Touba, Senegal

Publié: 22.05.2022

S'inscrire à la Newsletter

We wake up in our bungalow at Campement le Cormoran - it's a pleasant 26 degrees in the morning and we appreciate the "cool breeze". Youssou, our driver and now almost friend, is already waiting for us and asks the standard question if we slept well and if it wasn't too hot.

There is some confusion about the payment. But then everything becomes clear, and after some back and forth, everything is paid, but we are not quite sure if we have been ripped off. Not easy, the quick payment situations and the conversion into the thousands of West African francs. This impression is reinforced when the friendly lady smilingly gives us a bottle of water. "Oh, you're going to Touba? It's super hot! So hot, you need water." With amazed eyes we watch as the woman takes a huge block of ice from the freezer, hits it with an object to produce ice cubes, fills them together with the bottle into a shabby cloth cooler, and hands it to us with a wide smile. We say that we won't be coming back to the river delta and won't be able to return the cooler. The woman nods knowingly and says it's okay, it's a cycle, everything comes back somehow. Alright then.

We get in the car, Miriam buckles up with some effort, as the seatbelt doesn't want to latch properly, and I get in the back of the car, having to sit in the middle because there is only a seatbelt there, a makeshift seat. We drive out of the small village, which consists of a tarred road in the middle, sand and houses with "shops" on the side. Racing past milk shops (recognizable by the graffiti-like paintings of cows on the walls), sewing workshops (where work is only done at night because it gets too hot during the day), alcohol shops (who drinks alcohol in a predominantly Muslim country?), indescribable things (and many of them), bakeries (recognizable by the many metal racks with baguettes on them). And horse-drawn carts, donkeys, goats, sheep, and masses of people in every corner, in every nook. Eventually, it becomes more rural, the sandy landscapes continue, the majestic baobab trees become more numerous and more impressive. We drive and drive, and then we have to stop quickly when I notice that a puddle has formed on the (surely original) Louis Vuitton rubber floor mat and my flip-flop is already floating on it. In the middle of the desert-like landscape, we stop, pour out the water, and also the remaining ice in the completely leaky container, and then we continue.

We need gasoline. At the first gas station we stop at, two gas station employees are lazing in the shade, leaning against the fuel pump. Once again, it looks like the gas station has been in need of renovation for decades. Rust, dust, dirt, ruins. Youssou stops, rolls down the window, asks something in Wolof, rolls up the window again, and we continue driving. "There is no gasoline here. Because of the Ukraine war. We will find another gas station," says Youssou. We nod and wonder where the next gas station is. We find one just a few minutes later. While our car is being refueled by the attendant, we decide to buy a cold Coke and some cookies at the gas station. As I get out of the car, I almost step into a rapidly spreading puddle, apparently flowing out of our car. Water or gasoline? I tell Youssou, Youssou tells the attendant, it's gasoline. Alright then. No one seems to find it particularly exciting, and after all our experiences that we have collected in just a few days, we accept the situation with a shrug and hope that Allah will take care of it. When we step out of the gas station with our acquisitions, we are briefly startled when we don't see Youssou or our car and briefly consider the thought of what would happen if our driver had just left without us and we would be left stranded in Senegal with only a Coke and salty cookies. Fortunately, our car is still there, propped up, and a mechanic is lying under it to see if the car needs any repairs. Youssou is of course still there too. Two minutes later, it's "all good", so we just continue. Today we visit the holy city of Touba, a kind of Mecca of Senegal, a holy city with even holier rules that forbid many things, such as the consumption of alcohol and cigarettes, and of course, female charms like flowing hair and bare skin, except for hands and face. The previous evening, we had tried to put together various disguises from our travel backpacks, made turbans and tied cloths around our hips to hide our pants because they are also forbidden, otherwise you might think we have legs. Of course, we respect the rules and want to dress as well as possible, which is why we document our attempts to find the right outfit on camera the night before and proudly present them to Youssou the next day. What does he think? We're not exactly sure. He says something like, "yes, it's probably good," but we're not completely convinced. In the car, he tells us that we will visit a market later to buy "appropriate clothes" for our visit to the mosque in Touba.

