Mexico: San Cristobal de las Casas

La daabacay: 28.01.2018

Ku biir Wargeysyada

From Palenque, we traveled another 8 hours into the Mexican hinterland to San Cristobal de las Casas, located in the state of Chiapas. Chiapas is the poorest state in Mexico, despite being rich in resources such as coffee, fruits, and amber. Many indigenous people live here, and it is also the stronghold of the Zapatista movement. Additionally, it is cold, very cold, at least in San Cristobal, which is situated at an altitude of nearly 2000 meters. The temperature was just a few degrees above zero. So we were glad that we had warm clothing with us, although it meant wearing the same things for the 6 days we stayed there. Chiapas is definitely the most authentic area in Mexico that we have visited, in stark contrast to the coastal towns of Cancun, Playa del Carmen, and Tulum.

Upon arrival, we went to the booked hostel. Unfortunately, the room we had booked was under renovation, and the alternative they offered did not meet our expectations (e.g., no private bathroom). Tired and exhausted from the long journey, the host could clearly sense our frustration. He was probably also relieved when we agreed to cancel the reservation without any charges and find another place to stay. That's how we ended up at Hostel 53, which turned out to be a stroke of luck because we met Alex there. Alex is from a small town further north in Mexico and has been traveling to all states of Mexico, working odd jobs and doing volunteer work. He was also working as a volunteer at Hostel 53, receiving food and accommodation in return. We had many interesting and exciting conversations with him during our time in San Cristobal and learned a lot about the real Mexico.

San Cristobal is famous for its beautiful churches and their extravagant interior decoration. Unfortunately, all the churches we wanted to visit were closed, which surprised us. Alex explained to us that this was due to the earthquakes a few months ago. Although not much damage was done, there is concern that the churches or parts of them could be at risk of collapse. Therefore, certain renovations are being carried out. So we could only admire the churches from the outside, each of them protected by a corrugated iron wall. Well, there are certainly more captivating photo opportunities.

We visited the Templo & Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo Guzman, where the museums "Museo de los Altos de Chiapas" and "Centro de Textiles del Mundo Maya" are located. The Museo de los Altos de Chiapas was entertaining but nothing special, focusing on the Spanish conquest of Latin American territories and the Catholic Inquisition. The Centro de Textiles showcases over 500 examples of handwoven textiles from all over Mexico and Central America. The exhibition starts with a very interesting film explaining the cultural significance of textiles for indigenous people and showing the different techniques of spinning, dyeing, and weaving. The rest of the exhibition does not provide much explanation, but you can simply admire the many different and colorful pieces of clothing. Traditionally, people wear huipiles, sleeveless shirts, for example.

We also "hiked" up the small Cerro de Guadalupe, or rather climbed a few stairs. At the top, there is a church that was actually open for a change. The view from up there is supposed to be wonderful, but it was nothing special. We couldn't see much of the city because it was surrounded by trees.

