Mit Geschichte(n) um die Welt

vakantio.de/mitgeschichteumdiewelt

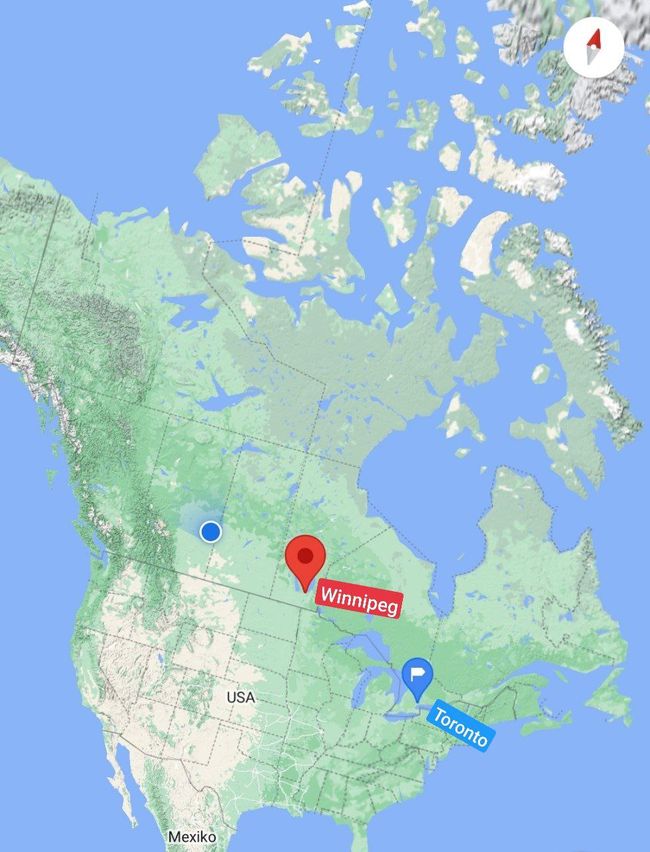

Back on/on the train! A road to Edmonton through the prairies

E phatlaladitšwe: 29.08.2023

Ingwadiše go Lengwalo la Ditaba

It's the vastness that fascinates me. The full nothing to the horizon.

It's like sea without water; an area, seemingly without end, as far as the eye can see.

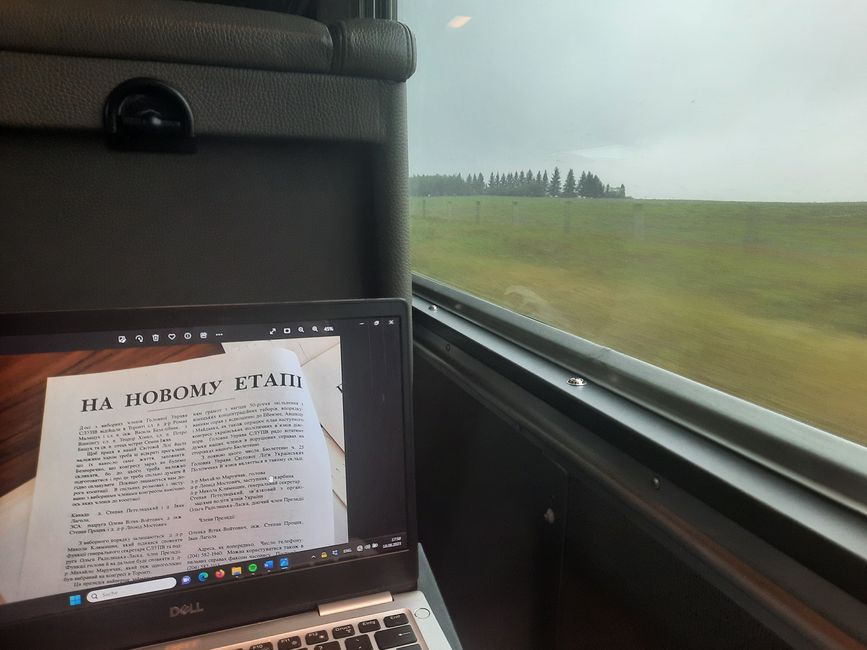

Again no cell phone reception, no internet, but a seat in the Skyliner, on the fully glazed second floor of the on-board bistro. But this time the landscape outside the window is different.

The Winnipeg-Edmonton route is more than 1,300 kilometers and leads past fields, meadows and fallow land;

a few bushes,

a few smaller lakes, rivers;

fields again,

Clusters of trees, often birches.

