El Salvador: San Miguel & Perquin

Published: 23.03.2018

Subscribe to Newsletter

We took a taxi to the bus terminal in San Salvador. We didn't know exactly how bus travel in El Salvador works and decided to figure it out as we went along. As soon as we got out of the taxi at the terminal, we were surrounded by men who wanted to know where we were going. Just as we said "San Miguel," our luggage was packed and we were loaded onto a bus. We didn't even have a chance to ask about the price, departure time, or anything else before we were on the bus. That's how it works here. The bus stayed at the terminal for a while, so we were able to observe the activity outside the window and draw conclusions about public transportation. It turns out we were on a special bus, different from the usual chicken buses. The bus was supposed to go directly to San Miguel and was similar to a fancy car you might find back home. However, the seats were so narrow that I struggled to fit my legs in. You can imagine how uncomfortable it was for Jörg. We later found out that the special buses were about twice as expensive as the chicken buses. We paid $5 per person for the trip to San Miguel, which took about 4.5 hours. Apparently, our understanding of "direct and non-stop" is different from that of the Salvadoran people, because the bus made several stops and kept getting more crowded. Since there was no chance for Jörg and me to sit together on the narrow bench, we had Salvadoran students as seat neighbors.

One interesting and amusing thing about El Salvador is that you don't need to go to a store for your daily shopping. You can simply do all your shopping on the bus. Vendors get on everywhere and offer all kinds of goods. The range of products includes various vegetables (tomatoes, onions, cucumbers, peppers, etc.), electronic devices like spare batteries, chargers, headphones, and power strips, all kinds of nuts, chips, popcorn, various sweets, chocolate, cookies, marshmallows, milk, cheesecake, sandwiches, tortillas, grilled chicken skewers, drinks, fruit juices, water in plastic bags, underwear, leggings, pants, medication for blood pressure, fever, and pain, newspapers, sunglasses, etc. A truly colorful mix. The most popular item was socks, which half of the passengers rushed to buy from the available packs of four. Who buys socks on the bus? None in our size, that's for sure. It was especially amusing to listen to the vendors passionately promoting their products, loudly advertising the advantages and quality of the items, and repeatedly mentioning that they were "American products." Normally, the socks cost 8 dollars for a pack of three, but today they were on special offer - 4 pairs for only 3 dollars! How could we pass up such a bargain? Jörg's seat neighbor had a hard time choosing one of the available colors for the socks.

Along the way, we also bought candies and other snacks from the vendors. Firstly, it was usually cheaper than in the store, and secondly, in a country where so many children and young people fall into the clutches of criminal gangs, it seemed worthwhile to buy things from young people who have chosen an honest and peaceful path in life. Usually, we are very restrained with money donations to beggars, especially those who specifically approach tourists. But in such a poor country, we sometimes have a small coin left over for people who climb into buses without legs and ask for a small contribution for their families. After all, there is no social security, no disability benefits, and certainly no professional prospects for disabled people here. And when you give such a man just 25 cents, he smiles gratefully and wishes you God's blessings and a wonderful day. Thank you, we wish the same for you.

Arriving in San Miguel, we grabbed a taxi to the hotel. After just this first ride, we had already seen enough of San Miguel and were glad to only spend one night here on our way to Perquin. The major cities in El Salvador are really not for the faint-hearted, especially for those who are not comfortable with firearms. Firstly, there are even more firearms here than we had experienced so far in Guatemala. In Guatemala, it was mainly security personnel who carried weapons in front of shopping centers, larger pharmacies, and banks. But here in El Salvador, there is at least one man with a rifle positioned in front of every imaginable small shop. Secondly, in Guatemala, the security personnel hung their guns from a strap over their shoulders and held them loosely in their hands. But in El Salvador, people have their finger on the trigger at all times. A twitch would be enough to send the pump-action weapon into the afterlife. But somehow, eventually, you get used to it. We had eventually gotten used to all the guns in Guatemala as well.

One particularly impressive moment for me was when Jörg suddenly told me to look out the taxi window. The taxi was parked in front of a store for motorbikes and bicycles. And there, engrossed in conversation, stood a man with a thigh holster over his jeans, casually leaning against the wall with his finger on the trigger of his pistol. While I stared at him in surprise, he suddenly looked directly at me and I could almost literally see down the barrel of his gun. And me? I just smiled friendly at him, and he smiled back. Honestly, what else can you do but smile friendly (and hope that the man doesn't suddenly have spasms)?

