Writing, reading, doctoral thesis and next to it, afterwards and right in the middle of it all, the Rocky Mountains. Or: Do it!

Басылган: 04.09.2023

Бюллетеньгә язылу

Apparently, a “foreword” seems to be established for me in texts about which I am unsure. Some of my blog posts go through a “review process” and some are proofread. Also the following text.

“I think I understand why you think the lyrics seem somehow stupid or strange. I liked it when I read it. (...) I know you and know what you mean.

But others may read the text differently. They will feel proselytized, they may think you are arrogant, they will think the text sounds defiant and then again like a defense.

Maybe some people will pity you and say that the woman is restless and has a problem.

But many people will also read it the way you want it: namely as an encouragement to dare to do something.”

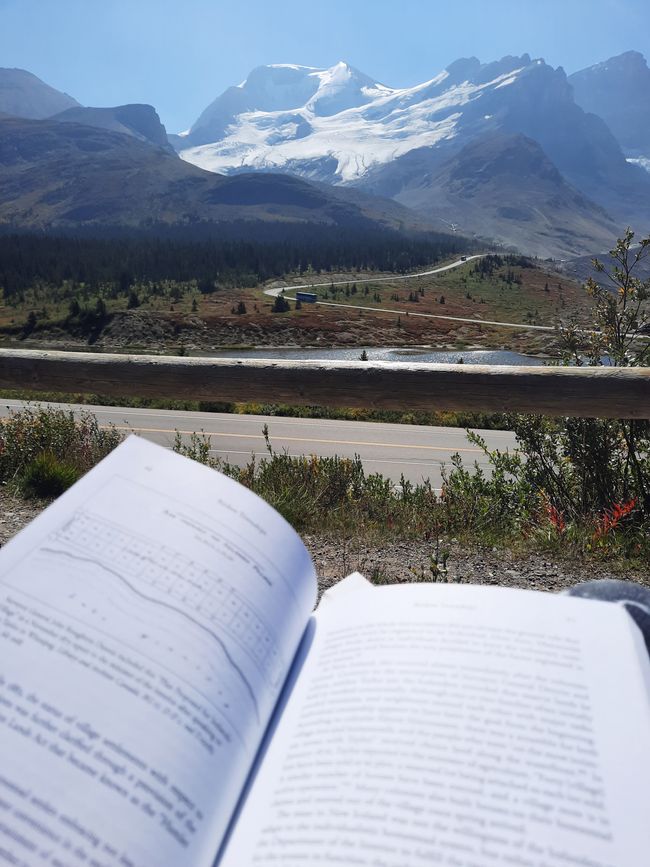

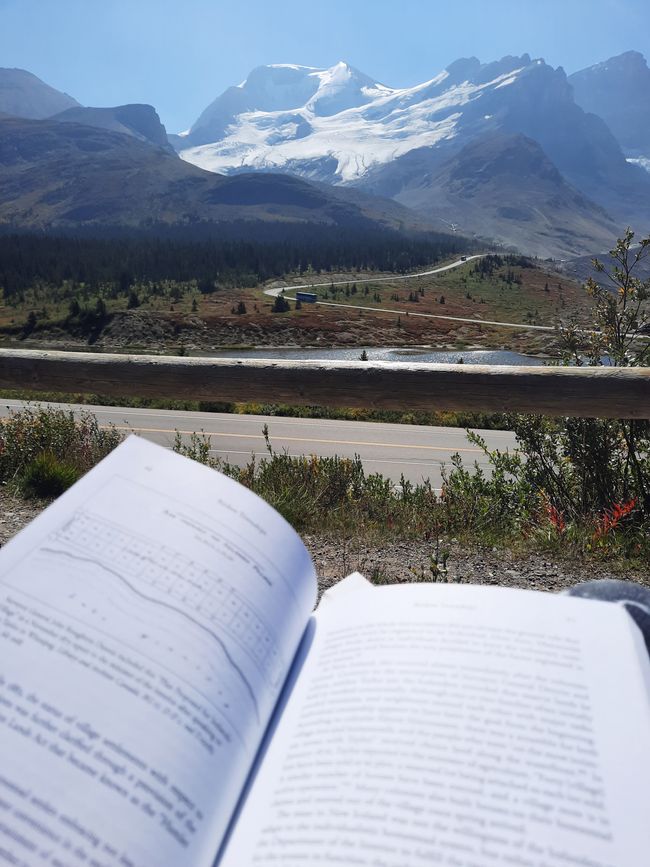

So I first thought about reworking the text, at least “softening it” a little, then I had the idea of leaving it alone. And then decided to just leave it like that; just as I wrote it with a view of the glaciers from the Columbia Icefield and perhaps drunk with happiness.