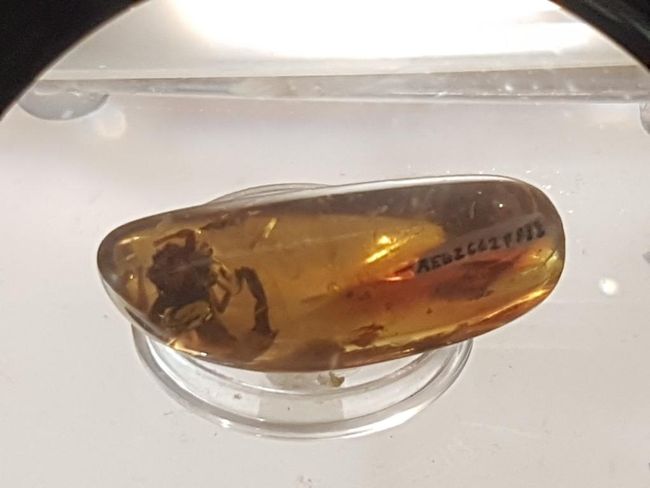

A must-see in San Cristobal is the Museo del Ambar (Amber Museum). Amber mining is very important in Chiapas. The museum shows an interesting film that illustrates how to distinguish real amber from fakes. It is very helpful if you plan to buy some jewelry as a souvenir. One characteristic of Chiapas amber is that it starts to glow green-blue under UV light. This property does not apply to amber from other regions of the world, as they are made from different resins. Amber is actually just fossilized resin (about 40 million years old). The film also shows how amber is cleaned, cut, and processed. There are also some display panels that provide information about amber mining. Amber with small preserved insects is especially valuable as it not only serves as a gemstone but also as evidence from bygone times and for research. Another specialty of Chiapas is red amber, which is primarily found in the outer areas of the mining areas due to more exposure to light. The exhibits in the museum mainly consist of special items, such as specially crafted jewelry, stones with insects, particularly large pieces, etc. The museum is worth a visit, but you can go through it relatively quickly. The museum director was present during our visit and approached us, mainly because of Jörg's noticeable height. He wanted a photo of us in the museum, and in return, he gave us a short private tour with some exclusive explanations. Win-win, I would say. 😊

Afterwards, we visited the Museo de Jade (Jade Museum). It's pretty much the same, just jade instead of amber. This museum is privately owned and therefore more focused on the sales area than on the actual exhibition. It was still quite interesting, with various exhibits showcasing the significance of jade for different indigenous peoples. There were also reproductions of various jade death masks found in the Maya ruins of the area. Unfortunately, we didn't learn much about the mining of the stone.