Mainly gravel roads.

There are a few hills, that's it.

Somehow the landscape reminds me of Silesia/Sląsk or even more of Ukraine and Belarus. I also wanted to write Uckermark first, but the fields there are too uniform and too much cultivated. There are also monocultures and huge cornfields without any sign of weeds or wild growth here, but there are also always huge, rather uncultivated areas in between. The latter is rarely seen in Germany, a little more in Poland and even more frequently further east in Europe. I have (and often had) the feeling that there is much more life, nature, diversity there; Not everything seems (is?) fixed and prefabricated and somehow enclosed like on German fields. Somehow I felt the rather untouched nature and thus wild growth and fallow land as freedom.

But as the day progressed, I noticed that this seemingly somewhat more unspoiled state seems to be more of a fallacy: cultivating the land here is enormous work, massive machines are used to till the fields; Farm planes 'explore' the crop and/or fertilizer. You rarely see towns. From Alberta, the next province and further west, the landscape changes a bit. It's getting hillier, there's more civilization again, towns are closer together again.

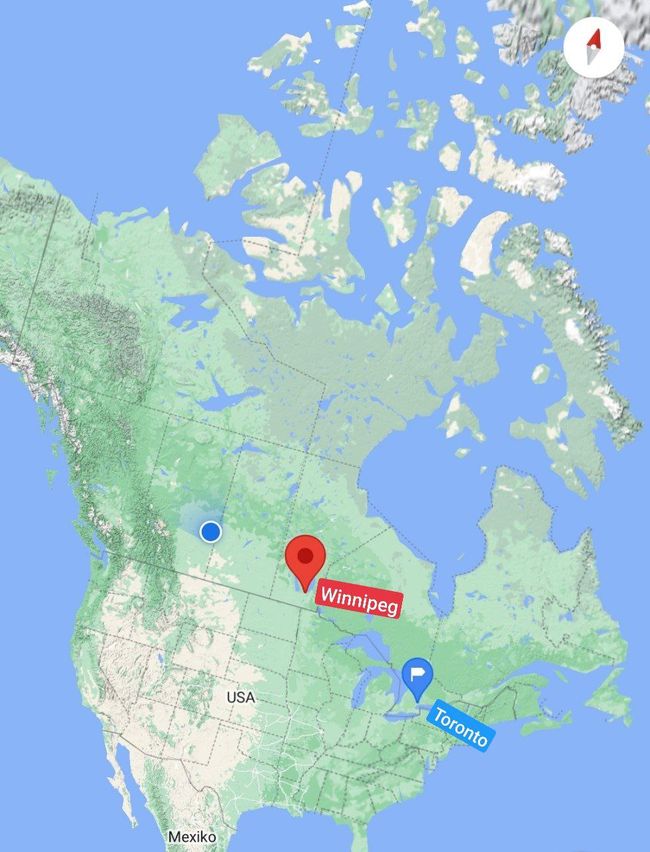

For the way to the second closest city from Winnipeg, after Edmonton, I of course take the train again. This takes a while. About 24 hours.

Those distances! I am and have always been fascinated by maps and globes. So I know that Canada is very big. The experience, however, is something else. Now I really believe it too. That's a huge area, this Canada. The maps appear to be correct.

The landscape here has changed enormously since the colonization and I often wonder what it might have looked like 200, 300 years ago; I have in mind the replicas from the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg on prairies. No excessive vegetation, but plants with enormous root sizes in the ground. Bison herds, birds, insects without end, also huge colorful butterflies.

Even for me, the distances are long today and hardly any Canadian would seriously consider taking the train for this journey.