In the bed next to me is Leanne from London - who is currently doing a research stay in Canada for about three months. She works for a social enterprise that wants to bring nature and wildlife back to cities ( @we_are_wilder ). Leanne also took the train from Toronto. When I tell her what I'm doing, she's really excited: "You definitely have to talk to Kai!" Kai sleeps in the bed above me; and will be in Australia for a fellowship from January.

To everything: No kidding, no joke. That is real. And I'm in the Rocky Mountains for a few days, combining work and travel and I'm not the only one in the hostel in Lake Louise who not only spends the day in the mountains, but also opens my laptop.

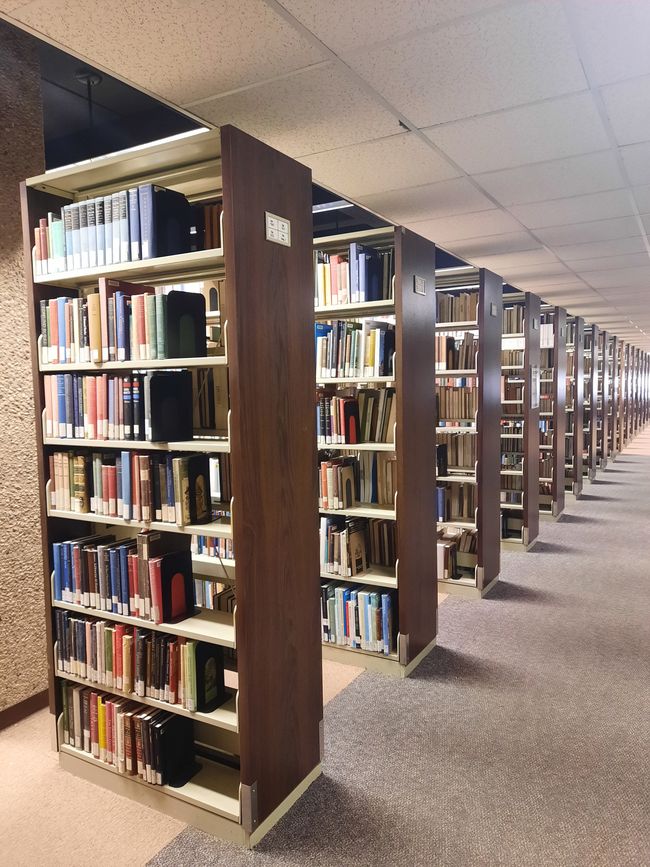

After over 30 archive boxes, hours of mostly Ukrainian-language contemporary witness interviews, many meetings and conversations as well as days in the library in Edmonton (known, among other things, for its focus on Ukraine), I have a somewhat unusual backpacker life ahead of me for some time:

on the one hand hostel, carpooling (for Canada Poparide ), especially pasta with tomato sauce, granola bars, shared rooms. - I am reminded of myself about 15 to 20 years ago.

On the other hand, I also took time every day to read and write for my doctoral thesis.

"I can't imagine that!" or alternatively: " That doesn't work! You have to sit quietly at your desk for something like that." or - I've also had it: " Sarah, you always think you have two lives." I heard this recently about some of my projects in my German life, before the trip and more often in the last few years. It was and is difficult for me to remain patient with such comments because I am firmly convinced that they are nonsense.

Yes, writing a doctoral thesis is a lot of work and can sometimes be overwhelming. Every now and then there is the feeling that you are not doing enough, that everything is pointless, that everything is worthless. Here, too, I am firmly convinced that this is not the purpose of such an undertaking - and I like to say that (to myself) before I'm finished. (Perhaps also exciting for some people: the podcast: get your doctorate happily.)

If I do a doctorate, then do it in such a way that I don't lose interest in it. My intention since the first idea. And a topic that literally opens up the world to me.

I once heard that the process and especially the completion of a doctoral thesis could be compared to a hike. You start enthusiastically, at some point you're knocked out, you get lost, you forget something, you turn around, take a break and basically it's about not giving up shortly before the finish. Above all, as always in life, it's about enjoying the journey. And that's exactly what I planned to do.

And so far I can say: that's how it is, that's how I do it. I don't know why I shouldn't do that either.

So hostels for a few days, be outside, hike and work on your laptop in the most beautiful surroundings. This is exactly what I imagined.

I have more than enough material for translating and evaluating and I find it ideal, even fantastic, that the breathtaking landscape takes me away from the computer for half a day at a time.