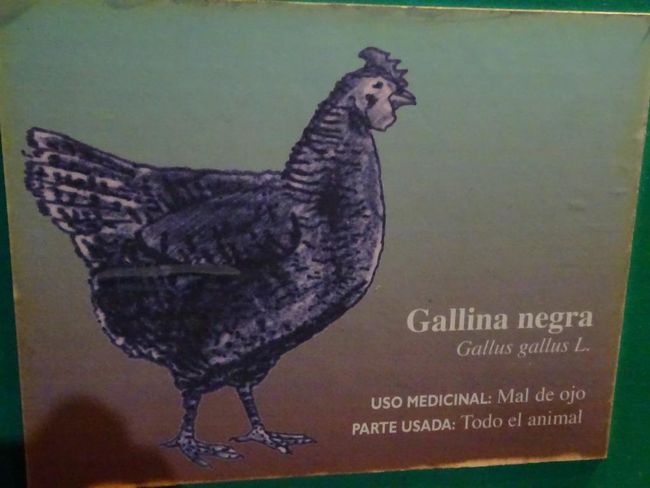

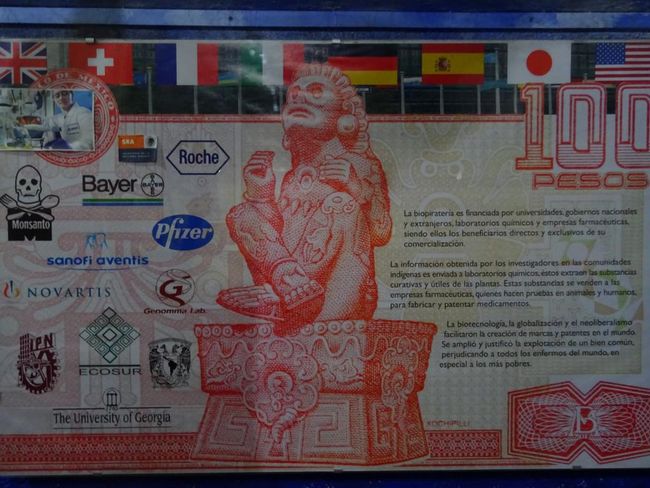

After a long walk through the city, we arrived at the Museo de la Medicina Maya (Museum of Mayan Medicine). The museum itself is quite small and not particularly well-made, but the topic is very interesting, and it was fascinating to read about Mayan healing methods. Among other things, it showed the process of giving birth. There was also a room that focused on biopiracy, with European pharmaceutical companies taking advantage of Mayan knowledge of plants and substances, patenting the resulting medications, and selling them for high prices. It is fair to say that these companies (including some well-known Swiss companies) did not simply take over and patent the knowledge (wild-growing plants cannot be patented), but also conducted research to utilize the active ingredients for medications. The Maya, on the other hand, advocate that knowledge of these ingredients should be freely accessible to all people. This is a beautiful idea, but unfortunately, in today's globalized and capitalist society, it may be difficult to implement. The museum also has a medicinal herb garden, a pharmacy (where we bought Maya medicine against mosquitoes, let's see if it works), and a Casa de Curacion, where people can receive medical treatment with Maya medicine. I actually considered getting my weak eye treated there (just for fun, it wouldn't hurt). However, I dismissed this thought when I read in the museum that for the treatment of eye diseases, a chicken, or rather all of its parts, is used. I really had no desire to witness them slaughtering a chicken.

The Museo de la Medicina Maya is located near a ring road that surrounds the city center of San Cristobal. Outside this ring are the poorer areas of San Cristobal, where mainly indigenous people live. And you can clearly notice this when walking to the museum. The further you get from the Central Park, the more dilapidated and run-down everything becomes. And that brings us to a central aspect of the experience in San Cristobal. It is noticeable even in the city center that there are far more beggars here than anywhere else we have been. There are even people lying on the street corners with wool blankets. And the beggars all wear traditional indigenous clothing. It was particularly striking when we were in a small 24-hour shop to buy a canister of water when suddenly something tugged at my pants. When I looked down, there was a little girl, maybe 5 or 6 years old, looking up at me with her brown eyes and begging me to buy her sweets. I generally don't give anything to begging children because I believe that begging should never be more rewarding than going to school. And I certainly wouldn't buy sweets for a hungry child. I wondered where the little girl lived, whether her family had a house, whether they had a kitchen to cook something. If there had been rice in the shop, I would have bought her a kilo of rice, but they only had cheap snacks, sweets, drinks, and cigarettes. It almost broke my heart, and I really struggled with myself, but in the end, I didn't buy anything for the little girl. A few days later, Jörg was in a Burger King and observed several of these children hanging around and begging. As soon as they had gathered some money again, they bought ice cream inside. Apparently, this happened repeatedly. It makes you wonder: Why would you buy ice cream at Burger King as the first thing when you're hungry?

We talked to Alex about this situation and wanted to know how he deals with it. He told us that many indigenous people live in small villages secluded from the cities, and only about 20% of the children attend school, with only 10% completing primary school. Apparently, primary school is the only compulsory education in Mexico, so many children drop out after primary school. While education itself is free in Mexico, there are still other costs associated with attending school (transportation, food, school uniform/clothing, school supplies, etc.), which many families cannot afford. This problem is exacerbated in indigenous communities for two additional reasons: 1. The government does not know how many children are living in the indigenous villages, making mandatory education difficult to enforce. 2. The children from indigenous communities largely do not speak Spanish at all. So they cannot simply be enrolled in school along with other children and learn the curriculum, as they would first need remedial instruction to catch up on the language disadvantage, but apparently, the government does not care about that.

As we mentioned earlier, Chiapas is the main region of the Zapatistas. They are a predominantly indigenous revolutionary group. The Zapatistas gained international attention in 1994 following the armed uprising of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional under Subcomandante Marcos. Since then, these people have been using political means to fight for the rights of indigenous people in Mexico, as well as against neoliberal economic policies and for autonomous self-governance. Alex told us that the Zapatistas live in villages around San Cristobal, and nobody knows who belongs to them because they always appear masked. They apparently even have their own university, the location of which is unknown to the general public. Alex believes that non-indigenous Mexicans can hardly or not be admitted to this university, unless they immerse themselves in this way of life for a long time and join the indigenous communities, so to speak. In this sense, the curriculum probably includes fewer classical, Western school subjects and more aspects of agriculture, indigenous culture, and their languages, etc. We also read in various museums that the indigenous people of Mexico still feel very robbed and deprived today, just as they did about 500 years ago during the Spanish conquest, and they put up a very accusatory fight against "Westernization."

