Traveling the world: seeing, imagining, tasting, selecting ... (Warning: only for people who also read longer texts)

Publicado: 01.03.2019

Willakuy qillqaman qillqakuy

Sorry. It got long, but how can you summarize six months even shorter?

In order to really travel the world, we have of course seen too little of it, but the long journey through 14 countries has still opened up an incredible variety to us: not only in the artworks that we all could visit as planned (really all - you can tell I'm proud, right?), but also in terms of standard of living and lifestyle, food and drink, landscape and climate, appearance and clothing, efficiency and failure in everyday life, propriety and politeness, and of course in dealing with the mass phenomenon of tourism and the many travelers. This may sound terribly dry in summary, but it is precisely this diversity - the new and foreign in each country, and (not always positive) surprises - that made the journey exciting throughout and forms the core of what I take home with me. And it confirms me in a basic attitude that my study of history brought me: everything that seems natural and immutable to us is only so in our living environment and at a certain point in time. Elsewhere, things are different and seemingly immutable, and a decade or even a century ago, life here and there looked completely different. What is important to me about this realization: nothing is fixed - and it is worth fighting for change.

Okay, enough of the pseudo-philosophical generalities. Here I want to summarize a few memories that come to mind spontaneously and give something to those readers who are also reading the final post of this blog: the secret of how to truly select a world journey.

I have already written a lot about the sights. So just briefly: The big positive surprises were Bagan in Myanmar and Easter Island (we would go back there anytime), the Mayan sites couldn't compete with our expectations. Overall, the buildings in Asia (Myanmar, Cambodia, India) convinced us much more than those in Central America.

We would not recommend the Seychelles: The beautiful and unique landscape cannot compensate for the fact that you cannot swim at any of the beaches there (either too shallow or too dangerous currents), that the locals are mostly rude and condescending to the point of rudeness, that the stay is crazy expensive, and that the food in restaurants and even the ingredients for cooking yourself are generally inedible. So only suitable for rich, thin, masochistic snorkelers.

With one exception, all our destination countries are much, much poorer than Austria. The richer country, namely Australia, is doing much better economically. And you can particularly notice this (we were only there) in Sydney. We have never experienced a city where the wealth of so many of its residents is so tangible. Sydney is a beautiful and livable city, expensive and incredibly friendly. It was a pleasure to be there, and very pleasant to live there for a very short time (five days) as we did, even better than at home. We would go back to Sydney anytime, even though there is nothing left for us to visit.

The reason I have avoided the countries we have now visited is also because as a tourist from prosperous Austria, I simply feared the daily confrontation with poverty in a form that does not exist here (anymore). For this trip, I adopted the concept of professional distance and used a scientific approach. And so the Human Development Index (HDI), which takes into account not only gross national product per capita but also life expectancy and education, accompanied us on our journey to assess wealth or poverty in a country.

Of all the countries we visited, Cambodia and Myanmar are the worst off. They rank 146th and 148th out of a total of 183 countries ranked. For comparison: Australia ranks 3rd and Austria ranks 20th. Next on the list is Chile (44), whose classification is not very meaningful for the remote Easter Island, which is poorly treated by the motherland. Then come (thanks to tourism) the Seychelles (62) and Georgia (70). The fact that Georgia is 50 places behind Austria was particularly understandable to us, as it looks very European there and therefore familiar to us. An 'impoverished' Austria would look about the same as Georgia does today. That's why - at least I think so - we found Georgia sometimes (e.g. in Kutaisi) so particularly depressing, even though we knew that people in Guatemala (127), India (130) or Honduras (133) would be licking their fingers if they could live there like the Georgians. The numbers don't always reflect our personal impression: Mexico (74) appears much more miserable compared to Thailand (83) or Uzbekistan (105), and by no means richer than Colombia (90) or Belize (106).

But all the distancing numbers don't help: people who wash themselves and their laundry in the river (seen in Myanmar and Guatemala) or tiny braided or wooden buildings (Myanmar, Cambodia, Belize, Guatemala, Colombia), no matter how pretty, tidy, and colorful they may be, are not idyllic and exotic, but signs of very simple living conditions. Not to mention corrugated iron huts (all too often), windowless wooden sheds and damp old buildings (both in India), tiny concrete shell structures (Mexico), or even the homeless in Delhi and Yangon. In short: in all countries except Australia, we have lived significantly better than the average locals. Hotel and restaurant employees, cashiers and ticket collectors at the sites - almost everyone we dealt with had a lower standard of living than us on the trip. This difference becomes even greater when we compare our life in Vienna. Maybe this has gotten too long now. But it is important for me, in the face of the great things you can see, not to forget how the country and its people are doing.