After just this first taxi ride in San Miguel, our interest in the second largest city in El Salvador had definitely diminished. The major cities in El Salvador are really not very appealing, especially since gang crime is most prevalent here. But more on that later.

The bus ride to Perquin was also uncomfortable. It was a long way into the mountains and there were no "especial" buses here. We didn't even know what the security situation was like on the way there, as we had received very conflicting information from the people we had asked. As we were told, foreign tourists are practically non-existent in eastern El Salvador; the few who do travel through the country can only be found in the west. So, we decided to look for a car to take us there. We asked at the hotel, and it turned out that El Salvador is not prepared for tourists with such special requests at all. The woman at the reception was quite surprised by our inquiry and said that we would probably have to ask a taxi on the street. Another hotel staff member chimed in and said he would ask his son if he had time. And indeed, the next morning Carlos, the son of the hotel staff member, was waiting for us outside the hotel to drive us to Perquin. We felt more comfortable riding with someone whose father we knew worked at the hotel, rather than just any random taxi driver off the street.

The car ride was only about 2 hours, half the time it would have taken by bus. Unfortunately, Carlos was not very talkative, so the ride was quite quiet. When we arrived in Perquin, he gave us his phone number so that we could contact him on WhatsApp for the return trip. We just had to notify him 3 hours in advance. It was a good deal for him, apparently he didn't have much else to do if he could be back there within 3 hours. And for us, it was a comfortable and safe way to travel, a classic win-win situation, I would say.

Perquin is a charming little village in the mountains of El Salvador, near the border with Honduras. The town is mainly visited by local tourists and school groups. It is known for being the stronghold of the FMLN party, the guerrillas, during the civil war. There is a museum on-site that tells the story of the civil war and a reconstructed guerrilla camp.

Our booked hotel Perquin-Lenca was incredibly beautiful. It is located on a hill in the forest and offers a good value for money, a pretty good restaurant, and hammocks under the trees where you can relax and unwind.

In the afternoon after our arrival, we visited the town and took a stroll around. And that's when it happened - we were robbed for the very first time: Jörg had just bought a can of orange soda in a store and was about to drink it when a man walked by and took the can out of his hand. At first, I didn't really understand what was happening; the guy was babbling about the soda not being real orange, I don't know, we didn't understand it. Anyway, he took the can and walked away. We stood there dumbfounded, not understanding what just happened, while two other older men who had been sitting by the roadside and watching the scene burst out laughing. Well, minus one orange soda. "Gschäch nüt schlemmers," as they say in Switzerland. "Cheers," we wished the audacious soda thief.

Through the hotel, we were put in touch with our guide Rafael. Late in the evening, we sent him a message, and he was ready to accompany us to El Mozote the next morning. Rafael is a war veteran of the civil war and fought on the side of the FMLN guerrillas. His body bears clear marks of the battle; he has been shot multiple times. For example, all the fingertips are missing from one of his hands.

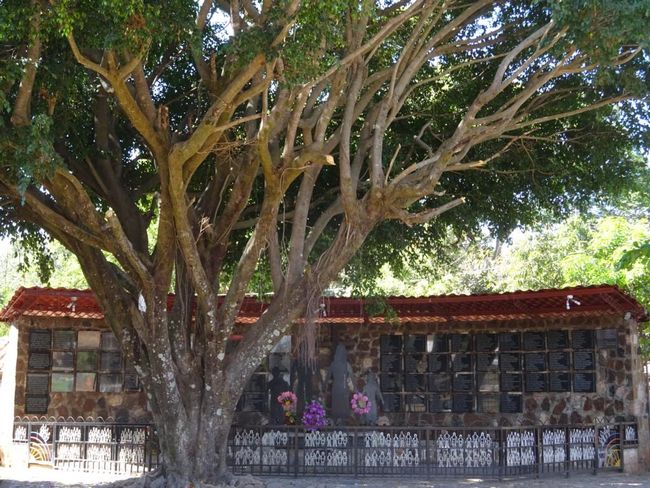

El Mozote is home to a memorial site for a massacre where approximately 900 civilians (including women and children) were killed by government soldiers during the civil war in December 1981. The massacre was the most violent attack by government forces on the civilian population during the civil war and is considered one of the largest war crimes in the history of Central America.

