Wir reisen, also sind wir

vakantio.de/wirreisenalsosindwir

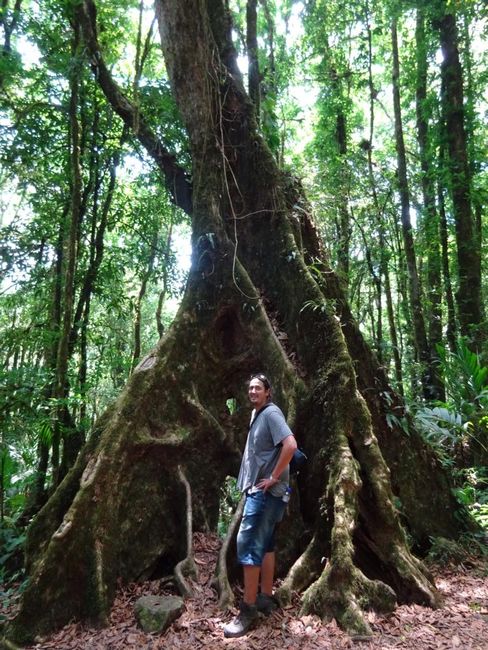

Honduras: Valle de Angeles & La Tigra National Park

Atejade: 01.05.2018

Alabapin si iwe iroyin

We actually went to La Tigra National Park with the hope of catching a glimpse of a Resplendent Quetzal. The Quetzal is the national bird of Guatemala, a colorful bird with long tail feathers and a very shy nature. It takes a lot of luck to see one, and the chances are much better in Honduras than in Guatemala, or so we had read.

So we drove from Danli to the village of Valle de Angeles, which is near the entrance of the park. The village is located on a mountain slope and is quite extensive. It took us a while to find our "hotel," which was located in a secluded residential area in the midst of a steep forested area, and it was not particularly fun to drive on the steep and narrow forest roads. At that time, we even thought we would drive to the park entrance the next day with this car. But we didn't. Thank goodness. Ernesto, our host, said it would be possible to reach the entrance with this car. It hadn't rained. It was just steep, slippery, and narrow. But well, it was dry. Yes, that should work. - That didn't sound very convincing to me, and I didn't feel like finding out halfway up the mountain that the car couldn't make it, only to turn around and go back. So we decided to hire Ernesto and his 4x4 to take us to the park entrance the next day and pick us up later. Thank goodness. We'll come back to that later.

But first, Ernesto invited us to have dinner with him. So we drove down to the village to buy some things and also had the opportunity to take an evening walk through the sweet little town of Valle de Angeles.

Afterwards, we cooked together. We had Anafre, a typical dish from Honduras, which is a fondue made of bean puree and cheese, served with nachos. A special ceramic container is used for this. We had eaten this before and liked it very much. It is usually an appetizer, but with some sausage, Pico de Gallo, and a few beers, we were all more than full.

During dinner, we talked about God, the world, and Honduras. Ernesto is around our age, and he told us that he is actually a mechanical engineer but no longer wants to work in his profession. He bought this (really big and beautiful) house and built two bungalows on the property, which he rents out to guests. He also operates other bungalows in the mountains that he built himself, where he also offers paragliding to tourists in collaboration with a colleague. He even admits that he does all this illegally. In Central America, they live by the motto "It's easier to ask for forgiveness than permission." We had heard this several times before.

Honduras is an incredibly poor country. Even during colonial times, the country was exploited, the Spaniards took the silver, the English took mahogany and other woods. In the 20th century, the country was known as a banana republic, as it was dominated by large U.S. fruit companies at that time. It was discovered that the fertile soils and good climate favored fruit growth and accelerated it. Three large U.S. companies (including the later Dole) acquired large tracts of land for fruit cultivation at a low cost. In 1913, bananas accounted for 66% of Honduras' export business. This not only brought great wealth to foreign banana companies but also gave them extremely great power in Honduras, with politics being dominated by their interests. However, the Hondurans did not benefit much from the wealth generated by bananas. The working conditions were also poor until a two-month strike by 25,000 banana workers in 1954 finally brought about significant improvements. Unions were recognized, and workers gained rights that were unheard of in neighboring Central American countries.

