The never-ending walnut harvest

Atejade: 12.07.2020

Alabapin si iwe iroyin

Swansea is a small town on the east coast of Tasmania. It is located in the northwest of the Great Oyster Bay, across from the Freycinet National Park. Swansea was the first urban settlement to be established after the founding of Sydney and Hobart. In this small coastal town, Webster, a walnut company, has expanded over 80 hectares. By the way, the company's headquarters are located in Leeton, New South Wales.

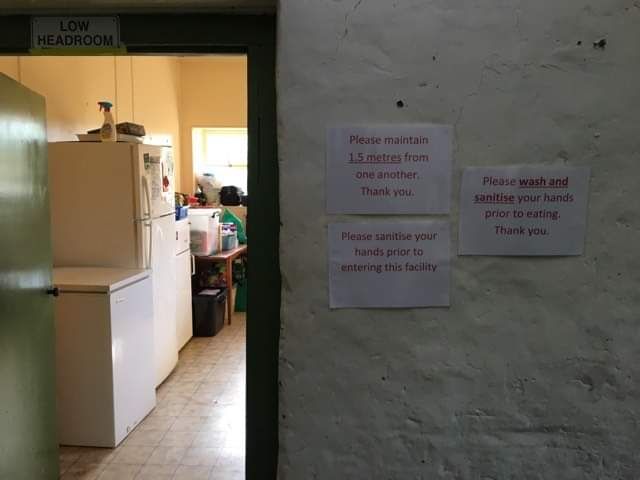

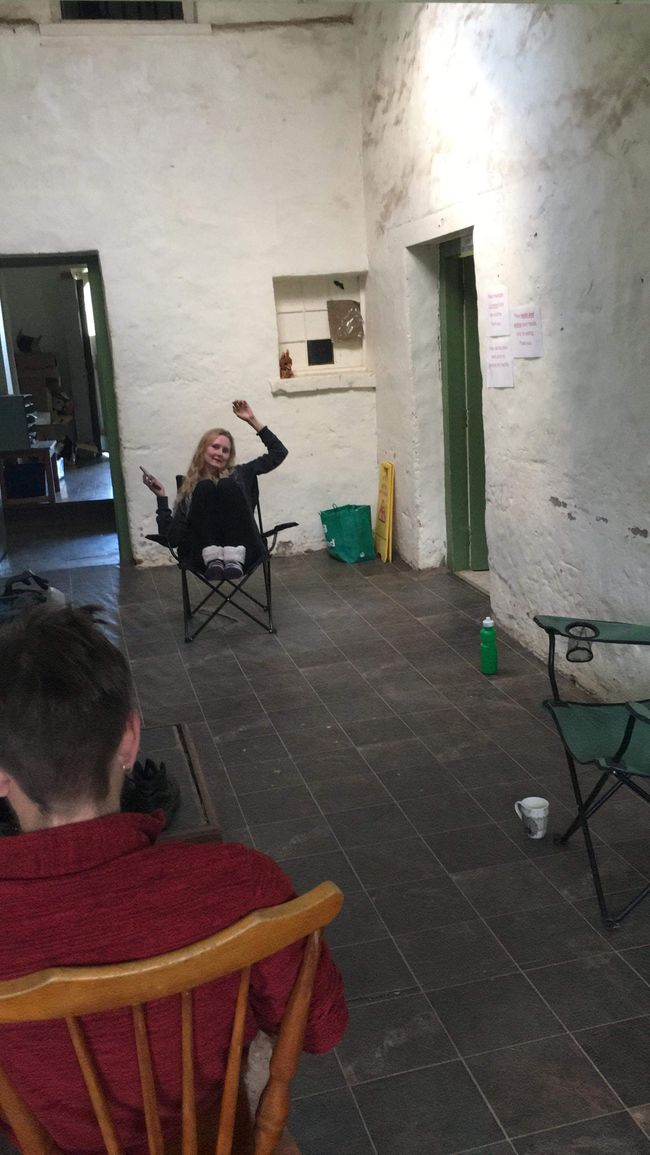

Due to heavy rain that causes many floods, we are forced to take a break for five days. The mood among the backpackers is slowly shifting. After all, we are not here to go on vacation, and to make matters worse, Covid-19 is slowly creeping in. Our manager, a small man with a lot of energy who always wants everything to go smoothly, seems to enjoy enforcing all the corona guidelines. One morning, he gathers all of us together to explain the new rules. He wants us to no longer leave the farm unless we need to buy groceries at the small store in Swansea. Usually, we would take the long trip to Launceston to do the shopping for the next two weeks, as it is actually cheaper to drive the 300 km instead of stocking up on groceries in the small, expensive store. Then he talks at length about hygiene, how, when, and how often to wash our hands properly. We have to keep 1.5 meters apart - even in our small kitchen, which we have to share between eight of us. Next, we are supposed to pick our own dishes and, of course, only use those, which does not apply to pots and baking sheets... Work can slowly resume. New rules are introduced at the hulling line, mainly concerning social distancing. Only one person is allowed to work at the inspection table, and the rock tank, for example, can only be cleaned by one person. For our breaks, two 15-minute breaks and one half-hour break, the entire hulling line is shut down, and we are no longer allowed to switch positions during a shift. It feels like more and more is being demanded of us, and our well-being is given little consideration. A few days later, after we have just come to terms with it, the more stringent rules are explained to us in the next long conversation. From now on, we must maintain a distance of 1.5 meters outside and four meters inside. Before starting work, our temperature is taken daily, and anyone with a temperature above 37°C is not allowed to work. And finally, we are told that we have to carry the sofas out of the "living room" and replace them with camping chairs. This is how our manager wants to make sure that we also maintain the four-meter distance. The mood on-site is getting worse and worse. There is a lot of talking, and unfriendly things are being said. Now, in hindsight, I can understand the situation much better, and it is not so difficult for me to deal with it anymore, but at that moment I was very angry and disappointed. After all, I have been working twelve hours every night, and now I can't even relax on the couch?! We all felt personally attacked, but