Who remembers Subcomandante Marcos?

ප්රකාශිතයි: 02.02.2019

පුවත් පත්රිකාවට දායක වන්න

I remember, and that's amazing enough, because the mysterious man with the cloth over his face, who became famous as the spokesperson for the indigenous uprising in the Mexican state of Chiapas, appeared in our newspapers and TV news in 1994. He did a good job, no doubt. Today, with the resources of Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, his success would probably be even greater. But he has stayed in my memory: maybe because he was something like a mix of Robin Hood and Zorro, because his true identity was not known for a long time.

Why am I telling this? We had three points of interest on our itinerary in Chiapas, which is now considered peaceful and safe. The latter is true based on our experience, but the resistance of the Zapatistas (the movement led by Subcomandante Marcos) from the 1990s is by no means dead. No wonder, the miserable living conditions of the indigenous people (in no other Mexican state is their percentage of the population higher than in Chiapas) still exist. For example, in a village near the tourist attraction of Palenque, we saw a large hand-painted sign indicating that we were in Zapatista rebel territory. And a few kilometers further, we suddenly encountered a roadblock: consisting of a log blocking a lane, a rope stretched across the road held by a man, and a 10-year-old boy who came to our car window with a Styrofoam cup and demanded 'colaboración'. What to do? When we helplessly said, 'No hablamos español', the child took pity and demanded 20 pesos (not even a whole euro). After paying the toll, the rope was lowered and we were allowed to continue. You can hardly imagine more humble 'highwaymen'.