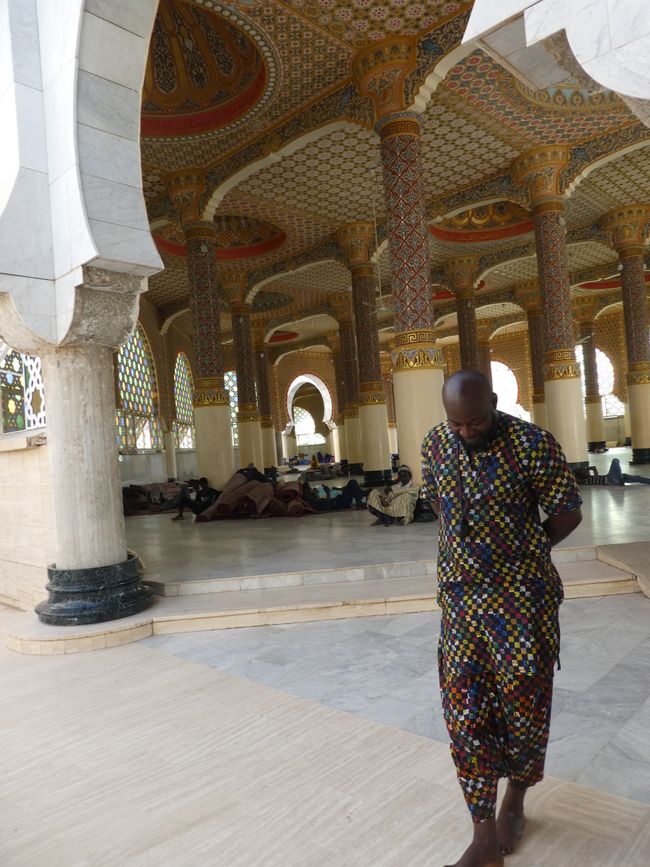

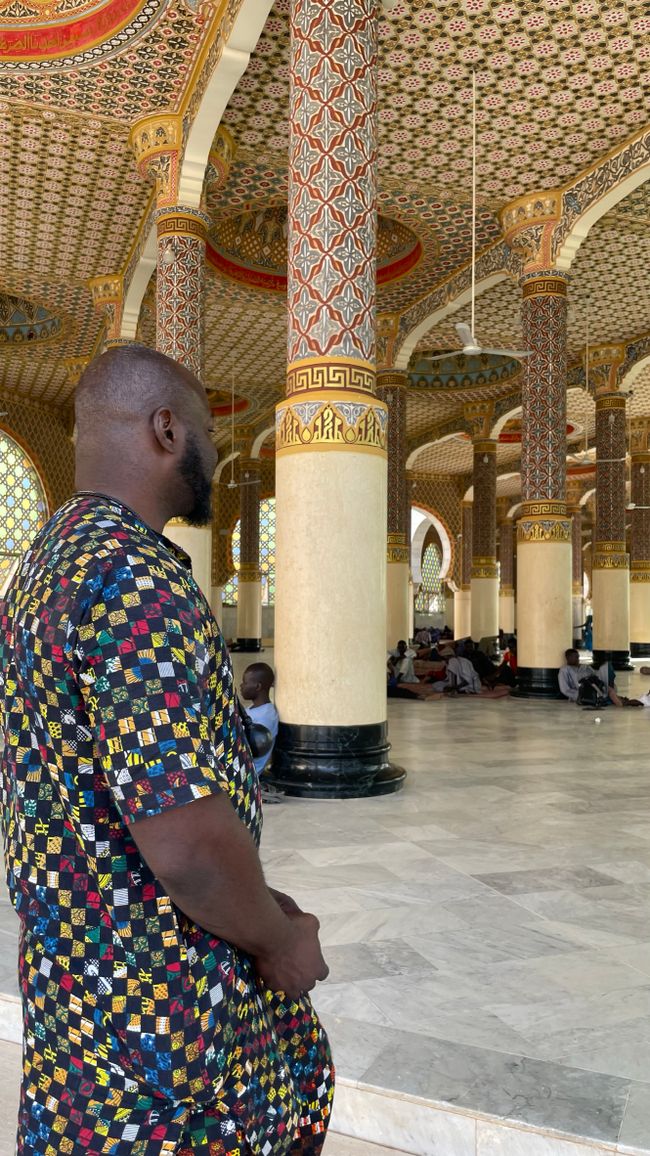

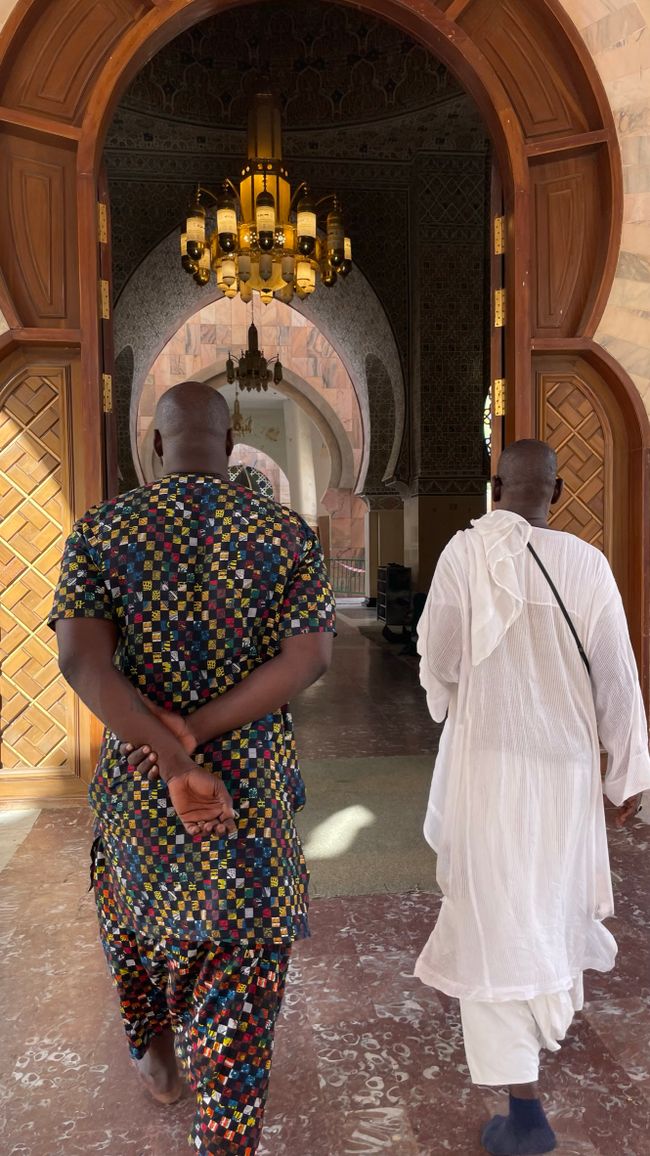

We eventually arrive in a suburb of Touba, Mbacké. And again, the typical city scenes, wild, unfiltered, bustling, colorful, loud, full of life and impressions that we can only process to a limited extent. Then we stop, get out, meet someone named Ismael who seems a bit strange to us, then he gets in the car with us and we continue driving. As always, no information. Youssou says nothing, we don't ask anything. So we continue driving, let ourselves be driven, wherever it may be, accept that we don't know, continue looking out the window, and marvel at this foreign world. Then we stop at a house, Youssou gets out, that's our sign to get out too. We are standing in the clay and sand, and then we enter the house. A small corridor, a room there, Youssou takes off his sandals, slides the curtain aside, and disappears behind it, together with Ismael. The curtain falls, we are outside and don't quite know if we should come in now or wait or what. We look at each other and try not to laugh because we are a bit uncertain about the customs and don't want to do anything disrespectful or wrong so close to the holy city. Suddenly Youssou's face appears again at the side of the curtain. "Come in!" - Oh, okay. So we should come in. We also take off our shoes and enter the room, a red carpet on the floor, two mattresses where people are sitting, a fan pointing towards the ceiling, a suitcase with clothes, a coffee pot. We sit and wait. Once again, no information. We're not exactly sure how to behave because nobody has really instructed us. Whether I want coffee - Miriam is no longer asked, as she gladly refrains from drinking coffee since it only consists of Nestlé instant coffee. So I get a coffee and give Miriam a sip, because if anything, we want to both be poisoned. In the room, Youssou, Ismael, Miriam, and I, and: the king. Or that's what we'll call him later, or rather: the beautiful king. He sits opposite us on the mattress, lounging around like us on the floor, but still setting himself apart from everyone else. He wears a plain, ochre-colored robe, like the sand, his facial features soft, his aura strong, he has a special charisma that somehow captivates us. We speak, as always, in German with each other and comment on the situation, the room, and what is happening, and when the word "attractive" is mentioned, we are briefly startled because this word is easily understandable in French or English as well. So we agree on "the beautiful king". The beautiful king is of course not a real king, but he is still a big