Mit Geschichte(n) um die Welt

vakantio.de/mitgeschichteumdiewelt

The New Zealand Haka of the Māori in Italy. Or: Remembering in Monte Cassino

Հրատարակվել է: 20.05.2024

Բաժանորդագրվել տեղեկագրին

Actually, I don’t like large commemorative events or memorial sites.

This may be confusing, because it is my field of work.

But maybe that's exactly why.

What I don't like is the fixed, often routine; the standardized remembering; the commemoration that sometimes seems empty and hollow to me. Often a lot of things are totally familiar, expected and well-rehearsed. Commemorative ceremonies and anniversaries in particular are often a big circus - for politics; to be seen, to exploit what has happened and therefore also the dead for something completely different.

Most of it takes place in echo chambers: groups tell themselves what they want to hear, talk about and for themselves; remembering is often primarily related to oneself, to one's own community; if other groups are present, they often only act as extras.

There is a lot of talk: about solidarity, about being together, about freedom, about peace, about a better world and sometimes about the supposed meaning that the death of these dead had for today. Much of it is a great spectacle, sometimes a "theater of reconciliation", sometimes and often used to intensify nationalism. And then there is also great mourning, a search for meaning, collectively and individually, a search above all for support. Despite all the criticism and all the discomfort, for relatives, descendants and above all survivors and, at former battlefields, veterans, commemorative events are important. People travel from all over the world for such events. And so do I.

The idea of returning to Europe for the 80th anniversary of one of the most important battles of the Second World War, Monte Cassino, is… let's say special. Fair enough! - That's fine!

But since Monte Cassino is a huge thing both Down Under and in the Polish [diaspora] community and many people can relate to it, I thought: “Why not?” and couldn’t find any reasons against it, except that I wanted to stay in the Southern Hemisphere (which was/is no surprise).

Monte Cassino: 1944-2024. The 80th anniversary.

State ceremony in countries all over the world. And above all locally, in the small town with today 35,000 inhabitants; more or less halfway between Rome and Naples.

One of the largest and most important military battles of the Second World War took place in and around Cassino, especially in the spring of 1944. Some called the months of bloodshed, local fighting and, due to the many participants from all over the world, the Battle of the Nations of the 20th century.

In Poland and especially in the Polish diaspora, Monte Cassino is a heroic myth, perhaps the place of remembrance for Polish soldiers par excellence; the same applies to New Zealand, because a Māori battalion in particular fought here on the British side in 1944. The New Zealand narrative about Cassino ranges between a heroic story and stories about being cannon fodder for the British.

Many Māori volunteered for military service in the hope of being truly recognized as citizens of the British world. Their willingness to fight was appreciated when it was needed, but this was quickly forgotten when the war ended. In New Zealand, the surviving veterans were once again second-class citizens. The discrimination against Māori in New Zealand, which was seen as white and British, entered a new phase after 1945.