By the way, the mood in the country, how happy and friendly the people are, has little to do with the degree of poverty. In Georgia, Uzbekistan, India, Myanmar, Colombia, and Belize, people were always kind and helpful, sometimes even warm or exuberantly happy. I have the impression that a country's history plays an important role in its mood. Almost all the countries we visited were once European colonies: the most terrible legacy was probably left by Catholic Spain with its brutal and narrow-minded annihilation of every 'pagan' culture, including its carriers, followed by targeted dehumanization and economic exploitation of the remaining indigenous people. Belize is a special case: It had both Spain (only briefly) and England (much longer) as colonial rulers. The strict Spaniards are hated there, and the liberal English are appreciated. But even the English had a racist view of the people of their empire (as my reading recommendations below make clear), and they did not treat all colonies equally. The same also applies to the French, and regardless of the colonial power, the consequences continue to this day: where no investment was made, no infrastructure was built, and the local population was not offered education or even participation, the political and economic conditions remained precarious even after the countries gained independence - and often still are to this day: for example, in Myanmar (formerly British Burma), Cambodia (formerly French), and all former Spanish colonies. The neighboring colonies that received more support from England or France are much more stable: India, Vietnam, or Belize.

Therefore, the - let's say - collective psychological impairment in Cambodia and Guatemala, where unimaginably cruel systems had control until recently, is understandable. On the other hand, Myanmar is puzzling, which has endured many years of harsh military dictatorship and is not by any means a nice democracy today, although travelers don't notice this (at least until they venture into the areas of persecuted minorities). Mexico is also puzzling, despite its oil reserves, relative wealth, and long independence (since 1821), it simply appears depressed.

And now for something completely different: I didn't realize how varied the styles of clothing and body size of our hosts would be. In India, there were many beautiful saris alongside jeans and t-shirts, extremely well-nourished (mostly also wealthy) people alongside emaciated ones. On the Seychelles, muscular Rastafarians were a minority alongside plump people of both genders. People were nowhere as small, slim, and delicate as in Burma. Coming from Cambodia, where men and women are very thin and wear dark, long pants and skirts, the first thing that struck me in the subway in Sydney was: The people here are exceptionally well-nourished and wear very little fabric on their bodies. Then came my surprise on Easter Island: The tourists there mainly come from Chile, where people apparently like to eat a lot and limit their clothing to a minimal level of decency (regardless of body size and age). The enjoyable refusal to submit to the BMI terror continued in Latin America, but the openness disappeared from Guatemala. Traditional indigenous costumes were only worn there, and sometimes in Mexico, but it seemed more for us tourists (that was my impression). Belize was the cheerful foreign body in Central America: more Rastafarians and pure casualness.

By the way, a Western woman can survive for six months with six pants, two skirts, eleven t-shirts, one beach dress, two sweaters, two pairs of barefoot shoes, and one pair of sandals (as a luxury) - without dyeing her hair once and without even a little bit of makeup. And feels very comfortable doing so.

A Western woman can also survive six months without sports, but not without damage in the long run. Climbing temples and pyramids, long visits, and a bit of gymnastics are no substitute for swimming and intensive walking with my MBT shoes. All the beautiful muscles disappear, which leads to the figure melting away (after all, I'm not 20 anymore). A very unpleasant side effect of the lower muscle mass: women gain weight more quickly when eating.

And with that, we come to one of our central travel contents: food. And here, once again, we have one of our famous rankings:

India clearly wins on all fronts. A delightful, varied, and interesting cuisine, and we have eaten really well with two exceptions, so high restaurant quality as well. The variety of bread is remarkable, the rice is good - not everything, but most of it is spicy.

Rapa Nui comes in second place: my oh my, they have fish and seafood (slipper lobster!!!) of a quality that will make your ears stand up. And they can cook too. Ceviche can be soooo good.

Third place goes to Georgia. The cuisine is more down-to-earth, not as sophisticated as the Indian, not nearly as diverse, but the dishes are tasty and fun, the preparation was wonderful almost everywhere, and the portions were hardly manageable.

Myanmar follows with a completely independent cuisine, with salads standing out: for example, with fermented tea leaves and almost always with lots of peanuts. The main dishes are curries (fish, meat, and vegetarian), which are always served with rice, an intense, good clear soup as a 'side dish,' and a palette of bowls with pickled or cooked vegetables. Even at the simplest roadside stands, they are usually a delight.

Although it landed in a good fifth place, Thailand was still the big culinary disappointment. The culprit is Mrs. Sri Gumpoldsberger from the 3rd district, who cooks so well. Not many of the chefs and cooks who remained in Thailand could keep up with her. Usually, the much-praised street food is uninteresting to bad. An outstanding exception was the weekend night market in Chiang Mai. After all, Thailand also produced the best single meal of the trip: magnificent, huge river shrimp in a luxury restaurant in Ayutthaya.

