thick layers of new reeds were laid. It is truly hard work, and it has to be done every two weeks on the whole island.

After lunch, Lucia took us on a ride in a small totora boat. She paddled us by hand a bit away from the hotel island to check a fishing net that she had set the day before. She explained to us that she only sets this net now to show tourists her everyday life. In the past, it was still possible to fish all around the community, but nowadays there are hardly any fish left. The fishermen have to go far out onto the lake to catch enough. She told us that when she was young, she used to spend the night on the boat with her family next to the laid-out nets because her father always wanted to check on the nets. It was very cold at night on the lake, but the whole family cuddled up on the small boat. Lucia speaks with such a gentle and soft voice that it sends chills down your spine. Everything she does, she does calmly and deliberately. You can tell that this woman has never experienced stress in her life, has never been under time pressure. She tells us that she couldn't imagine living anywhere else outside of Uros, she has never been anywhere else. When she has to go to Puno on Saturdays to go shopping, the big city scares her. She fears the traffic and the hustle and bustle, and she also always worries about her two children that they might run in front of a car. While we drift on the lake and watch the sunset, she tells us about the traditions in Uros. A couple comes together at a very young age, and with the chosen partner, they will stay together for life, in good times and bad, there is no divorce here. In the past, marriages were arranged, but nowadays young people are allowed to choose for themselves. First, the couple will live together for a few years to save up for the wedding. During this time, the couples already have children, there is no problem with illegitimate children here. The couple can only get married when they have enough money to invite the whole community to the wedding celebration. The ceremony takes place in a church in Puno, and then there is a celebration on the islands. If the island where the couple lives is too small, several islands are simply pushed together. The festival lasts for 3 days, she tells us.

The next morning, Lucia showed us how the Uros make gifts and souvenirs out of totora reeds for the tourists. We were allowed to make a small souvenir ourselves as well. Lucia also dressed us up in traditional clothes and braided my hair to take some funny photos.

Then we went out on the totora boat again to pull up the fishing net. In the meantime, 4 fish had gotten caught in the net, a good catch for the area, according to Lucia. However, the local fish are very small. The trout that can be caught in Lake Titicaca were introduced.

On the way back, we made a stop at a reed field. Suddenly, Lucia pulled an egg out of the reeds and showed us the nest she had found there. In addition to fishing, the Uros also live from bird hunting and egg collecting. They cannot do agriculture on the islands. Traditionally, they meet with indigenous people from the mountains on Sundays and exchange fish for potatoes and vegetables.

After returning to our little island, it was time to say goodbye. We felt a little nostalgic because Cesar and Lucia had welcomed us warmly into their home and had spent a lot of time showing us their culture and way of life. Our stay in Uros was truly incredibly interesting and educational. Finding another people like this on Earth won't be easy. On the reed islands, you feel so far away from civilization and the modern world, even though you are only a 30-minute boat ride away from the big city of Puno. That is truly special.

On the one hand, I do feel a bit sorry for the Uros that they are so dependent on these tour operators and travel agencies and are being exploited by them. On the other hand, I also miss a bit more initiative and drive, because it would certainly be possible for the people in Uros to set up their own travel agency with their own excursion boat in Puno and market their own tour. Especially since eco-tourism is so popular nowadays, such a business would certainly have good prospects, as can be seen from the example of the lodge we stayed at. But there is probably a lack of education and cooperation. An example of this is that there is no school boat in the community that collects all the children. Lucia goes out in her own boat every morning to take the children to school and pick them up later. And every family does the same. This is certainly not very efficient. Moreover, it is interesting that the exact same souvenirs are sold at every place, on every island. Everyone offers mobiles and small boats made of totora reeds. A little more creativity would certainly be helpful.

Cesar said that they feel pretty forgotten by the Peruvian state here. However, personally, I have mixed feelings about this statement. Of course, if you live on the edge of civilization like this, you may develop this feeling. And yet the state sends doctors and teachers, which is better than nothing. And in the end, it is also their choice to live as they do. Their choice not to send their children to a secondary school. Their choice not to use modern medicine. Apart from that, it should also be mentioned that the Uros do not pay any taxes.

Another aspect that made me think is the definition of prosperity in this place. Cesar and his family are considered wealthy in the community because they have their own small hotel and earn good money with the tourists. But what does prosperity actually mean on a reed island? Despite everything, they still live in a small reed house on a floating totora island. They have one more boat than the other families, which they need to drive the tourists around. They may have a few more solar panels because they have to illuminate several bungalows. They have a mobile phone that they need to manage the bookings on the internet. They may have better food, more variety on their plate. And they no longer have to repair the damage on their island themselves. They have hired a boy to lay out the totora reeds, while Cesar picks up and drives the tourists and his wife cooks for the tourists and tells them about the local traditions. But what else? There are no expensive furniture, no fancy cars, no fashionable clothes, and no trips to distant countries. Status symbols seem to have little meaning here. I have probably never seen such a fine difference between rich and poor as here on the Uros islands.

It was truly a fascinating experience, our time here with the Uros, we saw and learned a lot of new things. Looking back, this was definitely one of the highlights of our entire stay in Peru.

And that's it, our time here in Peru. The next day we would continue to the Bolivian side of Lake Titicaca.

Peru. What can one say about this country? Honestly, at first, we didn't like it that much. And yet we spent a total of 8 weeks here. Normally, they say that the advantage of long-term travel is that you can just stay where you like it and run away from where you don't. My theory is that it is better to see everything that interests you where you don't like it because then you have seen it and don't have to come back later. After all, you happily return to a place where you liked it. And Peru really has a lot to offer, there is so much to see, and some of the highlights of the entire continent can be found here. The country is so rich in culture and history, but there are also adventures to be had, culinary highs to enjoy, and landscapes to admire.

And it is fair to say that it got better as we headed south. The people became friendlier than they were in the north, we felt more welcome and not just tolerated.

For us, who like to do things on our own, it was annoying that many things can only be done on a guided tour. It was even more annoying to constantly be rushed and herded around. On the other hand, it is a sympathetic characteristic that everywhere they try to show tourists everything there is to see about a place, and so often way too much program is packed into the tours, making stress unavoidable.

However, all of this also makes Peru a country that is easy to travel, even if you don't speak Spanish and/or have little travel experience. You can really get around the country easily, the buses are very good, and there is a wide range of guided tours and activities everywhere that can be booked at short notice. We never felt unsafe anywhere.

Although the journey through the country cost us a lot of nerves at times, we still enjoyed the time, we saw and experienced a lot, and we will take many great memories with us.

Iscriviti alla Newsletter

Risposta

Rapporti di viaggio Perù