From the Illawarra Polish Museum in Wollongong. Or better: From Zu-Falls

ที่ตีพิมพ์: 29.11.2023

สมัครรับจดหมายข่าว

Andrew is someone who gets straight to the point, to the actual topic, without further ado. So we are in the Polish center in Wollongong, just over an hour south of Sydney, in direct conversation without any small talk. He leads me quickly through the event hall and rooms directly into the museum.

I have the impression that we have known each other for a long time - but that is only half true and not really true at all. We've only known each other from a few Facebook messages and emails since the end of 2021. I don't feel like we've never met in person. It seems to me like we're continuing a conversation we started a long time ago; like meeting someone you haven't spoken to in decades. Above all there is a great warmth and enthusiasm for talking to each other.

The Illawarra Polish Museum , the Illawarra region's Polish museum, is actually just one room in the Polish Center and was opened by Andrew in 2016. He collects everything he finds - or is given to him - about Poles in the region around Wollongong. “Look, I didn’t want to take this children’s chair at first.” A small chair, more of a stool. You might think it belongs in the trash. He almost went there too. What was he supposed to do with it? A children's chair, made of wood, a bit of metal.

And then the owner came with a photo: of herself as a young girl in a dress, surrounded by other children, in one of the immigration hostels in Australia, shortly after emigrating. The children's chair was always there. “Now there’s a real story to it,” Andrew’s eyes sparkle.

These immigration hostels were a pivotal experience for all immigrants in Australia after the Second World War. They were the first place to arrive Down Under. Although they were again in collective accommodation like in the DP camps in Europe, they were still one step further. They had a visa, had completed the crossing, were in Australia and trying to start a new life. Andrew is looking for such objects, for objects with a story(s) - or better: finds them, maybe they will also find him and his museum. A question of perspective.

Poland in Australia didn't just start after the Second World War, he reminds us. In any case: the highest mountain on the Australian continent is named after the Polish freedom fighter and national hero Kościuszko - who here, however, is not pronounced in Polish (roughly) “Koschiuschko”, but in English-Australian and rather “Kosiosko”. You won't get very far in Australia with the (correct) Polish pronunciation. Almost no one here knows the “Koschiuschko” mountain. The first climber and namesake of the over 2200 meter high mountain - very roughly between Sydney and Melbourne - Paweł Edmund Strzelecki, has also lost his Polish pronunciation and thus the “ł”, “rz” and “c” in the Australian context. Poles came Down Under early on as colonists and saw themselves as pioneers. That is also part of it, but is often forgotten, says Andrew. He took some time after retirement and has been collecting the Polish-Australian past ever since. He actually wanted to study history after school, he tells me, but everyone asked him what he wanted to do with it after university. He was unsettled at the time.

And became a sailor. He therefore traveled professionally not in time, but in space. He proudly tells me that as a young man he was in over 100 countries thanks to his job. He worked for very well-known and rich Americans and came to Australia from socialist Poland in the early 1980s through many stops and detours. During the Cold War, at the time of martial law and the Solidarity trade union and thus before 1989, he was able to bring 50 (!) of his family members to Australia. Today he has almost no relatives left in Poland. Almost everyone is here in Australia. “If I had known that everything would change in the foreseeable future, I would probably be in Poland today,” he says, I get the impression a little wistfully. “I am Polish, I still think in Polish, dream in Polish.” His wife Elisabeth, Ella, sees it and feels it completely differently. She feels very comfortable in Australia, in Wollongong. She is sure that she would no longer live in Poland. “Not even just political,” she notes. Both Andrew and Ella had been seriously ill on several occasions. “Something like that in Poland back then. No chance." Australia, the medical care here, saved their lives and also gave them completely new opportunities. They now have Australian citizenship. Since they can no longer travel anyway, the Polish passport doesn't play a big role for them. However, Andrew would still describe himself as Polish, of course. That's why he is so active in Polish society here in Wollongong.