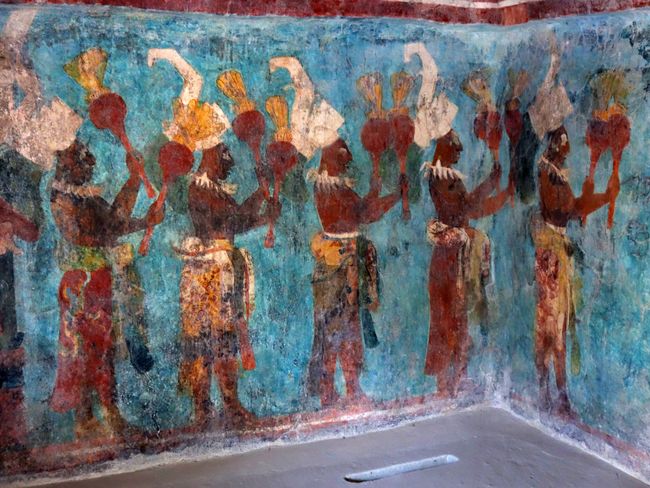

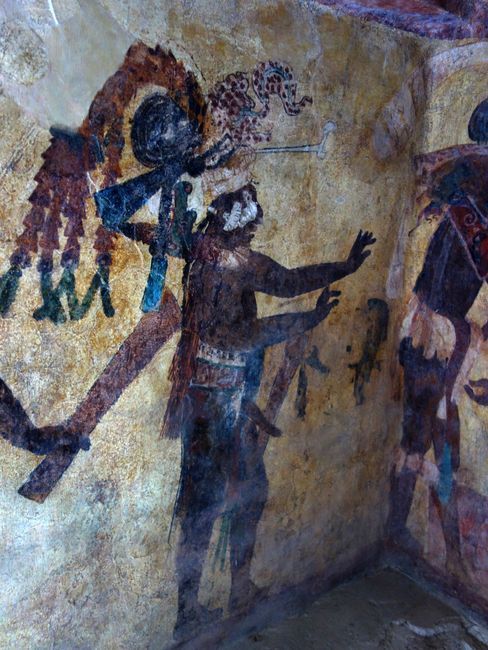

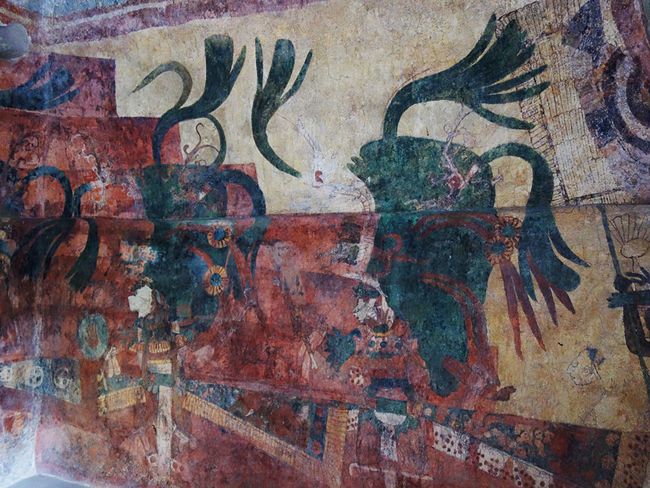

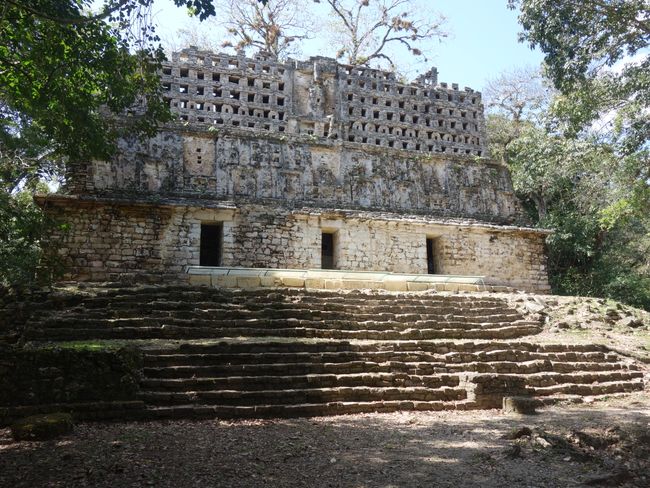

A bit of this humility would have done the indigenous people who control access to Yaxchilan, a Maya city in the middle of the jungle that can only be reached by a 40-minute boat ride on a river, some good. I was looking forward to the Lacandon people, who are said to be the most original - and therefore also the poorest - of all Maya peoples. Many of them really still live in the middle of the jungle, many kilometers from the nearest road. Not so those who monopolistically offer boat trips to Yaxchilan and operate the hotels and restaurants in the nearest town. They charge 55 euros for the boat trip, which is simply extortion considering the local price level (a large bowl of guacamole with nachos costs 1.40) - and blackmail, because what can you do if you have driven 2.5 hours on a bad road with many potholes specifically to get here? I have rarely seen people who do their work with so much obvious reluctance, like the waiters in our hotel restaurant. No, not all Lacandon people are like that. And I was able to indulge my tendency to pay slightly higher prices to support this people when visiting the magnificent Maya frescoes in Bonampak. There, too, we were forced to be transported by them to the archaeological site (this time by taxi), also at inflated prices (the ride cost twice as much as the entrance tickets) - but it didn't matter, it still wasn't much money. And the taxi driver, as well as the operators of our accommodation there, were kind, friendly, and cheerful.

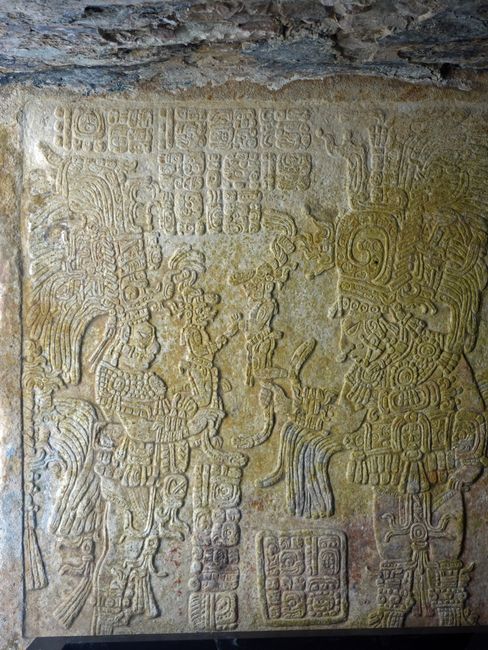

Finally, a few words about the Maya sites in Chiapas: Palenque, a medium-sized ancient city that our guidebooks rave about, we found underwhelming, but there are really great relief plaques and incense burners in the museum. At this point, I would like to refer to my favorite bespectacled Maya ruler from Copán in Honduras (the sculpture is also the lid of an incense burner). Yaxchilan is worth a visit despite the unpleasant indigenous people, the boat ride across the river (which, by the way, forms the border with Guatemala) is beautiful, and the isolated, quite large archaeological site is a particularly peaceful place; many of the beautifully sculpted lintels, which are typical there, can now be admired in Mexico City or the British Museum. But the absolute highlight is Bonampak: The frescoes from the 8th century are magnificent. They depict processions of dignitaries, dancers, and musicians, battles, and women from the ruling family as they pierce their tongues and pass cords with knots through these holes as part of ritual acts to collect blood. But now I won't tell any more, it's already too long.

පුවත් පත්රිකාවට දායක වන්න

පිළිතුර