tausend-fuessige-lamas

vakantio.de/tausend-fuessige-lamas

Let's dance!

Հրատարակվել է: 29.01.2019

Բաժանորդագրվել տեղեկագրին

When I dance, I don't dance on the floor, but the floor and I dance together.

During my studies, I had the opportunity to deepen my experience in the field of dancing, and it captivated me like nothing else. I took all the courses offered in this direction and rediscovered and learned about my body, perception, and expressive abilities. In my last semester, my classmates and I were able to plan and carry out a one-week dance project in collaboration with a school in Marburg. This gave us the opportunity to pass on some of what we had experienced firsthand. Our motivations and ambitions were high, but our experience in teaching was limited. For me, those days were very intense and exhausting. We, the five group leaders, often modified our weekly schedule late into the evening, tried to solve individual problems of the children, constantly searched for suitable ideas and exercises for our learning group, reorganized the room layout, and more. I think we were all under a lot of pressure during that time. But before all that, another feeling had imprinted itself in my memory. With a variety of exercises in perception, trust, and creativity, the children were able to develop exciting group choreographies in which they discovered, played with, and danced on and around the table. They used it as a wall and as a car, formed stars and circles out of it, rolled over it, and drummed on it. The final performance was a colorful and completely unexpected spectacle for many spectators. I suspect that during this dance project, not only some of the kids crossed and redefined habits and boundaries. We can rediscover our world when we dance.

My mind is racing as I prepare a rough plan for the week and the start of the first of two dance workshops. I read articles from my university days on my tablet, dig into my memories of seminars and workshops I've attended, visit the location and let myself be inspired. I'm incredibly excited. It will be the first dance workshop that I plan and carry out independently. And it will take place on South American soil in Bolivia, where probably no German sports student with loose hips can keep up with the hip swing of the Latinos. And above all: the workshop is only possible in Spanish. A language I have only recently started to learn. What luck that Sinja will be by my side. Sinja knows me well enough to simply translate what I try to express with hands and feet into Spanish.