shot, or a religious leader, or at least an important man. He introduces himself to us as the grandson of the famous Ibrahima Fall, the founder of the Baye Fall movement. We are amazed, as we have seen the king's grandfather everywhere in Senegal as graffiti, stickers, and tattoos. The king speaks English with us, and quite well at that. He also seems to be highly educated, talking about his niece who lives in London and is also a speech therapist (or has attended speech therapy? We only understand half of it once again). We exchange some information, but only on the surface. Suddenly, a snapping of fingers is heard outside the curtain, the king hums a "yes", and a servant (also a Baye Fall?) comes in, crawling on his knees with his head lowered, enters the room, puts down a second coffee pot, submissive, turns around, and leaves the room with his head held high. Another Baye Fall comes in, not on his knees, but still humble, wearing striped clothes and a belt with various tools around his waist. He is supposed to repair the fan, kneels down next to it, and starts working on the device. Then nothing happens for a long time, and then suddenly a feeling of departure: Youssou tells us that we are now going to the market to buy "appropriate clothes" for our visit to the mosque in Touba. Another Baye Fall accompanies us, this is his task, says Youssou. We make our way through sandy paths and crowded streets to the market, where we get out, once again we are the only white people in sight, and yet the Senegalese are respectful and do not stare at us (at least not obviously). We walk through the market, but not far, we stop at a stand that sells only long robes and dresses. However, to our surprise, it is not us who choose the clothes. We watch in amazement as Youssou and the Baye Fall get to work, taking the clothes off the racks here and there, or even tearing them off the mannequins to examine them more closely. Discussions, shop talk, we stand there and just watch. At some point, they then hold two of these dresses in their hands, the fabric reaches to the floor and the sleeves are long, and they also have a kind of hood that we can use as a headscarf. But the best part: they are bright orange and bright pink. "C'est bon?" Youssou asks, we shrug and say: Yes, of course. So off we go again, back to the car, back to the beautiful king. When we enter the room again, by now three people are already working on the fan, and we wonder if they know what they are doing. We sit down again, wait, smile, what will happen now? At some point, Youssou asks if we're hungry. We look at each other. Okay, I think we're going to eat here. And shortly