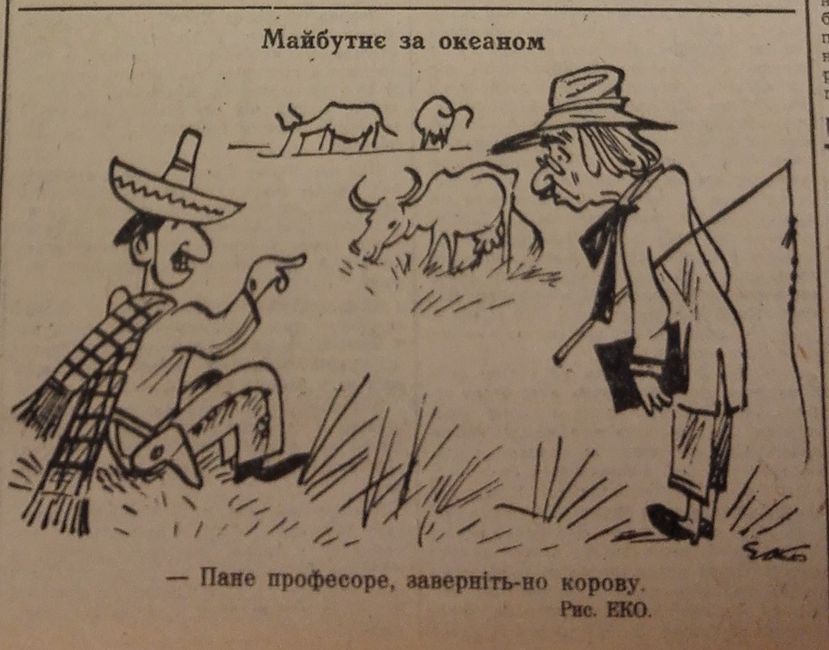

The agricultural areas of Manitoba and Saskatchewan in particular were regions in which people from Eastern Europe settled, who also colonized the areas. People of all religions from Poland, Ukraine, Soviet Union. They came to this country mainly from the end of the 19th century and also after the Second World War.

The journey to these areas must have been overwhelming. What a long way!