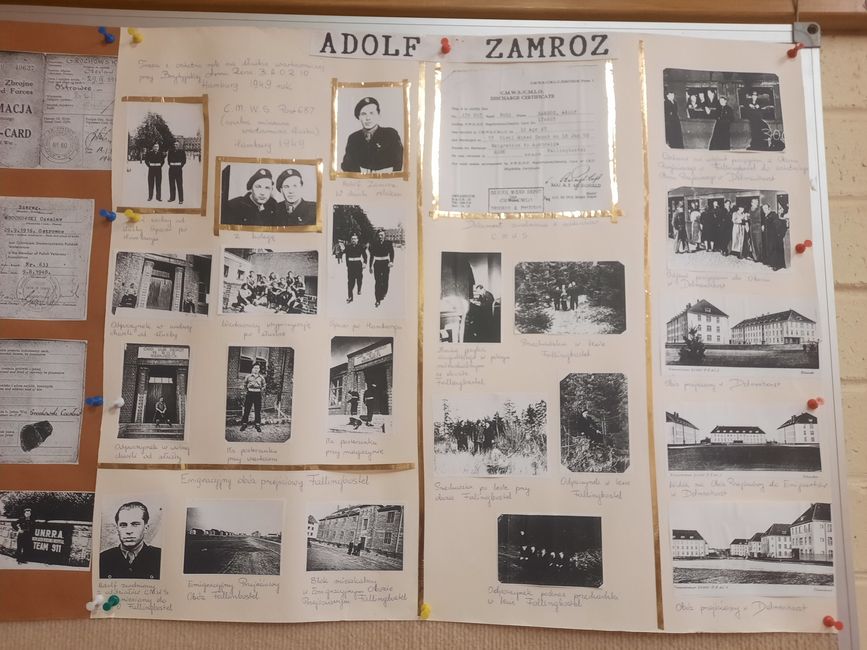

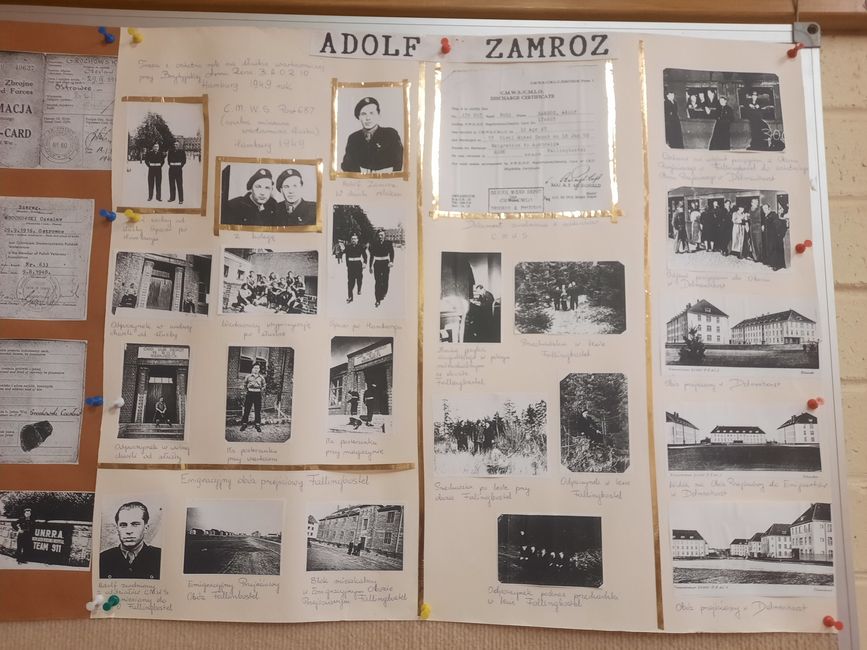

Andrew is full of enthusiasm and proudly shows off his collection and museum. I'm impressed with what he's put together and how well he's archived it. I know this to be very different from smaller museums and archives that rely on voluntary work. “I am not a historian or archivist. I didn't learn that. But I asked around how to do it that way. Look here, all objects have a number. I write down the sources and the origin of the information; I printed out the explanations once and then digitally at home. And here I have compiled all the immigration lists for Poles who came to the region. And look here, here I started a collection by family name. And there, that's the person you're interested in. He was very well known here and led our choir. My wife was in the music group with him.”

