'The Warm Heart of Africa'

Publicatu: 13.02.2017

Abbonate à Newsletter

That's what Malawi is called and that's what the Malawians say about themselves. And rightly so, I think, almost all the people here are really friendly, laugh a lot, always ask how you're doing. But let's start at the beginning:

After a long but smooth journey, I finally arrive in Blantyre, Malawi via Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, Johannesburg in South Africa. Since it is the second largest city in Malawi, I expect a big airport, but when landing, I rather feel like I've arrived at a farm: there is only a narrow runway, the plane has to turn on the spot, and the tower looks like a rooftop. Upon arrival, I have to buy a visa for $75, I pay dutifully, and the officer tears off a piece of paper from his notebook and gives me the scrap of paper. Very official. Fortunately, the driver from the hospital is already waiting for me outside in the ambulance. Did the hospital not have an ambulance for almost a day? I feel guilty. Well, we're off to Phalombe in the southeast of the country, 5km away from the "Holy Family Mission Hospital". After about 2.5 hours, we arrive and I am warmly welcomed by the others who have already been here this month: two students, a gynecologist, a midwife, and an EMT. It feels a bit strange to be here now, it always felt so far away, but now I'm actually here. We go into the house and the first thing someone says is, "Oh, we have electricity!".

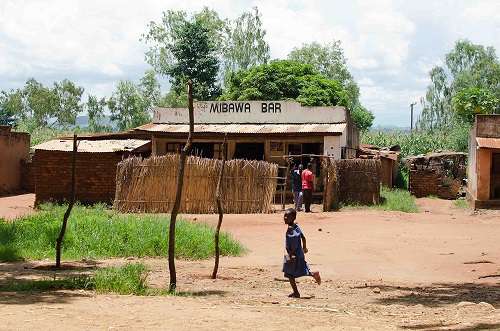

In fact, I find it difficult to settle in during the first few days, the culture shock is much bigger than expected and somehow many things are different than I expected. Things we take for granted become a problem: as mentioned before, the power often goes out, or you go to the toilet or take a shower and there's no water. It's very hot and due to the subtropical location, there is high humidity, I even sweat while sleeping. That means: always drink enough. But where to get water? Three other students from previous months have tried drinking the tap water and were punished with a week of diarrhea. I don't want that, so water has to be bought. But it's about 5km to Phalombe. You can walk or take a "bicycle taxi" (sitting on the luggage rack, apparently a common means of transportation here). But when I think about it, I feel like a white colonial lord, so I'll walk. For food, there's a small "market" right at the hospital with some bread-like rolls in plastic barrels and some vegetables and fruits. The internet to stay in touch with home through the SIM card doesn't work at all, and then it works very poorly. The nearest ATM is 2 hours away. And so on and so forth. So, there are many small and big problems here and there that make it harder to get started than I thought. But by now, I've been able to adapt a bit and it's actually working quite well and it's actually quite funny. With my dictionary, I'm trying to learn some Chichewa (the national language here) and to establish better contact with the people. I'm glad I'm not alone here, I have a good team here. Together, we went hiking in the adjacent Moulanje Mountains and four of us climbed the highest mountain in central Africa, Mount Sapitwa, which means 'don't go there!' It was very adventurous and exhausting, there are no proper trails, you always walk along the riverbed and when it rains heavily, the paths are impassable. On the way back, we stop at the Old Mans Falls and enjoy the refreshment.

And the hospital? For a medical student, it's incredibly interesting because here you see everything described in the textbooks. People only come to the hospital when it's really bad, so the condition is accordingly. Indolence takes on a new meaning here and death is part of everyday life. The injuries are incredibly serious and it's especially hard to see with the little children and your heart becomes heavy. You feel angry and sad at the same time, you want to help but unfortunately you can't do much. Because the "Clinical Officers" (employees with 3 years of training) may not have had as extensive an education as us students, but they know their field of expertise (pediatrics, men's health, women's health, and maternity ward) quite well. There are currently no doctors at the hospital.

Overall, based on first impressions, I have to say: Malawi is an extremely poor country, which is almost shocking to me how poor it is. But the people here seem to be mostly content, they are very laid-back and extremely friendly! Sure, you get weird looks and I can't stand being called Azungu (white foreigner) anymore, but it's easy to start a conversation and so far, almost everyone has been very nice and open. I'm curious to see what's to come, I'm very grateful for this experience, and I'm really looking forward to exploring the country with Jessi in 3 weeks!

PS: Apologies for the poor quality of the pictures, that's all the internet can handle here.

Abbonate à Newsletter

Rispondi (1)

Simone

Hey Jerry! Schön von Dir zu hören! Die Bilder sind genial! Wir denken an Dich! Viel Kraft und Spaß dir weiterhin!