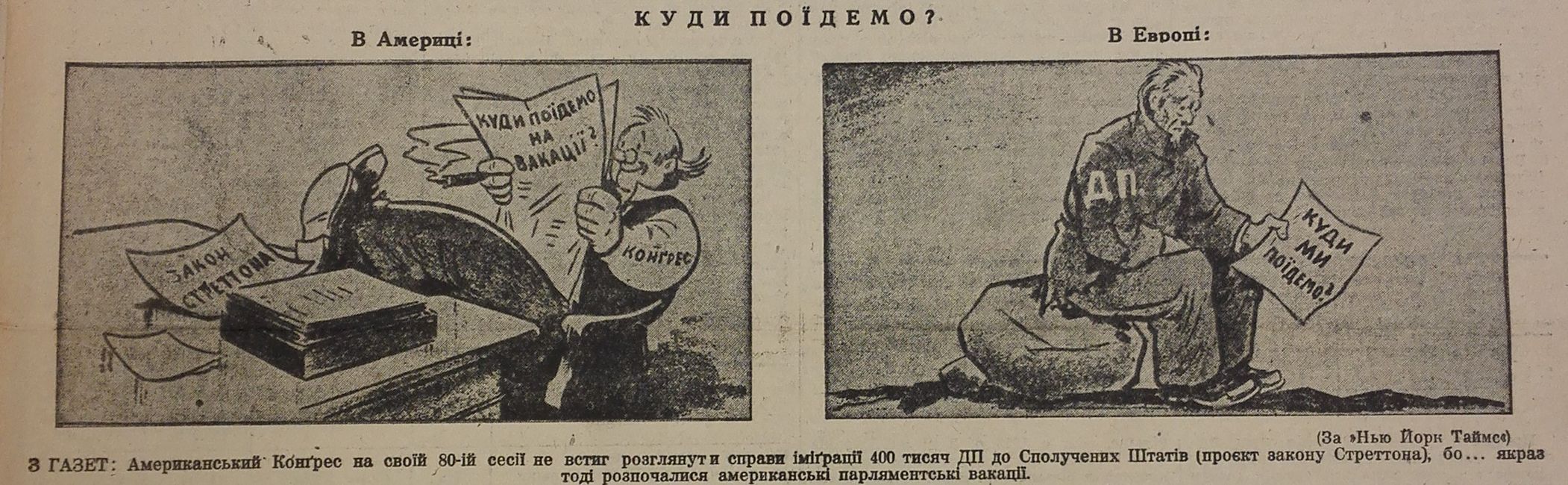

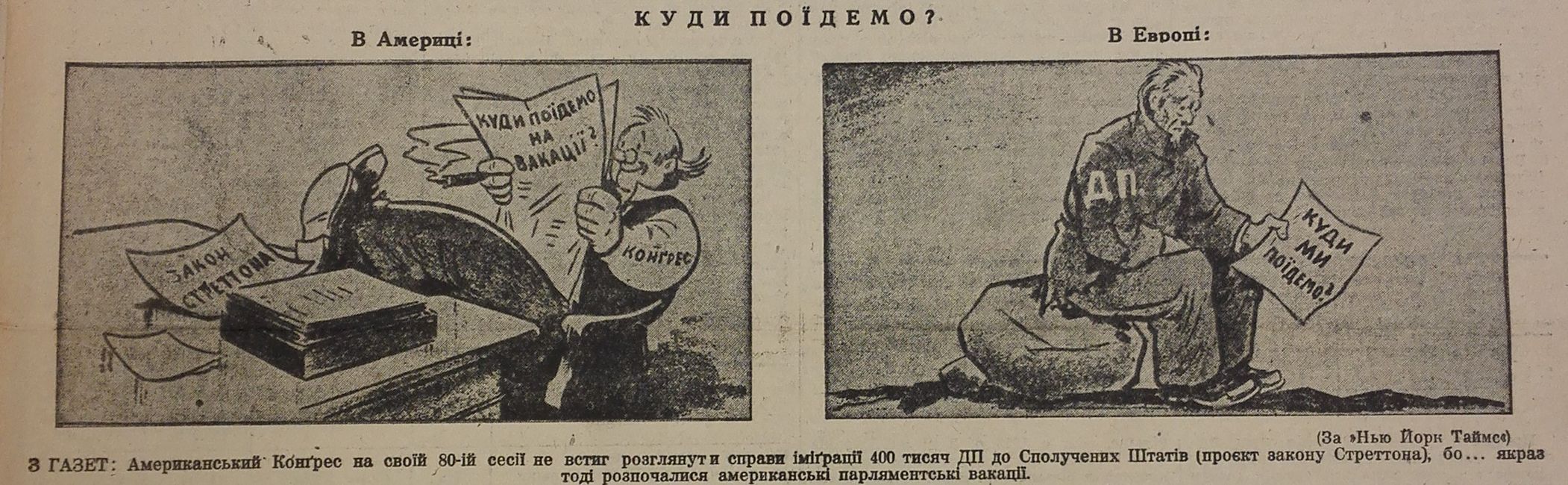

Most of the people who immigrated as displaced persons came after 1948, and many later. After years in DP camps in the western zones of occupation in German-speaking countries, they usually went to Bremerhaven for a few weeks. This was arguably the most important port for those heading to North America.

They had already cleared one difficult hurdle: they had a visa.

The USA was the dream for many, although Canada was initially less well known, it was (compared to other countries!) quicker to open the doors to certain immigrant groups.

Above all, the "old" Ukrainian diaspora in Canada supported the Ukrainian DPs. Around 30,000 to 40,000 Ukrainians immigrated to Canada as "newcomers" from the late 1940s.

Well over a hundred thousand Polish citizens fought on the British and American sides during the Second World War. Many of these former soldiers initially stayed in Europe. For them, too, the question arose as to where they should go, because for many, returning to communist Poland or the Soviet Union was completely out of the question. Many of these former Polish soldiers on the Western Allies later emigrated to Canada. (Canada is part of the British Commonwealth.)

The IRO, the International Refugee Organization, an internationally supported organization for the support of refugees and those who had become homeless, took over the crossing to a new country of emigration, no matter where. The IRO mainly organized their emigration from Europe. An enormous undertaking: Between 1947 and 1951, the IRO helped more than a million people, former DPs, to emigrate.