When Andrew first started his search he went to cemeteries in Wollongong and looked for graves that had Polish inscriptions. “Very basic”, very simple. This was his starting point. More is known about Polish emigration after the Second World War and there are also more documents. For him it is important to also tell the story of what came before. Such and such a person was important in the region, started or built this and that “and of Polish origin”. “And then made the name more English or changed the name. (...) And look here, these are families with Polish-Jewish heritage and this one has a more German-sounding last name, but lived in Warsaw until he came to Australia.”

Andrew is now constantly receiving requests for family research from people from here, from Australia with Polish ancestors, but now also from Poland. His Facebook page helps with that and that's also how I found Andrew and the Polish Museum. In recent years he has even helped families from Australia to reunite with those in Poland or to get to know them for the first time. Successes in his work that obviously make him very happy.

Photos from before emigration, from Polish DPs in Germany, photos from the time in Nissen huts and immigration hostels. From the 1940s onwards, if DPs received a visa for Australia, they had to commit to a two-year contract with the Australian state. This usually involved hard physical work in places that were considered unattractive for Australians. In the outback, on sugar cane plantations, in mines; often separated from family members, far away, often in absolute heat, somewhere in the middle of nowhere. The Australian state saw the immigrants and former DPs as workers; what they had previously experienced and had to experience in Europe and during times of war played no role. For the DPs, Australia was a chance to get away from Europe with a two-year work commitment and they accepted it, had to accept it, if they wanted to leave Europe. The alternative was to wait and endure further uncertainty for an indefinite period of time, without knowing where you would otherwise end up or what the conditions and requirements there would be.

What does someone take with them on a trip like this? To the other side of the world, back in the late 1940s? What ideas did they have about Australia before the crossing? Andrew shows me soldiers' badges, small trinkets and commemorative tokens created in the Pawiak Gestapo prison in Warsaw, documents, papers, photos. And he smiles: “Guess what someone brought with them!” He laughs and leads me into the small anteroom of the museum

and shows me a scythe.

“I took a closer look at it and had it checked. It is original and the scythe blade was made in Austria! Look, it’s there too.”