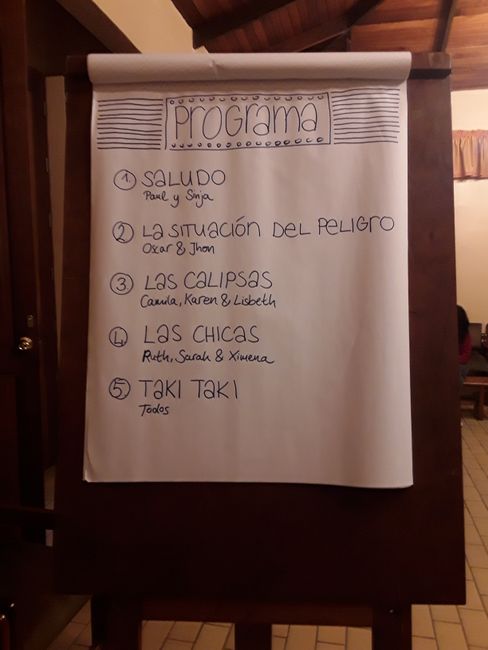

Before the first workshop in Tiquipaya started, we received a list. There were 11 names on it, boys and girls, roughly evenly distributed, aged between 12 and 16. We were happy that there were also so many boys. Then we heard that the participants did not voluntarily sign up for the course as planned, but that their mothers did it for them. The original idea was to offer the children a leisure activity during the current 2-month summer vacation that they would enjoy participating in. But that didn't work out. When we entered the "Salon" where the workshop took place, we had a small music box and our tablet with us, as well as a 2-liter water bottle, balloons, and the A4 sheet of paper, crumpled with my ideas and plans for the day due to excitement. We scheduled the start of the workshop for 9 a.m., after all, it was vacation time. But even at 9:20 a.m., only a fraction of the participants were present. Sinja reassured me, she knew how things worked and sent a few of the present ones to the houses to collect the absentees. This ritual would be repeated every day. So we sat in a scattered circle with enough distance, divided into boys and girls, with a slight delay (in Bolivia, they like to talk about the "Bolivian hour", which is the accepted norm for being late) and collected personal ideas about what "dancing" actually means. Besides theaters and television, dancing is mainly anchored in traditional festivities here. We discovered that in Bolivia, dancing takes place on many holidays throughout the year, on occasions such as birthdays, weddings, and even the carnival, where traditional clothing and expressive dance are celebrated. The dances that are typically associated with South America, such as Salsa, Bachata, or Rumba, are not so widespread here in Bolivia. After this basic research, we inflated our colorful balloons, some of them burst, and there was a lively atmosphere. To music, we played with the balloons using our hands, feet, heads, shoulders, and chests, throwing them through the air, holding them gently on our bodies with small movements, alone, with partners, or in coordination with the ceiling fans, standing, sitting, lying down, and getting up again. Some of the children enjoyed these exercises, while others found them difficult. Well, it did have a bit of a children's birthday party feel, to be honest. But it was important for us to get moving first, as detached as possible from familiar notions and with open senses. Afterwards, half of the kids became balloons themselves, adopting movements they observed and experienced with the balloons. It quickly became apparent that all of this was completely new for the kids. Sitting together in a circle, playing with attention, concentration, and mindfulness, having reflection sessions, and then even making a fool of oneself or becoming a balloon. It showed how difficult it can be to introduce a topic that completely breaks the expectations of the participants, as I had already observed in the dance project in Marburg. Both there and here, the kids expected us to line up and teach them a choreography. Instead, we did exercises like the "mirror," where two people sit opposite each other and one tries to mirror the movements of the other in slow motion, guided by soft music. We clapped rhythms with our whole bodies, performed acrobatic figures, let ourselves be led through the room with closed eyes, and watched the dance film "Pina" (Pina Bausch) until late in the evening (the film lasts a whole 2 hours!!), and danced improvised moves to the number 1 hit "Taki Taki" (here, in the classic style of standing in rows and as a fiery warm-up in the morning). The idea behind all this was to provide children with opportunities to immerse themselves in new perspectives of perception for themselves and others, to overcome boundaries of movement or adolescent inhibitions to some extent, and perhaps even broaden their ideas about dance and its possibilities.

I also became more relaxed with the language. Soon, I didn't even notice that everything was happening in Spanish. Often, thanks to my increased fluency, I could contribute to everyone's joy. For example, everyone burst into laughter when I said, "Ahora con pajera," trying to express "Now with a partner." This slip of the tongue had stuck with me, and so I often said "Pajera" instead of "Pareja," which is the correct term. Only after about a week and many laughs did Sinja and I learn that "Pajera" means "wanker." In addition to this little gem, Sinja and I also caused general excitement with a cheek kiss or even just a small hug, resulting in a loud chorus of "Tiieeneeeeees noviaaaaaa," which means "You have a girrrrrllllfriend."

We quickly grew fond of the group, despite their differences. There was John, who loves knowledge and reads encyclopedias, always slightly hunched, almost constantly in motion, and with a fine sense of his body. His spirit of discovery makes him fly through the world, and when he is happy, he tries to do a somersault. When he is touched in a benevolent and challenging way, his facial expression is irresistible, a mixture of crumpled and his mischievous smile, which he tries to hide. Then there's David, with a proud chest, radiating strength both physically and verbally. His charisma makes others follow him. He doesn't like to be led with closed eyes. But then he gathers his courage and allows it, but only with his fists raised forward protectively. With David, it feels like he's constantly in a power struggle or even a battle with others. Creative processes seem to be a threat to him, and he often interrupts them, quickly turning interesting movements into something ridiculous. Kamilla is a tall girl who often hides her laughter and avoids physical contact. At home with her family, she suddenly flourishes and seems to lose her shyness. However, showing interim results to the group was initially very difficult for her. She would chew on her fingernails, seem absent-minded, and be on the verge of tears. We were so happy when she not only dared to go on stage during the final performance but also became the beacon for her group. Karen's joyfulness, creativity, and "just do it" mentality repeatedly lifted the general mood. She climbed onto my shoulders with acrobatic elegance and with a good amount of courage, suddenly at dizzying heights. When Oscar grins after one of his numerous humorous remarks, his whole face lights up, and his positive energy carries you away. He's almost always one of the first to arrive in the room and confidently sits next to me on a chair with his cap. He gives me a challenging smile. He goes to the gym six times a week, but he doesn't present himself as a toned muscle but as a playful, curious, enthusiastic boy who can display an enviable uncomplicatedness.