Today, the vast majority of domestic income comes from money sent by emigrated Hondurans in the United States to their families in Honduras. This is not only true for Honduras but also for other Central American countries such as El Salvador. Large agricultural plantations are still owned by foreign companies, although bananas are no longer the most important agricultural product but coffee. Tourism is becoming increasingly important as an economic sector, and according to Ernesto, the call center business is also growing, similar to India. Although steps have been taken towards industrialization, U.S. corporations still dominate the profitable industrial and service sectors, but they create relatively few jobs for locals compared to local small businesses, which account for about 40% of industrial production but employ almost two-thirds of industrial workers.

Ernesto tells us that, in his view, the main reasons for the problems in the country are poverty, lack of education, and fear-mongering. The corrupt government, which is also under the control of the United States, would promote these factors rather than combat them in order to maintain power in the country. About 70% of the population in Honduras is poor. The middle class accounts for about 25%, and 5% are considered rich. As an example, he mentions monoculture, which leads to problems in agriculture here. The land is repeatedly cultivated with the same crops until all the nutrients are depleted and the land becomes barren. When you have to feed your family, you plant what brings the most profit; long-term thinking is difficult with a growling stomach. Furthermore, people are poorly educated, and concepts like crop rotation are not widespread. Or even worse, in the hope of making a quick income, people lease their land at a bargain price to large corporations that then practice ruthless monoculture, make huge profits, and move on when the land is exhausted. The farmers who lose their fertile land in this way have no choice but to move away and seek their fortune in the city. However, since they usually do not have the knowledge or skills to find a decent job there, they end up in the slums on the outskirts of the city, where violence and crime prevail. And so it becomes an eternal cycle of poverty, destruction, and crime.

Ernesto says that it will soon be the same in his village. Sugar cane is mainly grown here, also in monoculture. But the farmers just don't want to listen when you try to give them advice, or they can't because they simply don't have enough to live on. In a few years, the land here will be barren, Ernesto says.

He explains that he is lucky to belong to the middle class. And he sees it as the responsibility of this class to address the problems in the country. The poor people cannot tackle the problems; they are too busy with their own survival, and the rich live in a different world. But the middle class is educated, has resources, and can build something and bring about change. That is the main reason why he no longer wants to be employed and work as an engineer. Instead, he wants to start his own business, build something of his own, so that over time, he can create jobs and help his fellow countrymen.

He tells us that it is a common sight in Honduras for people who come into money to gradually disappear behind thick walls and barbed wire in their beautiful houses because they become afraid of envy. You have to give something back from your own success, otherwise it will never get better for everyone.

I am surprised by how objectively and soberly Ernesto reflects on the situation. It is tough when you see the hardship coming and have to run into it with open eyes simply because you lack the opportunity to change anything. Poverty, lack of education, and fear are bad conditions for the development of a country, and it is difficult to break such a vicious cycle. But I really like his proactive attitude and his willingness to take responsibility, make a difference, and share his success with others. I also think that solidarity is an important key to success; even in Switzerland, the principle of solidarity is an important basis for the prosperity of all. Although at the same time, I struggle with the fact that he has been doing everything illegally so far. It is precisely the taxes that are intended for the common good or at least should be. However, I have to agree that in such corrupt countries, it is somehow understandable that people try to bypass the tax authorities because the hard-earned money of the people disappears without a trace instead of being used to improve their living conditions.

We talked late into the night, and the next day, we had to make our way back to Tegucigalpa to return the rental car, so we said goodbye to Ernesto and set off.

Alabapin si iwe iroyin

Idahun

Awọn ijabọ irin-ajo Honduras