afterwards, another Baye Fall servant comes into our room, with his head held low, and puts a large metal bowl, covered with a kitchen towel, in the middle of the room on the floor. The king, Miriam, and I receive spoons, Ismael and Youssou eat with their hands, as is usually done. The kitchen towel is lifted and reveals: fish and vegetables, poisson et légumes, on a bed of seasoned rice. The fish (or fish?) is lying whole on the rice, with bones and small joints in between, and cassava, carrots, and white cabbage. We look at each other, now is the moment when we first eat local food according to local customs, and for a brief moment we hope that the preparation and hygiene in the kitchen will be compatible with our digestion. We eat rice and vegetables and discreetly avoid the fish with our hands, for safety reasons. Youssou picks through the fish and rice with his fingers, and repeatedly picks out the fish meat, throwing the best pieces, already chopped up, into the "food corner" of the king, who then takes them with his spoon. He compresses what he himself eats into a ball with his fist to put it in his mouth. A new technique, different from what I have observed/practiced in Indonesia, for example. It tastes very good to us! Then the beautiful king looks at us and asks, "why don't you eat the fish?" - oh no, now courtesy dictates that we try the fish, no matter what. We eat some of it, it tastes delicious, smoked, grilled. We close our eyes and think, let's just do it, and hope that no nasty surprises await us later. Miriam whispers to me, "I have apple schnapps in the car." and we agree that after the meal we will go and have a sip of schnapps to disinfect ourselves from the inside. In anticipation, we had bought Luzerner "Birewegge" at the airport, originally more as emergency rations, but now they serve as a thank you gift to distribute. When I take the Birewegge out of the backpack and announce that we also have something from Switzerland to trade, everyone is interested, the pack of Birewegge circulates in the group, and every time we hear, "oh, organic!" - that seems to be particularly interesting somehow. In the end, the pack of Birewegge ends up back in my hands, and suddenly everyone gets up and leaves the room, even though Miriam and I are still eating. We look at each other, laugh again because we don't understand how the social rules work, and stop eating too. Everyone disappears for minutes, we quickly take photos of the room, and of the fan, which is still broken. Then the king comes back and we offer him and Youssou some Birewegge and hope they like it. They politely say thank you, but we're not entirely sure if they