This and many other lovable beings impress us during the workshop, sometimes in impressively open ways. The performances of our final show were inspired by the "Deseos 2019" (wishes for 2019). For the preparation, the kids collected wishes they had for the newly started year. Based on these wishes, they developed texts, stories, and some adorned the pages with pictures. With their permission, we were allowed a glimpse into these intimate revelations and were significantly reminded that we were working with children who have undoubtedly experienced terrible things. We were even more impressed by their will, accessibility, and love.

We secretly watched the kids practice in the garden that afternoon, and when we felt that not only we but also the kids were looking forward to the performance, a warm feeling of happiness filled us. When the big evening finally arrived, everyone made an effort to appear on stage: the girls put on makeup, styled their hair elaborately, and the boys coordinated their clothing and surprised us with masks. Unfortunately, two boys dropped out the day before the performance, and another boy didn't return after the fifth day. In addition to that, we had to exclude a new participant from the workshop because he repeatedly made hurtful and disrespectful remarks towards other participants, violating the rules established by the group. This was a particularly difficult moment for Sinja and me, and it led to many intense discussions and considerations. Of course, we would have liked to dance until the end. But one central rule was: everything is voluntary.

And what we felt was: the kids who were there wanted it. We rehearsed the run-through in a dress rehearsal, organized a spotlight, and assigned seats for 50 spectators. The "Salon" hardly looked the same anymore and resembled a theater space. Full of anticipation, we stood in front of the entrance, gathered around homemade cookies, and in a few minutes, the performance would begin... but at that moment, there were only a handful of spectators. I felt a sense of unease rising within me when Sinja called on everyone to gather the audience. So a few kids and I walked through the children's village, drumming rhythmically on a cooking pot and singing, calling people to come. It worked wonderfully, and a short time later (fortunately, not a full Bolivian hour later), the place was full: families, friends, and tias (aunts, as the mothers unfortunately went on vacation with the group that weekend). Sinja and I hosted the evening and proudly introduced each group. The first performance made a powerful and energetic start, the second took us on an exotic vacation journey with light feet, while the last one performed with a sense of closeness, calmness, and a touch of melancholy. As a finale, we all danced together in a revised group choreography to "Taki Taki." As a surprise, the mothers of the Tiquipaya children's village (from the first dance project) came on stage. I had rehearsed a choreography with them one evening during that week, and they really wanted to present it. When the mamasitas shook their shoulders rhythmically and circled their hips, no one could hold back. After the enthusiastic calls from the audience for an encore, the kids, Sinja, and I jumped on stage once again and danced an energetic final "Taki Taki." And amidst all the emotions, numerous people came to take photos with Sinja and me after the show. One more photo, now one alone and with Bolivian flags. The requests didn't stop, and my toothpaste smile was almost frozen when the last ones left satisfied. One minute after this dizzying flight to the stars, Sinja noticed that my pants were wide open. So, alongside our broad grins, all these photos proudly display a waistband wide open. Well, thankfully, something like that brings you back down to earth.

Sinja and I are still sitting in a bar on the evening after the last performance, talking about our experiences and what they mean to us. Sinja clearly states that working with large groups of children and teenagers is not for her. She said it's difficult for her to keep an eye on the group as a whole, assert herself, and she enjoys getting involved with individuals in a smaller setting. For me too, the group size, which is actually manageable for educational work, was a real challenge. After each day, we were both quite exhausted. But thanks to mutual support and increasing experience and security, I also noticed that I gained routine, clear goals, and confidence. I was impressed by all the different attitudes, movement styles, and words that the children used to express themselves. The field of bodywork/body therapy through dancing, for example, interests me a great deal, and I believe it offers wonderful opportunities to work deeply and with a lot of fun with children, teenagers, and adults. And I also realize that I'm still at the very beginning...

When Sinja packed her bags and left the children's village in Cochabamba five years ago, she had already deeply connected to this place and many people. After Sinja arrived again, this time with me in tow, recognized the familiar scent, and fell into the joyful embraces of the children, she showed me around the premises and we had dinner with the families, she said: This is like my second home. Today, I can understand it better. The children, the mamas, the place, the surroundings, the mountains, their destiny, they have a place in my heart too. We have formed a bond. Maybe we will dance together in some moments, even though we will soon be thousands of kilometers apart again.

Բաժանորդագրվել տեղեկագրին

Պատասխանել (1)

Yasmine

Ihr könnt sooo stolz auf euch sein! Freue mich schon, wenn Nini bei euch einen Tanzkurs belegen kann :)