And that, in my opinion, is the crux of the matter. As long as these people live in their villages and continue their way of life among themselves, there probably won't be any major problems. Of course, I also think it is important and valuable for people to preserve and continue their own culture and traditions! But as soon as these same people want to move to the city, own a smartphone, have internet, and other luxury goods, it becomes difficult. Since they have not learned anything that is useful in the globalized civilization (as harsh as that may sound), and they do not even speak the national language, they are pushed to the margins of society and live in poverty. And it cannot really be attributed to a lack of job opportunities in Mexico. There are job postings literally EVERYWHERE, in almost every store, restaurant, shop, in every city we have been to. Most of them do not even have high requirements, they simply seek "people who are used to work" or "people who can pitch in." We have been amazed at the abundance of job openings time and time again.

Alex also asked us a question that surprised me because I had never thought about it before: Are there indigenous people in Switzerland or Europe? Well, are there? Not really... actually, we are the indigenous peoples, most people here descend from the former Spanish, English, French, German, Dutch, etc. colonies. There are definitely no people living in secluded villages in the woods without electricity and running water. But we were the ones who went out to impose our values and way of life on others. And now there is no one who feels called to address the resulting social problems that have existed for centuries.

For our last day, we booked a tour to Simojovel, the amber mining area, to visit the amber mines. It was a long journey, about 3 hours, and at least we had a decent car since we were the only participants. On the way, we passed through many settlements and villages, and our driver told us that this is where the Zapatistas live. Twice, there was suddenly a roadblock in the middle of the road, with about 10 guys wielding machetes and demanding money to continue. Our driver tried halfheartedly to resist, but ended up paying anyway. If he hadn't done it, I would have, as these people did not look like they were up for any fundamental discussions. And they were only asking for a few pesos. At the second roadblock, an apparently slightly drunk guy stumbled around our car and looked inside the windows until his companions pulled him away. There are certainly more pleasant experiences than this.

Somehow, you can understand it. Every day, countless vehicles pass through their village, traders, and tourists, without them benefiting in any way. So they declare themselves autonomous communities that do not submit to the usual laws and customs and therefore demand tolls. So far, so good. But the whole thing becomes absurd when you hear complaints that the government does not take care of maintaining and repairing the roads here. Well... hardly surprising.

When we arrived in Simojovel, we immediately felt a strange vibe, and not just because we were the only foreigners there. We didn't feel safe there, it was probably the least safe place we have been to on our entire trip so far, and we were relieved to have come with an organized tour rather than on our own. In the city center, we met our guide, a young woman with a baby. Actually, every woman of marriageable age seemed to have 2-4 babies with her. So we were complete and set off to the mines.

From the parking lot, we had to walk about 1.5 km through the forest, and we passed small holes that turned out to be abandoned mines. Eventually, we reached the largest mine at the moment (meaning it was at least tall enough to crawl without being on all fours). There, we met some mine workers who took us inside. The guide and the driver stayed outside, and they probably knew why. So we walked several hundred meters (it's really hard to say exactly how far it was, it felt like an eternity) into the mine until we reached its end. And with every step, it got hotter, darker, stuffier. It was already hell for me to crouch and walk through the narrow passages, imagine what it was like for Jörg. And if I never had claustrophobia before, I definitely had it in there. There was hardly any air to breathe, sweat pouring down, it was just terrible. And at the end of the tunnel, we met the worker in the mine who was chipping away at rocks with a pickaxe. And he kept hitting... and hitting... and hitting... he does this for hours, days, years, his entire life. I could only stand it in there for about 10 minutes, but it felt like 10 hours. No, I would never trade my profession for this one. Just when we were there, he chipped off a piece of rock, and out fell: a little piece of amber. Jörg immediately made him an offer to buy it, after all, it was something special, right? We were there when this piece of resin was chipped out of the mountain after 40 million years. The worker was quite embarrassed and eventually mentioned a price (was it 2 francs?). Jörg doubled the price, anyway. When we passed by that mine again later, the colleagues were sitting outside in the sun and had apparently stopped working for the day, considering the exorbitant price we paid for the piece. Good for them. Normally, it is the guide and the driver who pocket the tip for the tour, but we wanted to give it to these people who work very hard and deserve a free afternoon in the sun.

