Day 29: Mount St. Helens

Published: 04.07.2018

Subscribe to Newsletter

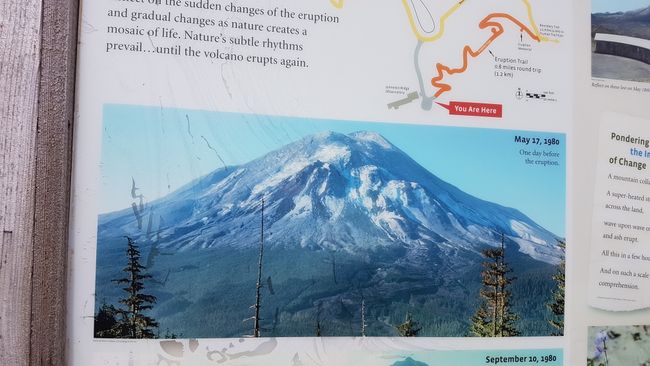

After breakfast, we explore Paradise Point State Park with a short hike. It promises a waterfall and a path along the river. The waterfall is a trickle and the path is a dirt trail through the reeds. We don't discover a paradise spot and quickly leave the park. The landscape along the interstate (major highway) is unremarkable, but we quickly reach Silverlake. One of the visitor centers for Mount St. Helens is located there. We pay $5 admission and gain access to a museum and a theater with a film. The film tells the story of the volcano and illustrates its impact on the landscape. Because in recent history there was an eruption. 38 years ago on May 18, 1980, it erupted. Maybe there is someone among you who remembers it from the news. We were all clueless.

After 123 years of inactivity, more than 10,000 earthquakes shook the volcano in the spring of 1980, awakening Mount St. Helens. A large bulge formed on the north side of the volcano and the mountainside swelled at a rate of 1.5 meters per day, indicating that magma was rising inside the volcano. At 8:32 a.m. on May 18, 1980, gravity suddenly took hold of the growing mass and triggered one of the largest documented landslides in history. The masses of earth slid down the northern flank and raced through the valley to Spirit Lake, crashing into rocky ridges and continuing 22 kilometers westward. The landslide surged through Spirit Lake, doubling its surface area instantly, but making it only half as deep. Compared to before the eruption, the lake's water level is now 60 meters higher. The detachment of the summit released pressure and triggered a lateral explosion at a speed of 500 km/h, with hot gases and rocks reaching temperatures of over 300 degrees Celsius. This explosion shattered, felled, and scorched 600 square kilometers of forest area in about 3 minutes. One of the first victims of the explosion was the 30-year-old geologist David Johnston, who was monitoring the mountain's activity from what was believed to be a safe distance. However, unfortunately, the mountain erupted sideways rather than upward, reaching him in less than a minute. The ridge where he was located has since been renamed in recognition of his contributions to geology and because of his untimely death. In total, 57 people lost their lives that day, and 150 had to be rescued despite prior evacuation and warnings.

There are many facts about the eruption that are very interesting but would exceed the scope here. So I conclude my digression and report on our day.

The films are very illustrative. They explain and show well the events. Erik participates once again in the Junior Park Ranger program and receives his badge. Now it's time to take a closer look at the scene of the events. We drive 59 miles near the Craters to the Johnston Ridge Observatory and explore there. Erik wants to watch the film first. There are 2 films shown. One film is about the eruption of the volcano and the second shows how nature has grown since then. Both are very interesting. Especially how quickly nature regenerates. Within a short period of time, life returns and creates new changed habitats for returning or new animals and plants. There are still stories of some people who barely escaped. The exhibition features interactive games where you can jump and create small earthquakes on the seismograph or feel volcanic activity compared to a helicopter landing using your hand. I am surprised that there were no 'classic' red lava flows in the records. The ranger explains to me that this is due to the type of rock. Here, the lava explodes instead of flowing. We walk a small loop trail and observe the changed landscape from above. We actually wanted to do another hike, but it's already 4:30 PM and we still have an hour drive to the campground. We arrive on time at Seaquest State Park, our place for tonight.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Answer (1)

Regina

Frank will sich daran erinnern, ich nicht, an 1980 habe ich andere schöne Erinnerungen. :)