To get to El Mozote, we went by "transporte informal," as Rafael put it. That means we set off on foot and hoped to meet acquaintances of Rafael along the way who could give us a ride. So, we changed vehicles a few times, from the bed of one pickup truck to another, while we had to walk a stretch of the road in between until we met the next acquaintance. Fortunately, we only had to walk a small part of the (quite long) route on foot; war veterans know each other here.

The memorial site itself is not very spectacular. There is a monument, and behind it, the names of the victims and their ages are engraved on stone plaques. The stories told by Rafael himself and a survivor of the massacre were more moving. On that fateful day, men, women, and children were led in groups to the square in front of the church and killed one by one. The young girls were taken to a nearby hill, raped, and then killed as well. There is a book that tells the story of the events, written by another survivor named Rubina Amaya, which I bought on-site and am currently reading. However, since it is only available in Spanish, it takes a bit longer to read. In the book, Rubina tells in a heart-wrenching way how she was separated from her 4 children on that terrible day. She managed to escape, but she had to leave her children behind. As she hid, she recognized their screams as they were being killed.

When we were at the monument, two other women came by to leave flowers for their families who had also lost their lives in the massacre.

Nevertheless, it was surprising to see that the area was once again bustling with activity and that so many people were living here. Rafael explained that many people leave the villages during the months of November and December to work in the coffee fields. These people were spared from the massacre and later returned to the region, starting new families and participating in the reconstruction efforts.

The civil war in El Salvador lasted from 1980 to 1992, 12 years of fighting. The main reason for the war was the prevalent poverty among the rural population. The wealth generated by coffee exports in the 20th century was controlled by only 2% of the Salvadoran population. At the same time, revolutionary ideas and the spark of armed guerrilla resistance came from Cuba and also from Nicaragua. Interestingly, you can find pictures of our friend El Commandante Che Guevara in El Mozote and many other places in El Salvador. Looking back, we are very glad that we started our journey in Cuba, as this experience has contributed a lot to our understanding of the climate of revolutionary guerrilla movements in this part of the world.

On March 24, 1980, Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was striving for social equality and peace, was assassinated while celebrating Mass in the chapel of the Hospital Divina Providencia in San Salvador. This murder led to an armed uprising, which turned into a civil war later that year.

At that time, the US government supported the military dictatorship in El Salvador, turning the country into another battleground of the Cold War. Apart from military advisors and equipment, enormous amounts of money were also transferred to the country. The anti-guerrilla unit responsible for the massacre in El Mozote was formed and trained by US soldiers. Without the interference of the Americans, the Salvadoran military would have long been doomed, and the war would have ended. So, the financial support from the United States resulted in a prolongation of the conflict. Until the peace talks concluded in 1992 between the FMLN and the Salvadoran government and a ceasefire agreement was reached, the war claimed about 70,000 lives, mainly civilians.

An interesting fact that brings a smile to your face: Rafael told us that the guerrillas bought their weapons from Nicaragua. And that was from the military that had received these weapons from the US during the civil war in Nicaragua. It's nothing new that Americans eventually end up fighting against their own weapons.

For the return journey from El Mozote, we took the bus, which only runs a few times a day. We told Rafael that we planned to visit the museum and the guerrilla camp in the afternoon. He immediately offered to accompany us there as well.

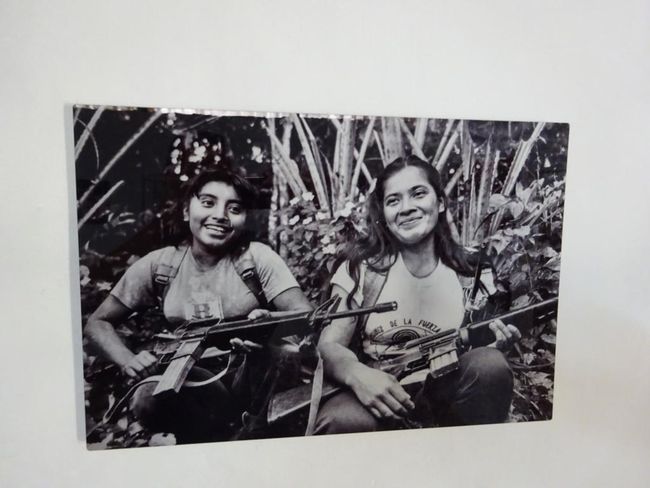

The museum is relatively simple and consists mainly of photographs. There is little text and explanation. So it was good to have Rafael with us.