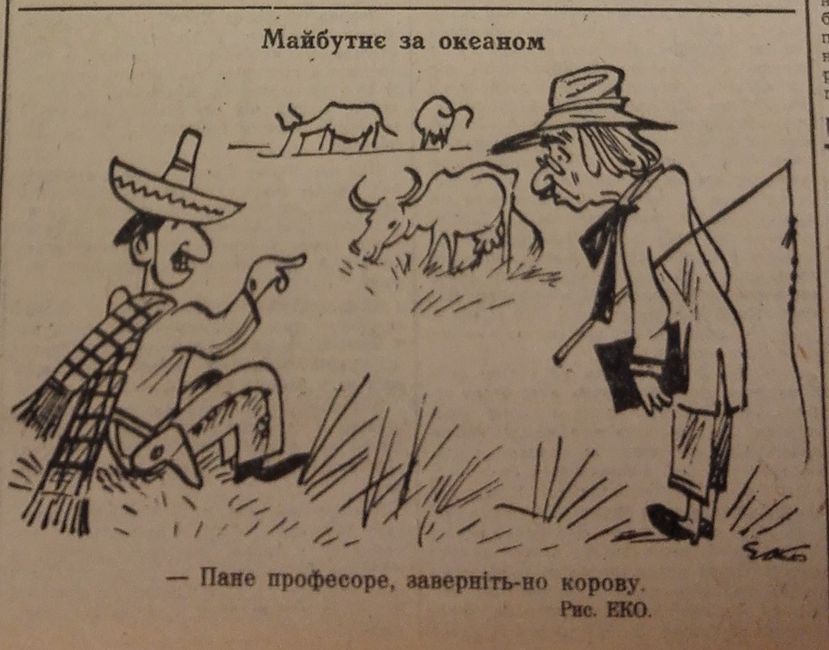

The host countries themselves decided who was allowed to come to the respective country of emigration. Young, healthy people, couples with few children, Christian Europeans and those who had jobs that were needed in the respective countries were particularly popular.

Some were wise enough to simply state these professions. In many cases, religious communities also helped to obtain visas. Quite a few realized that declaring a (different) faith community, eg Orthodox instead of Catholic or vice versa, could be the way to emigrate more quickly since there was support at a certain point in time. The same can be seen with ethnic information, these groups also support their respective compatriots in arriving and getting on. In any case, the people came from ethnically and religiously very mixed regions of origin in Eastern Europe. For many, it was difficult - especially from an administrative point of view - to clearly define a group membership. (Cf. my blog post on Belarusian London )

Canada as a country with a lot of space, far away from devastated Europe and above all with a need for labor in agriculture was considered attractive. It became more and more the dream country of many European emigrants.

Displaced persons who had all the documents, health checks, vaccinations, etc. behind them mostly came by train to Bremen-Grohn (a district of Bremen in the north), where there was another health check. Anyone who was considered healthy was allowed to board a ship to North America about two weeks later.

The ship reached the port for landing in Halifax, Canada, after around 12 to 14 days. After further health and document checks, the newly arrived immigrants traveled to their respective destinations, primarily by train. A trip back then to Manitoba or Saskatchewan would probably have lasted about a week. They probably took the same route to the west as today's train no. 1, the same one I take.

What was going through the minds of these 'New Immigrants' on the way back then?

Was it more curiosity and relief or melancholy and longing for home, even though there hasn't been a home for years?

Especially for the Ukrainian diaspora in Canada it is well known that after a short time there was enormous tension between the old and new immigrants. Entire books have been written about it. There is also a lot about Polish immigration. These investigations are often limited to the respective groups. Often the authors of these studies are and were themselves part of the respective community. Encounters with each other with other ethnic or religious groups or even indigenous people are rarely or not at all illuminated, at least as far as I can see. Are there any sources for this? Or the perspective? Or both?

In Winnipeg I tried to follow that up. Two busy people who I look at more closely in my work, one who saw himself as a Pole, the other as a Ukrainian, emigrated here at almost the same time. Both survived various German concentration camps. The two probably met more than once in Bavaria. Both lived and worked - if the addresses I have are correct - 1.2 miles apart in the 1970s/80s. The journey takes less than 20 minutes on foot and just six minutes by bike. Their churches - one went to the Roman Catholic, the other to the Ukrainian Catholic - are less than 1.4 kilometers apart.

Coincidence?

Don't you just cross paths sometimes? Walking, shopping, whatever? I don't think it's unlikely that both of them would meet again later. I couldn't find anything about it in the many archive boxes and when I first looked through the materials. Maybe there would be something in the many(!) other boxes that were neither numbered, indexed nor ever evaluated by anyone? And some social contacts are difficult to prove through written sources. At the beginning of the 2000s you could have asked at least one of them. Today, more than 20 years later, the question can hardly be answered.

I found it interesting that my questions in this regard aroused interest in one community as well as in the other, but I rather heard that the connections between the respective groups were not so strong. Even leading employees of one cultural institution have not yet been to the museum of the other. Both institutions are only about three kilometers apart, they are on the same street.

I had the impression that you know each other, there are some personal contacts, but otherwise you tend to keep to yourself. Ethnic and religious borders are drawn rather hard than soft. A really greater interest in institutional cooperation, it seemed to me, does not seem to exist (yet), never existed before or has been lost at some point.

Addendum:

If anyone has an idea how I can get further with my above question about understanding possible contacts even after emigration and across ethnic borders, I would be happy to hear any thoughts!

Ingwadiše go Lengwalo la Ditaba

Karabo

Dipego tša maeto Canada