of course, I also know that our manager has responsibility for us, and he works for a big company. If Corona were to break out here, they would probably suffer millions in losses. Nevertheless, we continue to work diligently, and I try to focus on other things. As the next low point, there is a misunderstanding about a broken lamp. One of the backpackers broke the light in the room and now wants to replace it with a new lightbulb and holder. So, he turns off the power to the house and starts replacing the lightbulb, but when the manager finds out, he is furious and tells us to keep our hands off the electricity. So, we sit in the evening, without light, on our camping chairs around the fire and vent our frustrations. At the same time, our manager is still working at the hulling line because there is still something to be repaired. Later in the evening, he comes into the house and sees us all sitting close together. I can see that he is tired and resigned. He calmly informs us that we all have to leave the farm the next day and find accommodation elsewhere. We are angry and lost at first, where can we find accommodation so quickly in these times of Corona? The next day, everything feels completely different. We can move into the backpacker hostel in Swansea, which is only ten kilometers away from the farm. After venting all my frustration, I feel much better. I accept being kicked out and can slowly see the advantages. Flo and I move from a tent to a private room, there are enough sofas for everyone and a TV. Since there are only three other women in the hostel with us, it is always quiet, and I finally manage to sleep for more than four hours during the day. After a few days, we are all satisfied with the change of scenery. After all the trouble, I focus on my work again. The same questions before each shift: How are you? No cough, sore throat, sneezing, or runny nose? Not tired? Then the temperature is taken, and then we are allowed to go to the hulling line. For twelve hours, I stand at the inspection table or at the waste belt - I alternate shifts with Hugo (the French guy). The highlights are always the ten to fifteen minutes during which we change field or fan containers. Twelve hours with myself. Twelve hours in my head with my thoughts. The same songs, even the same verses, play over and over again, and sometimes I can't get rid of them. "Ohhh Panama" (AnnenMayKantereit - Jenny Jenny). They keep tearing through my thoughts, again and again, and sometimes I can't get rid of them. After two years, she was there for ten minutes. Oh Oh Oh Panama!" Hours later, the spider suddenly stands in front of me again! She must have been hiding from me for half the night, probably observing me closely! She smiles mischievously at me, and outside the sun slowly rises. After a few hours of sleep, a quick meal, and then it's back to the farm. "How are you? No cough, sore throat, sneezing, or runny nose? You're not tired?"

Most of the time, I choose a topic to think about specifically. For hours. It starts with "what could I cook?" and usually turns into dreams: "How do I want to live one day?