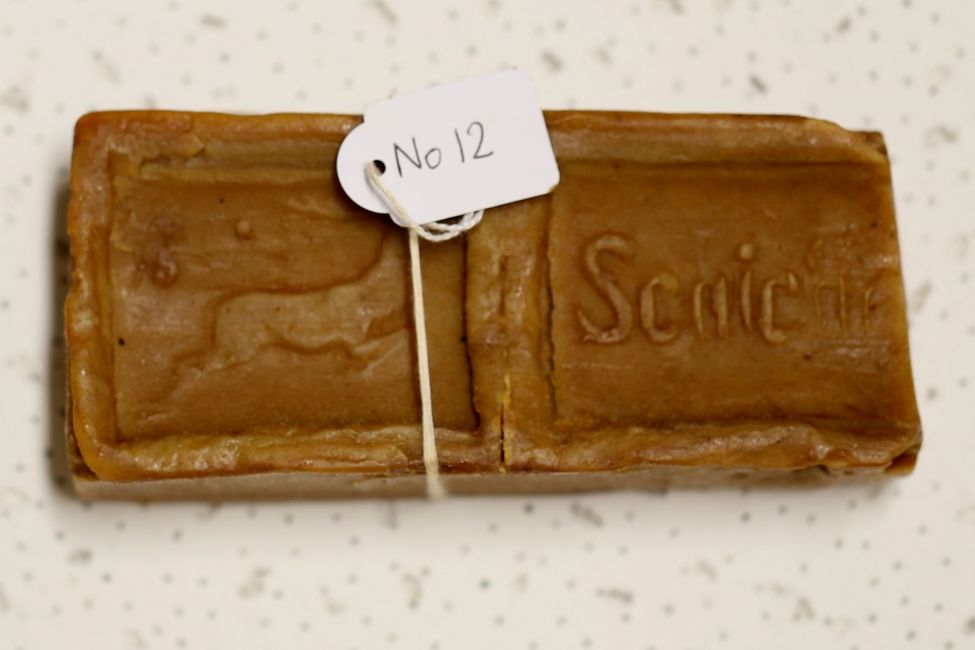

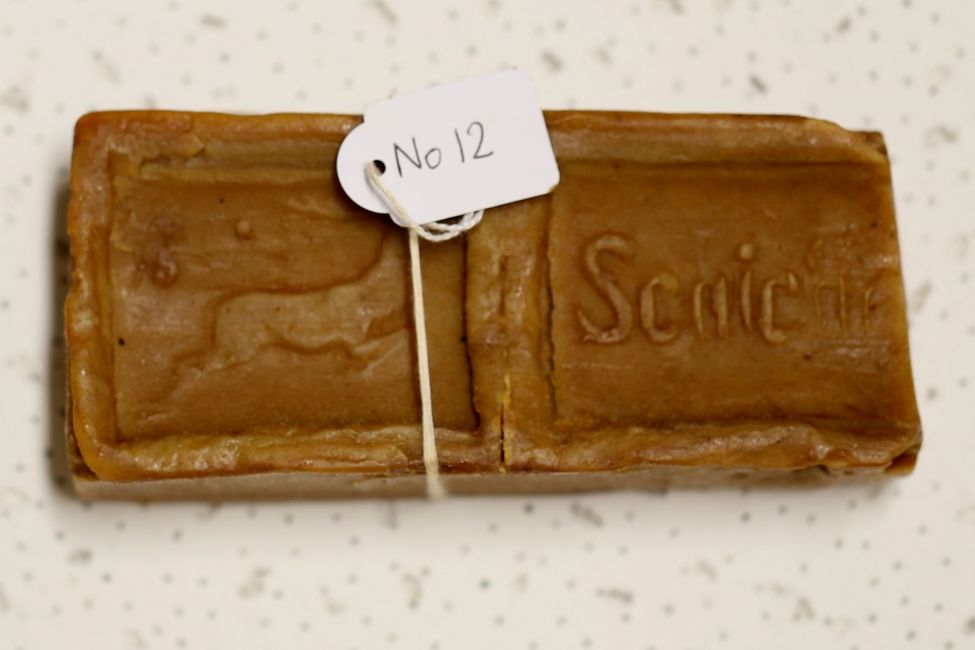

When a woman from socialist Poland married a Polish Australian, she also received a large bar of soap from her family. “Something like that is definitely hard to come by! There’s a lot of things that don’t exist in Australia!”

Collecting stories like this is his job, says Andrew. Enthusiasm radiates from him and he says this with a conviction and certainty that I believe him without question. He clearly sees that the Polish community is getting smaller and smaller. “We are dying out here.” The first large generation that built the Polish center, a bar and a large event space in the 1960s has long since died. At the annual general meeting, today, before our meeting, there were about 35 people there, previously there were over 600.

Many younger people and descendants now live in mixed families. Multiculturalism. That's good too. But Poland and Polishness no longer play as important a role as it did for their ancestors, as it did for the first generation that arrived here. There is still a classroom in the Polish center where some children learn Polish on Saturdays. But the atmosphere and mood here a few decades ago was very different, he remembers.

So Andrew collects stories because who else would and they are important, at least to him. It's his job. There are some members who are also history buffs and are currently recreating a Polish airplane model, so they meet once a week and have a common project. “Look, it even has a motor!” And he laughs. “Touch it! Looks like the real thing, but it's all plastic!

The museum does not receive any support from the Polish embassy. His relationship with it is complicated and so far it has worked without it. The site is large and worth a lot today; the house itself was built in the 1960s with the help of volunteers. It's there and even if there isn't a lot of money, it's enough for what they want to do.