really like it. I ask Youssou for the car key, "we need to get something from the car." So we step out into the desert sun heat and quickly go to the car. A quick rummage in the backpack and a flask appears, our healing schnapps - for safety's sake, we take three sips and hope for the best. Some children then come, two, three, seven, eight, a whole bunch of children, they talk to us, stretch out their empty hands, and ask for something to eat. Miriam gives them one of our granola bars, which leads to even more children rushing towards us, and in turn, we quickly retreat into the house. Mixed feelings, we would have liked to have hundreds of granola bars to distribute, but it's not possible, in the end, we have to ignore the kids and disappear into the house. How to deal with it? Often we don't even have time to reflect on such situations. We are already back in the house, supposed to change clothes, it's time to leave. The bathroom is right next door, we enter the room and the king brings us two pairs of flip-flops and washes them with water. We think: this man, who is being served here and is apparently an important man, washes our flip-flops for us, serves us, and what are we then, also queens? We change clothes, laugh a lot, have a small photo shoot, and in the background are men's underwear hanging on a clothesline behind the king. As we show ourselves, everyone is satisfied, no great enthusiasm, just "good," and we sweat a lot, now we have long pants, long-sleeved shirts, and on top of that our neon robes, and by now it's really 42 degrees outside. And inside too because the fan problem doesn't seem to be solved, not even with three vigorous servants. Now we're off to Touba, and we quickly arrive in the city. Even in the car, we cover our hair and are ready to visit the grand mosque. At the entrance of the mosque, we entrust our shoes to a woman sitting on the ground with some children so that she can look after them while we explore the mosque. Youssou had told us earlier to wear socks, as the marble floor of the mosque gets very hot. Miriam wears white socks, I wear gray ones, and it works well, the floor is very clean and pleasantly warm under the socks. In the mosque itself, or rather in its many buildings, hundreds of people lounge on carpets on the floor in the shade. They doze off, sleep, or just lie around - it's just too hot and it's Ramadan, they haven't eaten or drunk anything for hours, so their strength is only enough to lie around. The guide explains that in the evening, there is free food for all residents of Touba, or anyone who wants to come, in the mosque, which is why there are so many people waiting here.