Later, we talked to another group of mine workers, a father and his 4 sons. And the sons were definitely all minors, they were teenagers, almost children, running in and out of the mine. They asked our guide where we came from (they were apparently too shy to ask us directly). The guide said from Switzerland, and that it was a long flight, probably about 15 hours. The boy asked astonished how long it would take by car?! To that, I jokingly replied, imagine how long it would take to swim there! When he replied in halting Spanish, "Why, is there a river in between?" I realized that the poor boy probably hadn't spent many days in school.

90% of the people in Simojovel make a living from amber mining. The men work in the mines, and the women process the stones afterwards. Interestingly, it is actually the women among all these indigenous peoples who learn and develop actual artisanal skills that they can also use in other areas of life. Women can produce textiles, work with stones, make jewelry, etc. These are activities that are also in demand in the modern world. Girls learn these skills from their mothers from an early age. On the other hand, men seemingly cannot do anything (sorry, it sounds really harsh), yet they work so hard every day.

The mines are operated independently, with each family being allocated a piece of land, and they independently mine into the mountain, each on their own account and luck. All of this is done by hand! Blasting is not possible as it could destroy the fragile amber. Finding the stone is also not easy, there are no veins like with other stones where you can uncover a large amount once you have found the vein. It is really a matter of extreme luck, the miners told us that sometimes there are whole weeks where they simply find nothing. The only tool used is a pickaxe. That's it. The only industrial advancement this industry has seen in the last 200 years is the switch from candles to headlamps! And that is actually progress, as the battery-powered lamp does not consume additional oxygen and does not emit much heat. However, this unfortunately leads to empty batteries being scattered everywhere in the forest where the mines are located. Of course, we don't find that cool at all... but there is simply no battery bag or awareness for it here.

There are also no safety measures. No helmets, goggles, protective clothing, nothing. A few boots, pants, no T-shirt. The walls of the mine are not supported, loose rocks fall from the ceiling again and again when the worker hits the rock with the pickaxe. Imagine the nice Suva employee, he would probably have a heart attack at the sight of it. When you ask if there are many accidents, they say, "No, not really. Occasionally, yes." Well, that's a different perspective, they don't keep accident records here, there is no bonus-malus system for working 365 days accident-free. Occasionally, some workers are buried in accidents, it happened just last week, and then people from the village help each other recover the bodies, but they have to hurry because the air inside is scarce. Only during the rainy season, the mines are not operated as they quickly get flooded. I don't even want to know how many people have drowned in there during heavy sudden rains. Once, a huge snake sat at the entrance to the mine, one of the boys recounted. So they just waited inside the mine until the snake disappeared.

We left the mines with a strange feeling. It was an incredibly interesting trip, that's for sure. I have great respect for these people who earn their living in this way and support their families. Especially considering that they receive the least of what you pay for a piece of amber jewelry, despite doing the hardest work.

Afterward, we visited the local amber museum in Simojovel, where our guide gave us some additional explanations. However, nothing was as impressive as the feeling of being inside that mountain. Finally, we visited the local market on the central square, where some vendors offered amber jewelry. Of course, I couldn't resist buying a pair of earrings before we made the long journey back to San Cristobal.

This was our time in San Cristobal. I am writing this part of our blog now that we are already at the end of our time in Mexico, and I must say that San Cristobal and the Chiapas region were our favorite parts of Mexico (or the small part of Mexico that we have seen so far). Although we were also confronted with the unpleasant and problematic sides of the country, the experience was very authentic, and we learned and saw a lot here.

Ku biir Wargeysyada

Jawaab

Warbixinaha safarka Mexico