Due to heavy rain that causes many floods, we are forced to take a break for five days. The mood among the backpackers is slowly shifting. After all, we are not here to go on vacation, and to make matters worse, Covid-19 is slowly creeping in. Our manager, a small man with a lot of energy who always wants everything to go smoothly, seems to enjoy enforcing all the corona guidelines. One morning, he gathers all of us together to explain the new rules. He wants us to no longer leave the farm unless we need to buy groceries at the small store in Swansea. Usually, we would take the long trip to Launceston to do the shopping for the next two weeks, as it is actually cheaper to drive the 300 km instead of stocking up on groceries in the small, expensive store. Then he talks at length about hygiene, how, when, and how often to wash our hands properly. We have to keep 1.5 meters apart - even in our small kitchen, which we have to share between eight of us. Next, we are supposed to pick our own dishes and, of course, only use those, which does not apply to pots and baking sheets... Work can slowly resume. New rules are introduced at the hulling line, mainly concerning social distancing. Only one person is allowed to work at the inspection table, and the rock tank, for example, can only be cleaned by one person. For our breaks, two 15-minute breaks and one half-hour break, the entire hulling line is shut down, and we are no longer allowed to switch positions during a shift. It feels like more and more is being demanded of us, and our well-being is given little consideration. A few days later, after we have just come to terms with it, the more stringent rules are explained to us in the next long conversation. From now on, we must maintain a distance of 1.5 meters outside and four meters inside. Before starting work, our temperature is taken daily, and anyone with a temperature above 37°C is not allowed to work. And finally, we are told that we have to carry the sofas out of the "living room" and replace them with camping chairs. This is how our manager wants to make sure that we also maintain the four-meter distance. The mood on-site is getting worse and worse. There is a lot of talking, and unfriendly things are being said. Now, in hindsight, I can understand the situation much better, and it is not so difficult for me to deal with it anymore, but at that moment I was very angry and disappointed. After all, I have been working twelve hours every night, and now I can't even relax on the couch?! We all felt personally attacked, but of course, I also know that our manager has responsibility for us, and he works for a big company. If Corona were to break out here, they would probably suffer millions in losses. Nevertheless, we continue to work diligently, and I try to focus on other things. As the next low point, there is a misunderstanding about a broken lamp. One of the backpackers broke the light in the room and now wants to replace it with a new lightbulb and holder. So, he turns off the power to the house and starts replacing the lightbulb, but when the manager finds out, he is furious and tells us to keep our hands off the electricity. So, we sit in the evening, without light, on our camping chairs around the fire and vent our frustrations. At the same time, our manager is still working at the hulling line because there is still something to be repaired. Later in the evening, he comes into the house and sees us all sitting close together. I can see that he is tired and resigned. He calmly informs us that we all have to leave the farm the next day and find accommodation elsewhere. We are angry and lost at first, where can we find accommodation so quickly in these times of Corona? The next day, everything feels completely different. We can move into the backpacker hostel in Swansea, which is only ten kilometers away from the farm. After venting all my frustration, I feel much better. I accept being kicked out and can slowly see the advantages. Flo and I move from a tent to a private room, there are enough sofas for everyone and a TV. Since there are only three other women in the hostel with us, it is always quiet, and I finally manage to sleep for more than four hours during the day. After a few days, we are all satisfied with the change of scenery. After all the trouble, I focus on my work again. The same questions before each shift: How are you? No cough, sore throat, sneezing, or runny nose? Not tired? Then the temperature is taken, and then we are allowed to go to the hulling line. For twelve hours, I stand at the inspection table or at the waste belt - I alternate shifts with Hugo (the French guy). The highlights are always the ten to fifteen minutes during which we change field or fan containers. Twelve hours with myself. Twelve hours in my head with my thoughts. The same songs, even the same verses, play over and over again, and sometimes I can't get rid of them. "Ohhh Panama" (AnnenMayKantereit - Jenny Jenny). They keep tearing through my thoughts, again and again, and sometimes I can't get rid of them. After two years, she was there for ten minutes. Oh Oh Oh Panama!" Hours later, the spider suddenly stands in front of me again! She must have been hiding from me for half the night, probably observing me closely! She smiles mischievously at me, and outside the sun slowly rises. After a few hours of sleep, a quick meal, and then it's back to the farm. "How are you? No cough, sore throat, sneezing, or runny nose? You're not tired?"

Most of the time, I choose a topic to think about specifically. For hours. It starts with "what could I cook?" and usually turns into dreams: "How do I want to live one day?

Alabapin si iwe iroyin

Idahun

Awọn ijabọ irin-ajo Australia