The mosque itself is beautiful and impressive, and the minaret in particular looks magnificent, surrounded by many birds - its shape resembles a huge lighthouse that guides us on the right path (not inappropriate, as the call to prayer is also called from the minaret). Then something unexpected happens again: we step out of the mosque with our socked feet onto the street, walk on clay, stones, and an incredible amount of sand, and giggle because we miss our shoes, but no one else finds it strange that we are walking around in socks like this. It should be mentioned that many people in Touba walk around outside and inside the mosque with leather slippers that look like leather slippers.

We arrive at another place that is obviously also holy, and the guide tells us that there is "Holy Water" here. Whether we want to drink some of it? We look at each other, wide-eyed, thinking of cholera and other diseases, and politely decline. He laughs. But Youssou would like to have some of the holy water, and he buys a PET bottle from a roadside vendor, where several women sellers sit with many PET bottles, apparently this is a business here. Miriam and I make a mental note of what the bottle of holy water looks like, for fear of suddenly coming across it in the car and accidentally drinking from it: poisoning for us, less holy water for Youssou - we really don't want that. At the end of our tour of the mosque in Touba, our guide asks us to donate, and we think about how much money we would like to give when he adds, "you can donate if you want. Give 20,000 per person" - wow, almost 30 euros per person? Since this comes across more as a demand than a request, we give the money, hoping to appease Allah, and hoping that the money will actually be used to finance food for all the people. We can't know for sure. We retrieve our shoes, leave another small donation for the woman, and return to the car, where, due to the incredible heat, I gulp down a 1.5-liter bottle of non-holy water in one go.

We make our way to our next stop, an eco-lodge that we had already booked, which is halfway to the Lompoul desert. Before that, we linger in the city when suddenly a deafening "singing" blares from all kinds of loudspeakers of the mosque and as a result, surely a thousand people, all in their Baye Fall attire, come running towards us, streaming past our car, where did they come from, where are they going? We can hardly believe our eyes once again and sit speechless in the car, filming. Then we continue, out of the city. Youssou asks if we would rather stay with his friend (the king), he would accommodate us for the night and it is also much closer than this eco-lodge. We briefly find the idea exciting, but then too exciting, and I say, "Let's drive to the lodge instead. We have a room reserved there, the standard is such that we will feel comfortable, and it's safe. Who knows how we would sleep at the king's place." - and that's what we do. We continue, and the landscape changes, becoming more rural, quiet, we leave the city and the noise and dirt behind. The road also gets worse, at first only the edges of the asphalt crumble, then the road is gradually devoured by the sand, and eventually we are driving only on a sandy track. The tires skid on the sand, but Youssou has everything under control, driving us safely and curvily through all the sandy potholes, the sun is slowly setting, on the left and right of the "road" there is only land. Trees, occasional sheep and goats, and the red sun ball, which is slowly approaching the horizon. An incredibly wonderful and peaceful moment, for a brief moment we exclaim out of the window, "this is the good life, we must enjoy it!" and then we fall silent, exhaustion slowly overtakes us, and we wish to arrive soon, take a shower, and fall into bed after all that we have experienced.

Suddenly, the sun is gone, it is dusk, and then it is pitch-black. In between, we still pass through villages, and once again, we adjust our concept of "the deepest Africa" as now there are only clay huts with thatched roofs and the famous village well, where women fetch water and transport it home or to the next village on their heads in buckets. We can no longer imagine a deeper Africa. We look back on just under a week in Senegal and realize that everything has become more intense with each day of our journey, the impressions deeper and more intense, the landscapes even more barren, and running water and working electricity have become a matter of luck. We wonder if this was the zenith or what will happen tomorrow.