I would like to spread the cloak of silence over the culinary delights of Latin America - and quickly forget about them. Yes, yes, we also ate well there, but so rarely that the fingers of one hand are enough to count the pleasant places.

New ranking, this time fruit: We were infinitely looking forward to the exotic fruits - and found them in Thailand in an incomparable quality and intoxicating variety, both for eating and as freshly squeezed juices. Second place goes to Georgia. Not exotic, but of breathtaking quality were plums, peaches, honeydew melons, and especially apples. Unfortunately, we were too early for the famous persimmons and could only taste one variety. Belize wins bronze because there, too, there are many types of fruit to discover, and it is good (we love zapote). India would certainly have been a hot tip, but there we were too afraid to eat fruit, but at least we dared to drink the lime juices (with sugar and salt) pressed at the roadside under dubious hygienic conditions - and that was an excellent idea. The Indian limes were by far the best of the trip. Everything else was comparatively bland because it was not new to us. Okay, the small bananas were good almost everywhere (at least when you let them ripen), guavas can be great, the quality of the pineapples was consistently wonderful, and mangoes can be a lot of fun, but why do they always and everywhere serve only watermelon, cantaloupe melon, papaya, and/or pineapple for breakfast?

Alcoholic beverages were not common: wine is only important in Georgia, and it can be excellent there. An interesting one is initially for all who adhere to modern orange wine, as its roots lie there: The Qvevri wines (called amphora wines in Europe) are not allowed to be imported into the European Union, which is a shame, I think. But even the classically aged wines are worth a trip to Georgia. When it comes to high-proof drinks, no country can even come close to matching the rum from Guatemala (Zacapa and Botran), the supposedly good Honduran brother Flor de Caña is quite weak in comparison.

I didn't want to believe it, but in Latin America, the coffee is really not good. We were in famous coffee-producing countries like Guatemala and Colombia - but no. Apparently, all the good stuff is exported. The best and most interesting coffee of all our destination countries was - unbelievably, but true - produced in Cambodia. We bought it too (it accompanied us and saved us for many weeks). BUT we discovered the probably best coffee of our lives (even though we know so many good Italian coffees) in Ethiopia, which we bought at a stopover at Addis Ababa airport. Does anyone know a stewardess or pilot from Ethiopian Airlines? Please contact us urgently.

It is unusual for the three meals we eat daily to be as clearly different from each other as they are with us. I have learned this. In almost all our target countries, the menu was the same at all times of the day (even in European-influenced Georgia). I found this quite monotonous during longer stays and now appreciate my breakfast sweet bread with jam even more than before.

I have never eaten insects before this trip and have learned to appreciate them. They are often a taste enrichment (ants), sometimes bland (grasshoppers), sometimes a bit strong in flavor (worms), but never disgusting. Really not!

And now for the grand finale:

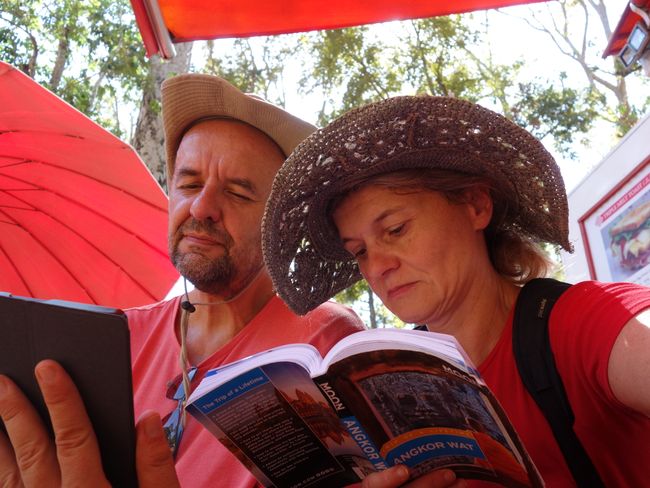

Reading is simply part of our travels (and planning). So we set off with 15 travel guides in our luggage, most of which we discarded because they did not prove themselves in practice on-site. A refreshing exception and highly recommended: Archeological Mexico by Andrew Coe (definitely buy it, even if it can only be purchased online in the USA). When planning our trip and now also when visiting the sights, the internet is a true blessing. And so for some destinations for which the travel guides did not provide sufficient information, we created our own guides from internet sources and took them with us on the e-book reader to the sights. The title photo shows us at work in the Bayon Temple in Angkor.