Andrew lives for this museum, says his wife Elisabeth. He has always been busy with this since he retired. Since retirement, his life has been the life of the Polish community in the Illawarra. And then we change the subject.

Ella: “Where did you learn Polish?”

“Especially in Łódź and at the university,” I answer.

“Don’t you have Polish ancestors? Why does a German learn Polish!” - which was more of a statement than a question. She smiles.

“Yes, that’s right, a life’s work, definitely.” We laugh and I talk about my family history and what I know. The maximum connection that I can find family-wise to Poland, to Eastern Europe, is that part of my family originally comes from Lower Silesia, now Poland. “As far as I know, no one in my family spoke Polish.”

Then I add that I grew up in north-east Germany. Even though I was never interested in Poland as a child and teenager there, today it takes me less than 30 minutes to get to Szczecin from my parents' house. "Oh! How is the place called?!" Ella interjects enthusiastically. “We are from Szczecin!” she speaks quickly and positively excitedly: “Where are you from exactly? That's a coincidence! I definitely know that!”

“Um, Prenzlau is the next largest town.”

Ella laughs: “Of course, I know that! I went shopping there in the 1970s!” She laughs again: “What a coincidence! And what was the name of the other place again? Exactly, Neubrandenburg! I often went shopping there!”

I'm perplexed and have to smile. Crazy.

Andrew remembers the highway, concrete slabs and that sound when driving: bubboom, bubboom. Bubboom, bubboom. “Do they still exist?” Now I have to laugh! “No, not that, but I remember that too. If you took the highway to Prenzlau, you drove past my parents' house and through my village." Crazy!

There we are in the Polish Museum in Wollongong, Australia, with the Pacific on our doorstep and all from the same region, 30 minutes apart. But - and to make it even crazier - that's not why I'm here. I contacted Andrew because I was writing my doctoral thesis about a place in the Bavarian province and one of these people was active as a choir director in the Polish house where we are standing here in Wollongong. Coincidence is no longer sufficient to describe the situation. Coincidence sounds too religious, even esoteric, but the Duden tells me that it is an apt synonym for “coincidence”.

Two days earlier I had been invited to a workshop at ANU, the university in Canberra. Since my arrival in Sydney about eight weeks ago, my roommate has been saying that I should definitely meet Kasia, the Polish scientist at ANU. They often worked together and were a great exchange and conversation partner. Kasia quickly invited me to a workshop. I gave a lecture. In the evening over a glass of wine, we talk about this and that and she casually mentions that before Australia she worked at the university in Łódź.

“Which faculty?” I interject.

“International and political studies.” - “Crazy, Kasia!! That’s where I did my semester abroad!” I blurt out and am flabbergasted.

She: “I was there until 2011/12 and then on parental leave. When were you there?”

“Winter semester 2011/12” .

We were in the same building! Maybe we've met before. Again and again: crazy!

“Chance” in English: coincidence. The German translation of a meaning would be something like: “a remarkable coincidence of events or circumstances without an obvious causal connection”. A physical explanation is that ionized particles or other objects are present in two or more detectors at the same time or from two or more signals at the same time in a circuit. Who knows which of all this is true. In any case, it is more than usual; both meetings, the one with Kasia and the one with Andrew and Ella. And I notice that such coincidences or, according to Duden, “favor” or “lucky circumstances” mainly happen when traveling - or that I become particularly aware of them there. And I can't find any rational explanations for many of these encounters and overlaps, and they make me wonder: how did this come about? How did this (become) possible? Sometimes it seems things just fall into place, somehow and just like that, out of an unexpected complete void.

So it might be. I had a fantastic visit to the Polish Museum - as well as in Canberra -, great conversations and if everything works out, I will give a talk next year for the Polish community and the much larger and newly founded Migration Heritage Project in Wollongong. This was certainly not the last visit to the region and who knows what unexpected overlaps there will still be. I am and remain full of joy of discovery.

สมัครรับจดหมายข่าว

คำตอบ

รายงานการเดินทาง ออสเตรเลีย