Mit Geschichte(n) um die Welt

vakantio.de/mitgeschichteumdiewelt

The Katyń Museum. Or: Insider tips for Warsaw

Ku kandziyisiwile: 19.09.2024

Tsarisa eka Xiphephana xa Mahungu

You can easily spend a whole day at the Warsaw Citadel. The grounds are large, today more of a park, along with several museums, outdoor exhibitions, and monuments. By 2026, the massive building “Museum of the History of Poland” will also be added. By then, 24 hours on the Citadel grounds will no longer be sufficient. However, a visit is already worthwhile, and the following will mainly focus on the Katyń Museum [Katyń pronounced approximately “Katijnn”].

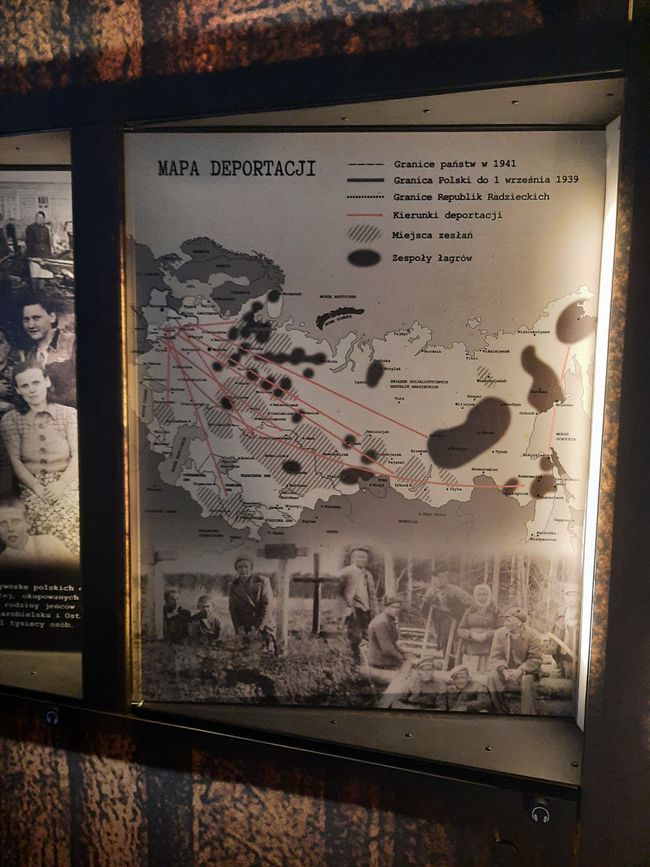

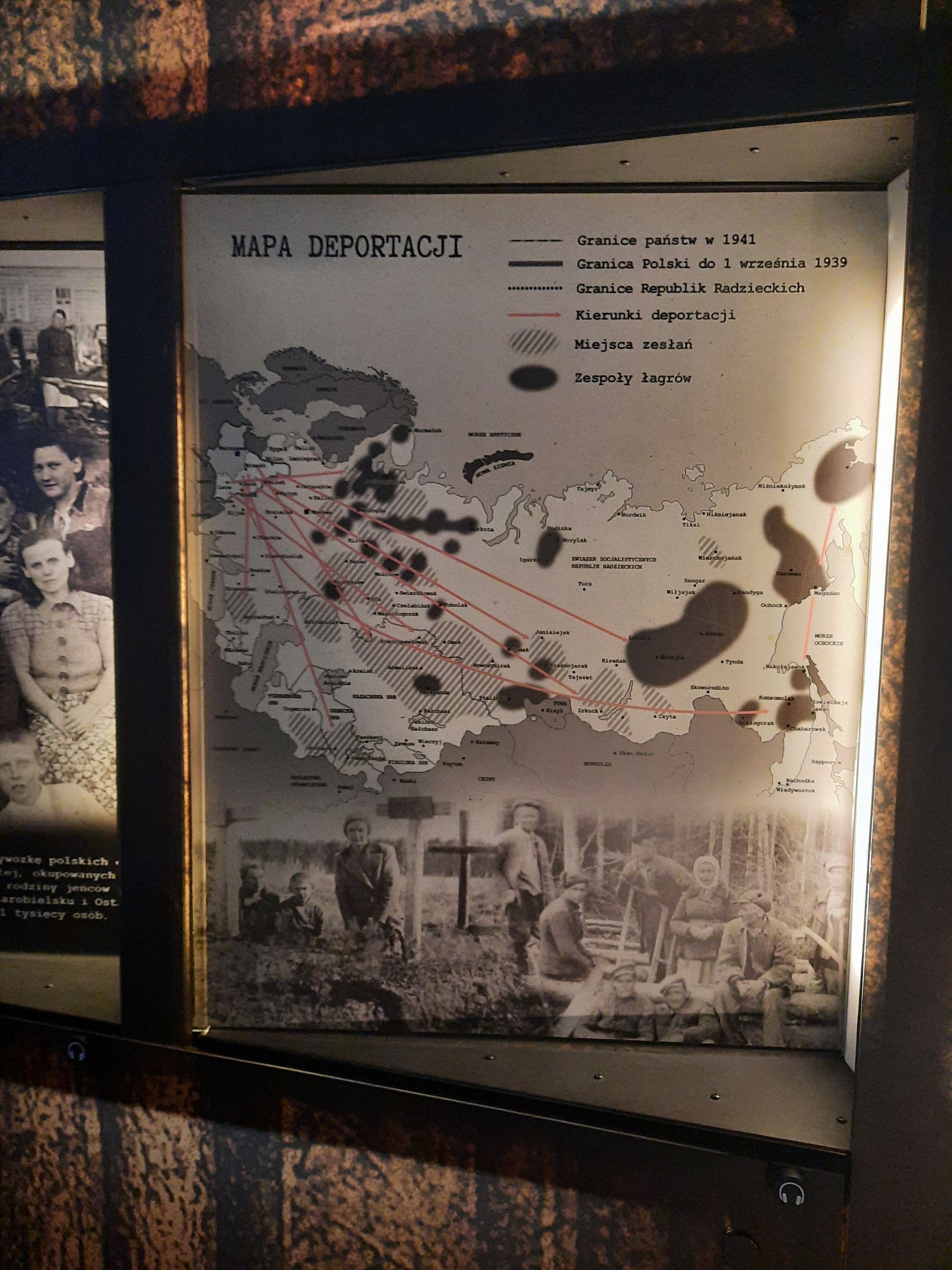

The museum is not new. It has existed in its current form since September 17, 2015. The opening date was symbolic, like so much in Poland: it marked the 76th anniversary of the Soviet invasion in eastern Poland in 1939 - 17 days after the German Wehrmacht invaded the west. Subsequently, tens of thousands of Polish prisoners of war were captured by both occupying powers, Poland was divided, Polish citizens were expelled, murdered, and deported. The Soviet Union abducted “its” prisoners of war, both Polish men and women, their relatives, and many other tens of thousands starting from 1939 into the depths of the Soviet Union.

In 1940, the Soviet secret service NKVD murdered about 20,000 of these Polish prisoners of war. These mass executions took place in various locations. The most well-known is Katyń, not far from Smolensk in western Russia. When talking about “the Katyń crime,” it is a cipher in Poland. It refers to the murder of Polish officers and soldiers near Smolensk, as well as in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Mednoje in the Russian Tver Oblast, Kuropaty near Minsk, and possibly other places. It also stands for a long-silenced crime, historical distortion, and manipulation.