But I actually wanted to tell a different story. For the long evenings (when everything is asleep except us by 8 pm at the latest), the long waiting times (e.g. for the next flight) or the bus or flight distances, I had planned an accompanying program for the journey: to read at least one book by an author closely linked to each country. Fiction takes precedence, but as there is not literature in our sense everywhere, there were also non-fiction books (which I had put aside because reading scientific literature is usually my daily bread). Maybe my reading list contains one or the other tip for you too:

Georgia (I had a lot of time here, and there are also quite a few e-books in German, maybe because Georgia was the focus country of the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2018)

Boris Akunin: Fandorin (the first crime novel in a whole series, set in 19th century Moscow; Fandorin is the detective, Akunin is the pseudonym of a Georgian who is a big deal in Russia; it didn't convince me in terms of language or story, a bit too exaggerated, mannered, unlikely, and predictable)

Techno of the Jaguars. New Female Writers from Georgia (collection of short stories by contemporary female authors, including superstar Nino Haratischwili; mixed bag, as is often the case with such anthologies, but a good introduction)

Georgia. A Literary Journey (Here we meet Nino Haratischwili again, who had the brilliant idea to form literary duos that would travel a region of Georgia together for about a week and then write a short text about it. What makes it so interesting and nice is that one part of each team came from Germany, the other from Georgia. An urgent recommendation for anyone planning to go to Georgia.)

Archil Kikodze: The Story of a Bird and a Man (In my opinion, Kikodze wrote the best text for the 'Literary Journey', and I also found his novel to be excellent.)

Abo Iaschaghaschwili: Royal Mary. A Murder in Tbilisi (I chose this crime novel based on the 'Literary Journey' - it wasn't a good idea. It was a failure on all counts, a copy of the Akunin books set in Tbilisi.)

Uzbekistan (The first of several countries where literature in our sense is not a tradition, so there are very few novels, short stories, etc., and if there are, hardly any translations into English or even German.)

A Collection of Uzbek Stories (A collection of short stories translated and published in the United States on private initiative. Peculiar erratic plot developments that I couldn't make much of.)

Seychelles (No native authors in English or German, so I had to rely on an English immigrant who came to one of the islands with a member of the Persian Shah family after the takeover of Iran by the mullahs.)

Glynn Burridge: Voices. Short Stories from the Seychelles (Not great literature, but entertaining to read. Some things help to understand the islands better.)

India (Here, I chose a classic, Nehru's alleged favorite book.)

Rudyard Kipling: Kim (My first Kipling, and I am thrilled: great language, differentiated criticism of colonialism, and competent description of British India at the time. Kipling was also born in Bombay.)

Myanmar (And another classic that is now offered by street vendors at the temples, also in German, French, Spanish, or Italian translation.)

George Orwell: Burmese Days (Orwell, like Kipling, was born in British India, more precisely in Lahore, and worked in Burma. He clearly learned to hate the British as colonial rulers during his time there. The book is unreservedly critical, a bit heavy-handed in every way, but entertaining and quite worth reading.)

Thailand

Kukrit Pramoj: Four Reigns (Pramoj came from a political family and was an avowed royalist, which you should know when you take on the extensive family history. Biased and detail-loving and therefore also tedious, the novel describes the life of a noblewoman who experiences four kings and much social change. Not a masterpiece, but well suited for a long vacation in Thailand.)

Cambodia (If you look for a book from or about Cambodia, you usually only find literature about the time of the Khmer Rouge, often the reports of survivors of this terrible regime.)

Rithy Panh: The Elimination (Rithy Panh also survived the Khmer Rouge as a teenager. Later, he made internationally acclaimed documentaries about this time and studied the files from the notorious S-21 torture prison and interviewed its former director for hours. He presents himself alternately as a eyewitness and an expert. A depressing and informative book, sometimes a bit confusing and not always linguistically convincing.)

Australia: Patrick White - The Eye of the Storm (is still waiting at home, five days were too short for this thick book.)

Colombia (Here, there are many that interested me: Juan Rulfo, Octavio Paz, or Carlos Fuentes, for example, but hardly believable, here too, the e-books are completely missing or they are only available in English. And actually, I find it suboptimal when I get a book that I have to read in translation anyway (because I don't know enough Spanish) only in another foreign language. So it became a crime novel, and what a one it was.)

Paco Ignacio Taibo II: Four Hands (Here I found a new favorite book and an author I still have to read a lot of. Hopefully his other books are just as wise, funny, politically engaged, and artistically structured. Taibo has an infinitely large treasure trove of knowledge to draw on. US intelligence agencies, Stalinist purges, practices at universities and in the big drug business in Mexico, the Spanish Civil War, and much more are mixed together in the very best way. All of them observed with a keen eye, and portrayed mercilessly accurately. A heartfelt recommendation.)

Willakuy qillqaman qillqakuy

Kutichiy