Especially in the morning and afternoon it is quiet in the hostels in the Rocky Mountains, at least from what I experienced; Most of them are in the national parks, so I have peace and quiet there. The hostels here are not party accommodation. From 11 p.m. onwards at the latest it is as quiet as a mouse, actually before then.

I have my work schedule and am good at sticking to it. I've never really lacked discipline or motivation. Maybe I'm very blessed there. It helps me to plan and implement tasks (whether on the road or in Germany) using 'timeboxing'. If you want to know more about this, I recommend @Dr. Martin Krengel or here: https://www.studienstrategie.de/anpack/ .

On the subject of motivation: it sounds cliché, but if you do exactly what you want to do and what you enjoy and are passionate about, there is almost never a lack of energy and work, above all, doesn't feel like work. For me that's true. What also helps and probably the most: rewarding yourself for tasks.

For me it's being right here; Hiking, taking the train every now and then. There is also another tip that helps (me): by tackling tasks that are demanding - in some cases overwhelming - such as deciphering Ukrainian manuscripts from the 1940s or producing good texts, in places that are familiar to me really liked it. So even later work on these texts, which is sometimes not so much fun (footnotes, formatting, reworking and revising, etc.), is associated with positive feelings about the creation process. I don't know where I got this from, but since I realized this years ago, I've been able to work very well and get into a flow, into a state of great concentration, when I travel. This means that raw texts are created quickly for me.

Now I'm far from finished and, above all, I still have a lot to analyze, translate and write, but I have the impression that it's going well, even very well. And so I say with a very mischievous smile on my lips: “ Guys, it works! You just have to want it and imagine it first."

There are a lot of people - always! - on your own path, who tell you very intensively what wouldn't work. I had this when it came to jobs and promotions; on the subject, I went to New Zealand for a year as an East German village child without much money when I was just 19; I had that before my current tour.

And I have the impression that women hear or feel this much more often than their male counterparts.

I've talked about this more recently with fellow travelers. From England to Singapore and Munich and different genders: Men obviously hardly hear that what men are planning is “unrealistic”, “unrealistic”, “unworldly”; For women, such a project is seen as “abnormal”, some also hear “Oh, you’re brave,” which is meant to be somewhat positive, but it’s different with a skeptical “Why?” or a list of possible dangers including persistent questions : “And after that?” Some people probably also hear “Well, you just don’t have a husband” or, behind closed doors , “She just didn’t get one.” There are certainly men who are viewed with skepticism, but there were none in my non-representative survey. They were rather surprised to notice how differently - and in their case positively - those around them reacted to unusual (travel) plans compared to women traveling alone.

Not letting others' skepticism and lack of imagination dissuade you is probably what I've learned the most and I tell everyone from the bottom of my heart: if you can imagine it, then go for it.

No matter how crazy it seems to others or what is said: make it happen!

Stop comparing yourself (important!),

but ask around how it can work.

Talk to people about what you would like to do and achieve

and listen to those who give you tips and advice, who celebrate you for your ideas, who help you overcome fears and concerns and thus enable you to push the boundaries of your own comfort zone. There is nothing better!

This experience and this feeling of self-efficacy makes me personally incredibly happy. The only dangerous thing about it: it is addictive in a very positive sense.

Money certainly plays a role in my version of being on the road and working, see blog entry no. 1. The main challenge is to find a way to finance it and to really start looking first.

In recent years there have been more and more reports about digital nomads, people without a permanent address who only travel and work digitally. I think Fabian Hilpert ( @fabitravel ), albeit in a completely different area and traveling differently, fully inspired me in Minsk in 2019. How excited I was, and still am, by this idea.

Savings are definitely important for my venture, because Canada is expensive - as is Australia - and without question the scholarship gives me enormous freedom and a degree of security. This is a privilege and it often feels like winning the lottery - it is somehow a winning the lottery in the field of (training) education. I appreciate that. - It should be noted that many foundations often complain that, despite everything, too few people apply - this is a side note.

What also gives you at least a little bit of pocket money: invest in ETFs (and start long before the trip and then choose which one has a high payout, for example per quarter).

The main thing is to set the costs in Germany to 0 as far as possible. If you are abroad for a longer period of time, you do not need health insurance in Germany. This saves around 300 to 400 euros per month if you had to take out private insurance. This is the best tip I've read on a travel forum anywhere. International health insurance for one year costs a total of around 400 euros. Knowing this brings huge monthly savings. (The only catch: returning to Germany for a short time is not that easy: in Germany there is compulsory insurance and international health insurance (of course) does not apply there. If you return in the meantime, it is a bit complicated to get back to the health insurance company for a short time logging in and then logging out again, whether you can pause again afterwards is probably not always entirely clear.)