It was fascinating to watch Rafael as he got into heated discussions with other local museum visitors, especially about whether the situation had actually improved or not. Jörg and I stood there, trying hard to understand everything the Salvadorans were saying to each other, but it was sometimes too difficult. Nevertheless, it became clear that the war and the associated social issues still occupy the people. One of the men we met there told us that some of his uncles had fought on the side of the guerrillas, while other uncles served in the Salvadoran military. It was apparently not uncommon for the war to divide families as well. We asked him how the climate is in the family now, whether there are still conflicts? No, he said, there are no more conflicts, it is peaceful in the family, it's all in the past.

We also asked him what the veterans did after the war. Most of them simply went back to being farmers, as before, Rafael told us. Some are now guides, like himself.

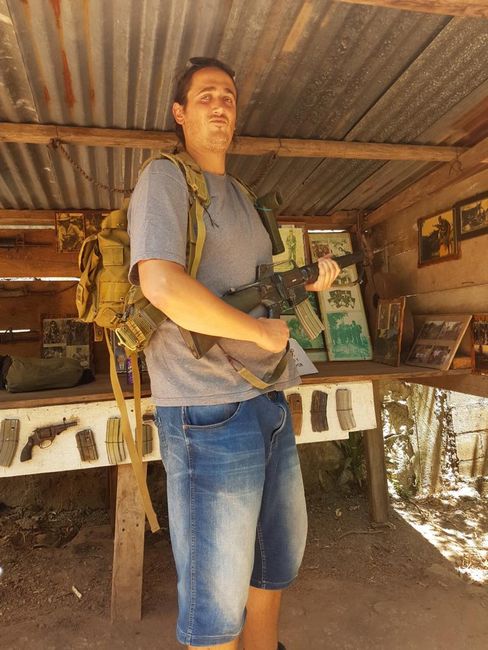

In one of the rooms in the museum, the weapons used by the guerrillas at that time are displayed. And Rafael really got excited there. He demonstrated every rifle to us, diligently unscrewing and handling them. These weapons had been his companions for a long time, and that was evident. The other men in the room also caught his enthusiasm, and they all exclaimed in admiration when Rafael mentioned the calibers, the range of the guns, and everything else that was important about firearms. "Ooooohhhh! Ahaaaaaaa! Woooow!"

And me? I just stood there bored, unable to develop any enthusiasm for war machinery, and there were no handbags to buy there. 😊

Afterwards, we went with Rafael to visit the reconstructed guerrilla camp. It's clearly a tourist attraction, but still quite entertaining. You can see the tents the guerrillas used, underground bunkers, a reconstructed station of the guerrilla radio "Venceremos," and once again, various weapons, bombs, and war artifacts. In addition, there are some rather untrustworthy-looking suspension bridges through the forest that you can walk across (if you dare). It was quite funny to visit the camp with Rafael. He repeatedly emphasized that there used to be no walking trails, as they would have been immediately spotted from the air!

Afterwards, Rafael brought us back to the hotel, and we said goodbye. It had been an exciting and entertaining day with him.

Since there isn't much else to see in Perquin, we called our friend Carlos for the next morning and drove back to San Miguel with him. He took us straight to the bus terminal, where we took a bus back to San Salvador later that day.

We really liked Perquin. As we learned, very few foreign tourists find their way here. Yet, it is a charming little town in the mountains with a pleasant climate, where you can spend a good 1-2 days. You don't really see any guns here (except at the museum), it is very calm, safe, and leisurely, and the people are very friendly and helpful (unless they steal your drink).

Subscribe to Newsletter

Answer

Travel reports El Salvador