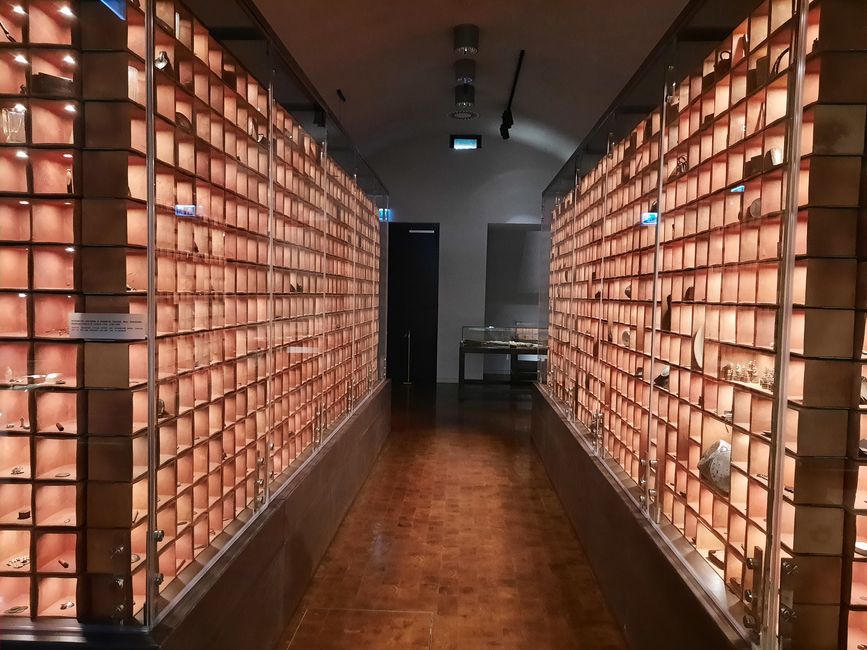

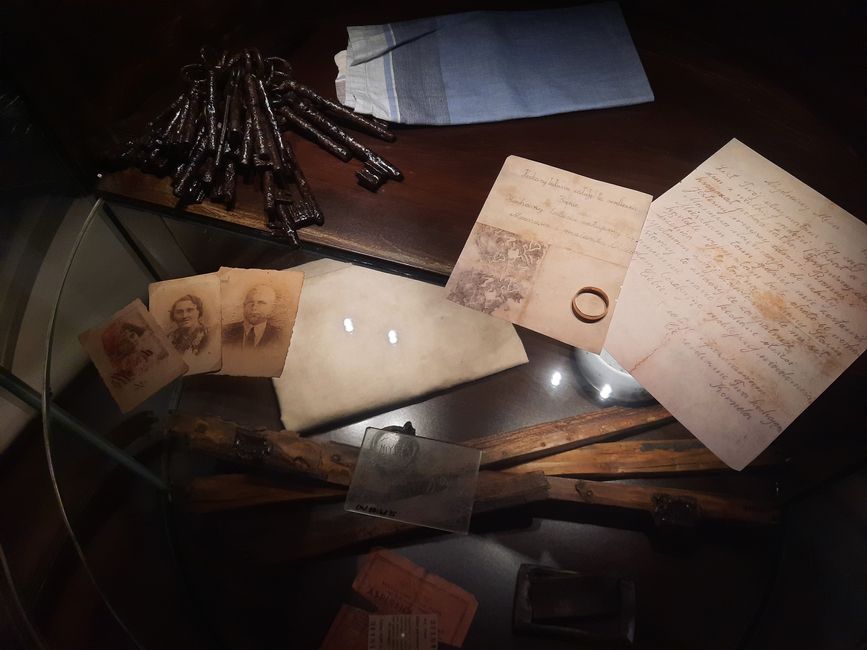

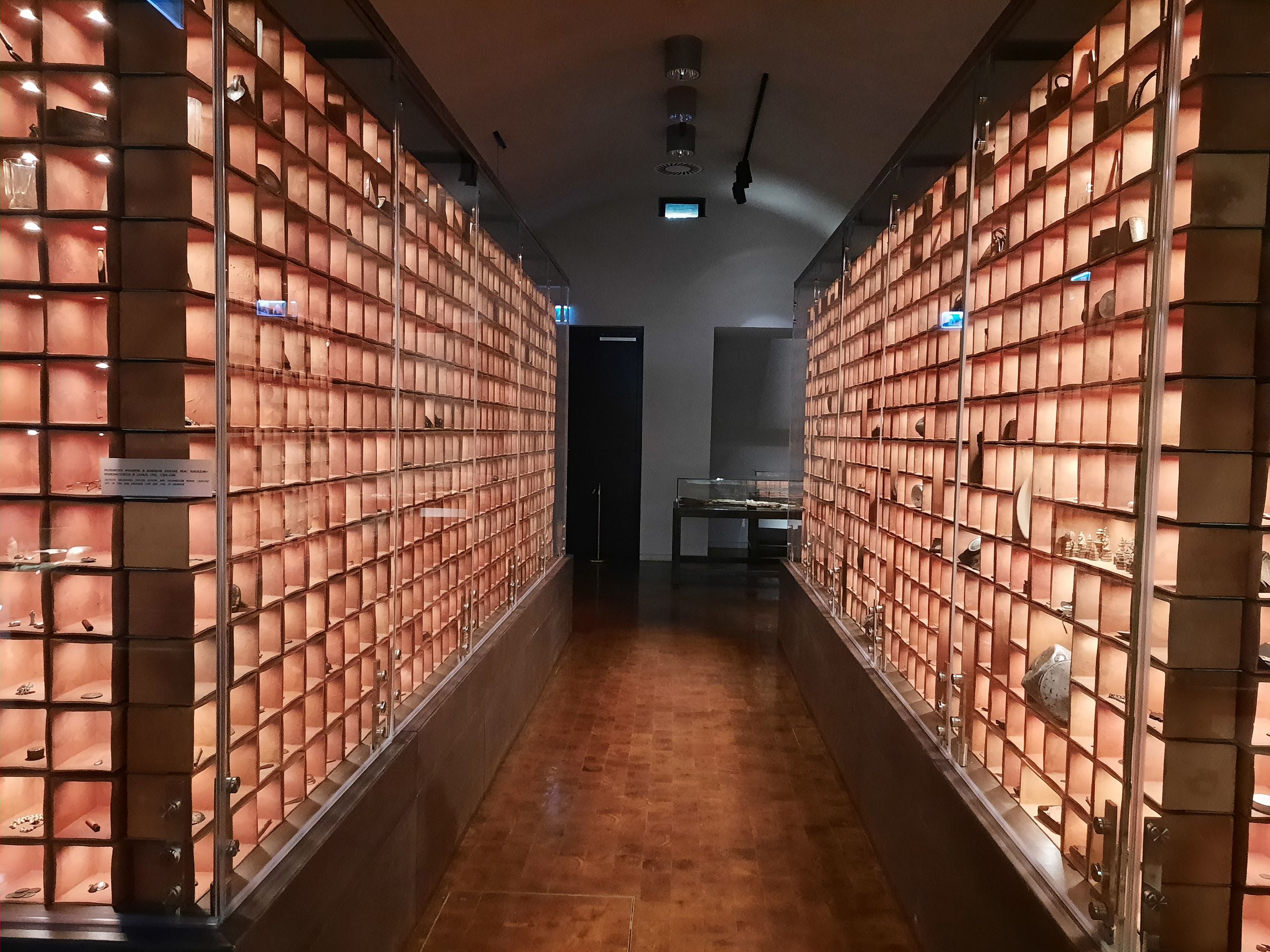

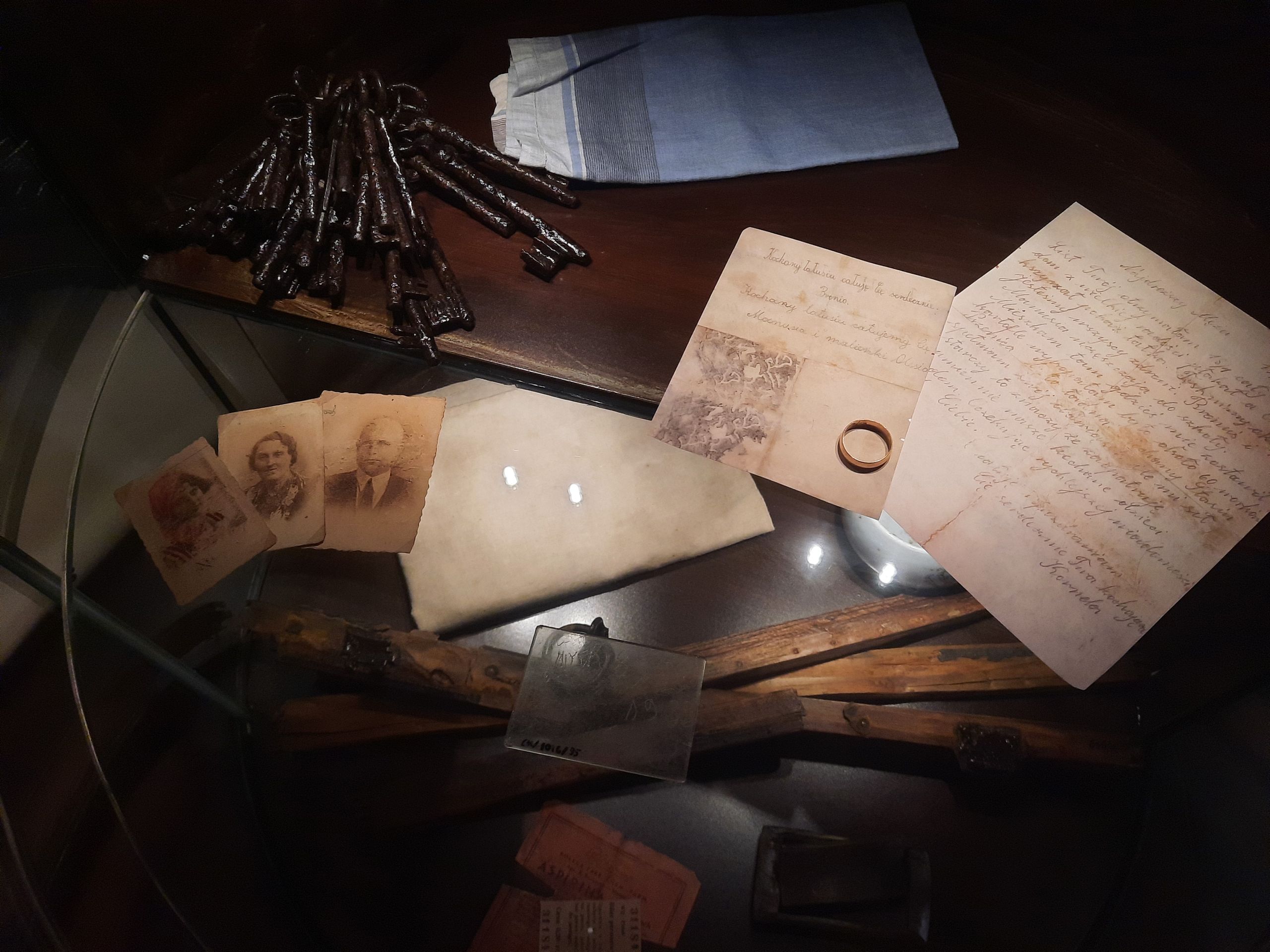

The Katyń Museum tells exactly these stories: those of deportations to the eastern and northern Soviet Union as well as to Central Asia; those of often still nameless soldiers from Poland; and those of a politically highly explosive and often abused past. It talks about concealing and revealing these mass executions. And it showcases thousands of objects found during excavations at various shooting sites in the 1990s. This sheer mass of items can be overwhelming at first glance - yet upon closer inspection allows for a concrete connection to the nameless fate of an individual. The exhibition is impressive, and although most of the display panels are in Polish, an audio guide is available in other languages.

Tableware, letters, rings, photos, buttons, pieces of uniforms, amulets, military badges, wallets, watches, cigarette cases, everything found in the 1990s - and what was left after multiple exhumations had already taken place on site.

Remarkably, the first exhumation was organized by the German occupiers during World War II. The Nazis were aware that “their” find of the murdered Polish prisoners of war should be something that could be exploited for their own propaganda. The Soviet Union as the great enemy, as those - in this sense the only ones - who would commit and had committed a humanitarian catastrophe. The crime had tremendous political explosive potential. The negotiations conducted after the German attack on the Soviet Union between the Polish exile government and Stalin, which led to the founding of the so-called Polish “Anders Army” (see blog post about Monte Cassino), broke off. The accusations weighed too heavily; the Soviet Union remained silent - and accused the Germans of the crimes. After 1944/45, the Allies - and thus also the USA and Great Britain - excluded the crimes from legal prosecution. Exiled Poles condemned the Soviet crimes: Katyń, the great symbol, showed that the Soviet Union was also a criminal nation, against which one had to oppose, which had brought calamity to Eastern Europe (and in this sense would continue to do so). However, the voices of exiled Poles were barely heard. In the People's Republic of Poland, the murders were hushed up or alternatively attributed to the German occupiers.