I sublet my room in Hamburg; I previously lived in a shared apartment anyway. I don't have a car (anymore) and started thinking about every purchase and expense about two to three years before the trip; whether I really need it or could take it with me somewhere. A bit like “The big five for life”.

If you are abroad for a longer period of time, you can easily leave your cell phone contract on hold during this period so that you don't pay monthly for what you don't need anyway.

Hiking itself is also a hobby that doesn't cost a lot of money. Good as well.

In the very expensive and touristy areas, it will just be a bed in a shared room. The Rocky Mountains are breathtakingly beautiful and the prices are breathtakingly high. In my opinion, hostel life is totally ok for a while, especially since even a place to sleep in a shared room costs the equivalent of around 50 or 60 euros per night.

At my mid-30s, I'm far from being the oldest in the hostel, but I'm also no longer the youngest. I also notice that I no longer seek contact as intensively as I did at the beginning of my “hostel career” when I was 16 or 17. The slightly older people, who are also often traveling alone, are exciting personalities and it's great fun to be surrounded by them. So I can have a hostel room for a few days and I can sleep almost anywhere anyway - I'm very blessed in that regard too.

And that means I'll be offline for the next two weeks or so and really (only) have a vacation, without a laptop, electricity, network, internet and instead with the tent. Next time it will be about the West Coast Trail , nine days on the Pacific, along the coast of Vancouver Island.

Бюллетеньгә язылу

.Авап (2)

Erika

Erika

Hallo Sarah,

zunächst möchte ich dir sagen, dass mich deine Art zu schreiben schon bei den ersten Sätzen "geflasht" hat. Da ist jemand mit tiefgründigen Gedanken, der die Welt in vielen Facetten sieht und sich Zeit nimmt, genauer hinzuschauen, jemand der offen ist für alles was kommt und sich auf die nächste Herausforderung freut. Es tut so gut, deinen Blog zu lesen, weil solche (deine) Gedanken viel zu wenig zu hören/lesen sind.

Aber mir sprichst du aus der Seele. Schon als kleines Kind hatte ich den Wunsch, jeden Flecken auf unserer Erde kennenzulernen. Aber da wusste ich schon, dass ein Menschenleben leider nicht dafür ausreichen würde.

Aus familiären Gründen konnte ich erst mit fast 60 Jahren das umsetzen, was ich schon immer wollte: alleine reisen, um mir Zeit nehmen zu können für das, was mir wichtig ist und es mit allen Sinnen genießen. Und so war ich jeweils 4 Wochen in den Pyrenäen und auch im Nordwesten der USA und Kanada unterwegs. Allerdings recht komfortabel mit Motels und Auto (was auch mit gesundheitlichen Einschränkungen zu tun hat).

Ich habe diese Wochen so sehr genossen, sie hätten ewig so weiter gehen können ... ich hab mich vorher noch nie so frei gefühlt, fand, dass ich die Eindrücke um mich herum viel intensiver aufnahm - da waren so viele glückliche Momente! Die Lust darauf Neues zu entdecken, neue Erfahrungen zu machen hat mich jeden Tag begleitet ... ein Gefühl wie Heimweh ... nur in die andere Richtung!

Was für mich auch wichtig war: die Erkenntnis, auf meine Intuition vertrauen zu können und spüren, mit mir selber gut klar zu kommen.

Und "natürlich" reagierte mein engeres Umfeld, wie aber auch viele Menschen unterwegs so, wie du es auch erlebst: teils mit Unverständnis (weil: alleine als Frau = unvernünftig), teils mit Bewunderung, dass man sich "so was" traut...

Ich bin jedenfalls froh, dich etwas "kennengelernt" zu haben und wünsche dir: bleib wie du bist und zeige weiterhin allen Menschen, denen du begegnest, wie gut es ist und tut, "open minded" durch die Welt zu gehen.

Liebe Grüße

ErikaSarah

Liebe Erika, vielen herzlichen Dank für diese sehr liebe Nachricht! Es hat mich wirklich sehr gefreut Deinen Kommentar zu lesen, der mich nun bereits in Sydney erreichte. :)

Wie schön, was Du von Deinem Weg und Deinen Reisen berichtest! Das freut mich sehr und hört sich sehr gut an! "... ein Gefühl wie Heimweh ... nur in die andere Richtung!" - absolut und sehr schön beschrieben!!!

Somit: ein großes Dankeschön für die sehr lieben Worte und alles Gute! Sollte es von Dir ebenfalls hier einen Blog geben, verlinke ihn gern. :)

Sarah

Сәяхәт отчетлары Канада