Then suddenly we arrive. The navigation on Youssou's phone says we are there, even though we are in the middle of an African village, in complete darkness, and there is no sign of a lodge or hotel anywhere. Youssou wants to drive a few more meters, when suddenly and very quickly we get stuck in the sand and every attempt to get out only results in the nose of the car digging deeper into the sand. Youssou curses, we are completely calm and say nothing, unsure how to deal with the situation that on the one hand we are not at our lodge, and on the other hand, hopelessly stuck in the sand. Youssou instructs Miriam to take the wheel, she accelerates, the car smokes and stinks and Youssou and I push against the car with all our strength - and nothing happens. By now, we have probably attracted attention in the village, and two men and two boys, about seven years old, come out of the darkness, curious, and stare at us. First, Youssou asks about the Eco-lodge and it turns out that we have to drive another 4 km in the opposite direction, or so we think. To be sure, Youssou wants to call the lodge, and he is puzzled when we give him the number, as it is not a Senegalese phone number. When someone answers the call, it quickly becomes clear that we don't even have a reservation at the lodge. Well, we do have one, but apparently the lodge doesn't. On the phone, we receive cryptic directions again. Miriam and I no longer understand what is going on and thoughts run through our minds. What if we can't go to the lodge? After all, Touba is 3 hours away. Will we sleep in the car? Will we stay in a hut in the village? Is that possible? We wait, try to calm down, and I say that I trust that it will turn out well. In the end, there has always been a guardian angel for us.

We make a new attempt to get the car out of the sand, this time I sit at the wheel. The image is burned into my memory: I sit at the wheel of this old car, wearing loose flip-flops, and try to find the clutch's biting point, while pressing on the gas pedal with determination. Outside: absolute darkness, the bleating of sheep. In the headlights: Youssou, Miriam, the two men, and the two boys, who push against the car, look in my direction, contort their faces with effort. The car creaks and then it moves, it's a triumph, I reverse, but where to, I can't see anything, so I just get out of the sand, keep driving, and suddenly Youssou starts waving his arms frantically. I brake hard and take a deep breath, done it. When I then open the car door to get out, I am astonished, I have stopped just two centimeters in front of a thatched hut! For a moment, the image flashes through my mind of the car crashing into the hut or even driving on with the whole hut. Oh dear.

We continue driving, out of the village again, back onto the sandy track, and I have the feeling that I felt more comfortable in the village than driving through the pitch-black steppe, with more potential sand pits where we could get stuck, and there wouldn't be any nice village people to help us out. Youssou is on the phone again, once again with the lodge. He says something into the phone, then the connection is cut off. We are uncertain, as Youssou has been calm all along, but now he seems to be at the end of his nerves too and curses - in German: "scheiße, scheiße!" He tells us that he asked the guy from the lodge whether it was to the left or right of the road, and the answer was, "just keep going straight." We are desperate. But then suddenly, a wooden sign with heavily chipped paint appears, and it says "Ecolodge de Koba." We also see lights. Thank goodness and finally! We get out of the car and are infinitely relieved to have finally arrived somewhere. And as I step out of the car and relaxation sets in, I suddenly realize that I urgently need to use the bathroom, the 1.5 liters of water have to come out. I ask one of the men at the lodge if there is a bathroom. He looks at me, shrugs his shoulders, and says, "yes, each bungalow has a toilet," then turns around and leaves. I stand there rooted to the spot and don't know whether to laugh or cry. Fortunately, Youssou helps me, and then I am allowed to walk through an inhabited bungalow next door, come out on the other side, in the open-air bathroom, and there is a toilet, hallelujah! The fact that the water doesn't work is a minor issue, I pour enough water from the nearby 10-liter bucket into the toilet to flush it. Then we sit there and wait. Still completely perplexed and excited, Youssou is already relaxed again and is on the phone, with whoever. We eat some nuts, our last provisions, and wait. And wait. Nothing happens for a long time. We go through the day in our minds. Wonder, laugh, marvel. Miriam says, "Well, that was probably really the zenith! It can't get any worse than this," and exactly 3, 2, 1 seconds later - power outage. Suddenly we are sitting in the dark, for a moment you can only hear the chirping of crickets, and then we are overwhelmed by a real fit of laughter. We laugh, cry, cry with laughter, and laugh again. If we had to make a film about things that can go wrong while traveling, we couldn't have written a better script. I turn to Youssou. "Youssou. What is this? Today we were blessed by the king, we donated money to the mosque. But Youssou, where is Allah now?" - we can't stop laughing. It will probably be another hour until we finally get to bed. And we fall blissfully asleep and dream of thatched huts and sand pits.

S'inscrire à la Newsletter

Répondre

Rapports de voyage Sénégal