Remembering and warning in exile

A true (counter) remembrance could only take place in the Polish diaspora in the western world. The bearers of this memory were mainly those who narrowly escaped the massacre: those who from 1941/42/43 first became part of the “Anders Army” (under General Władysław Anders) and then of the 2nd Polish Corps (see here on the blog). One of the central tasks of these (exile) Polish veterans' associations became the commemoration of the victims of Katyń and the exposure of Soviet crimes against Polish citizens, including the mass deportations after 17.9.1939. Today, those who trace the footsteps of Polish Displaced Persons around the world will find Katyń memorials. One of the first outside Europe was erected in the Australian Adelaide .

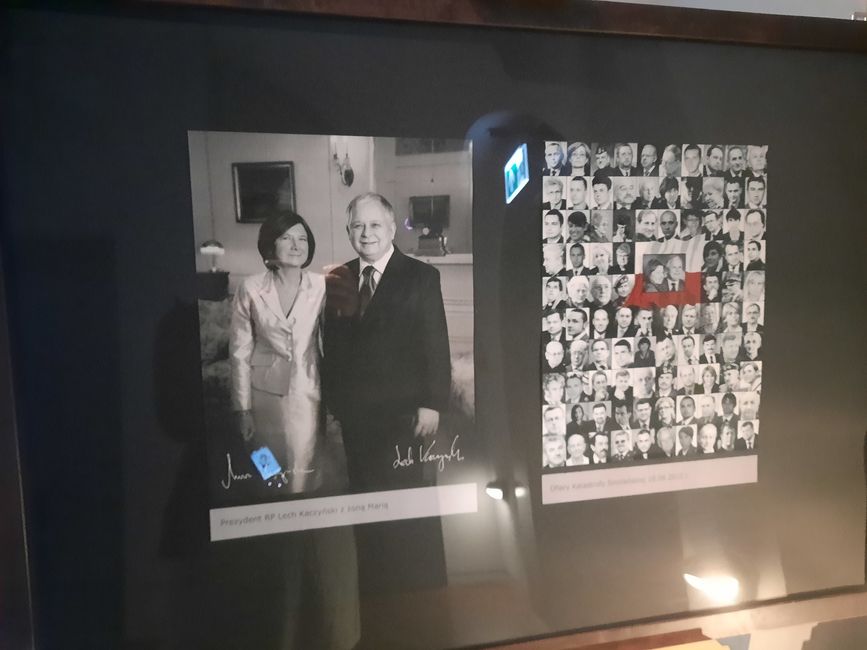

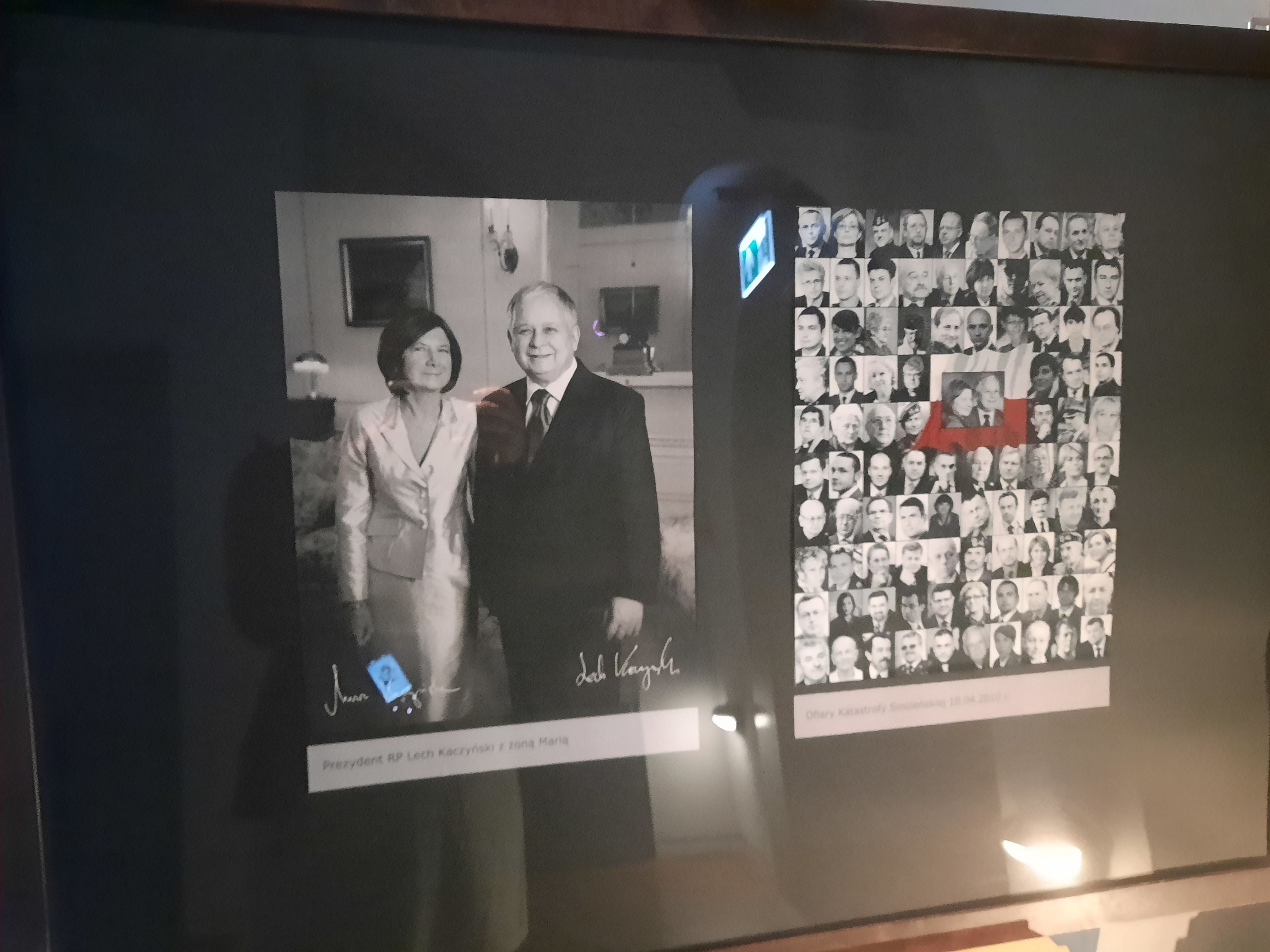

In 2010, Katyń and the crimes committed there in 1940 became more widely known in the Western media: now through the Smolensk disaster. The government plane, and thus Polish President Lech Kaczyński and the entire Polish delegation traveling to Katyń for the 70th anniversary, crashed. There were no survivors. A state of emergency prevailed in Poland. To this day, there are memorial services in Poland for these victims as well. Rumors persist: it is said that the plane crash was also a murder by the Russians. Putin as the central mastermind - and, according to the conspiracy theory, in close collaboration with Donald Tusk, the political opponent of the right-wing conservatives and thus also of the Kaczyński brothers. Some linked this tragedy of Smolensk with the Soviet mass executions of Polish soldiers and another plane crash: that of Władysław Sikorski, the then Prime Minister in exile, in 1943 over Gibraltar. The Polish story, so the narrative goes, is a succession of tragedies, martyrdom, and (heroic) struggle for Polish independence. There is surprisingly little to be found in the museum itself regarding the plane crash of 2010.

The museum is an excellent starting point to engage with the history of World War II from a different, non-Western perspective. Go see it!

PS: Other museums include (not in order): the Polin, the Warsaw City Museum, the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, and probably in the future, as it is currently also being developed, the Museum of the Warsaw Ghetto. The city has a great vibe and is brimming with change and future, whether in the Old Town, between skyscrapers, in parks, or by the Vistula. If someone asks me how long one should stay in the Polish capital, my answer is clear: a long time. There's much to discover! And if one has had enough of museums and stories, the Old Town and Nowy Świat are nice (and touristy), but much more beautiful around Plac Konstytucji and Plac Zbawiciela or simply by the Vistula!

Tsarisa eka Xiphephana xa Mahungu

Nhlamulo

Swiviko swa maendzo Poland