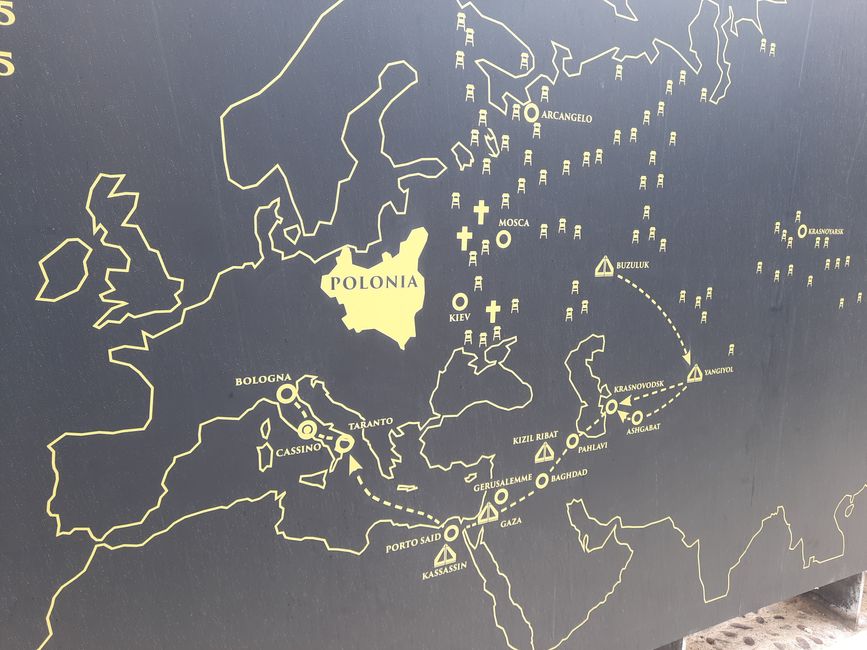

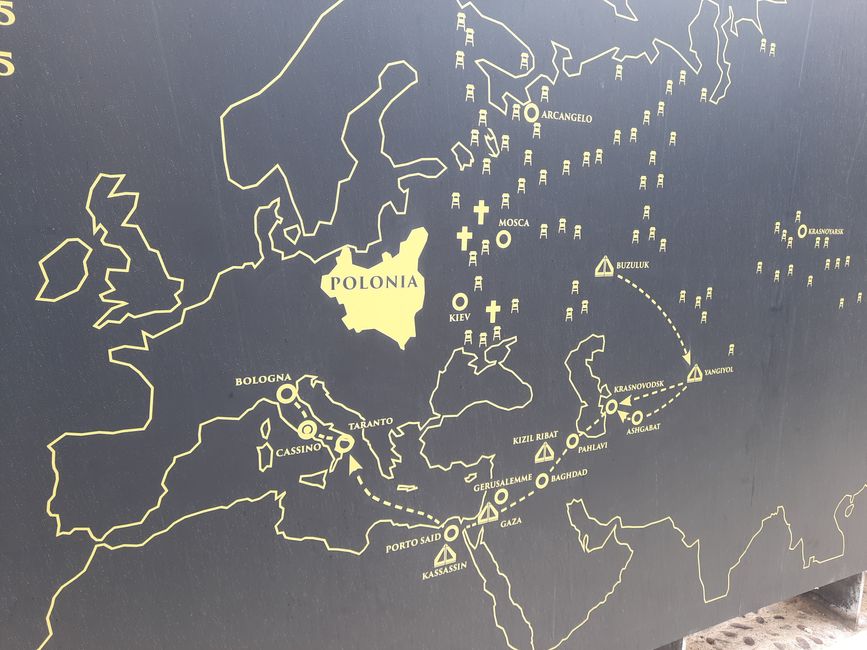

The Polish participants were organized in the so-called 2nd Polish Corps and had a very unique and above all complicated history: First, at the beginning of the Second World War, they were deported eastwards to the Soviet Union (Nazi Germany occupied Poland on September 1st, and the Soviet Union occupied Poland from the east on September 17th, 1939). Polish soldiers were thus taken prisoner of war by both Germans and Soviets from 1939 onwards. In the period that followed, the NKVD, the Soviet secret service, murdered over 22,000 Polish officers in Katyn and elsewhere - not to mention Nazi Germany here for reasons of space.

The Polish prisoners of war and Polish citizens who were then deported to Siberia were granted an amnesty after 1941 - Nazi Germany had attacked the Soviet Union and soldiers were needed. The well over 300,000 Polish citizens of all religions who were deported to the interior of the Soviet Union in 1939/40/41 now appeared to be a cheap mass of available troops. After a long back and forth, many were allowed to leave the Soviet Union via Central Asia and Persia and subsequently fought on the side of the Western Allies, especially the British. This Polish formation called itself the "Anders Army" (after their general Władysław Anders) and was then absorbed into the so-called 2nd Polish Corps.

Knowledge about this is mostly absent in the “non-Polish world” and thus also in the German majority society

and it gets even more complicated:

These (exiled) Poles fought in Italy, including in Monte Cassino, and later became the backbone of the Polish displaced persons in German-speaking countries and then, later, of the worldwide Polish diaspora. For them, the legitimate Polish government was the government in exile in London. They did not recognize the later communist government in Warsaw under Soviet influence. After the end of the war, these Polish soldiers of the 2nd Polish Corps were vilified by various sides, and especially by the communists, as collaborators, Nazis, anti-Semites and traitors. For some, this was true, for most, it was not.

What united the Second Polish Corps was the fight for a free and independent Poland. They fought against Nazi Germany AND the Russian-dominated Soviet Union.

Both the Poles and the Māori fought in the same battle over a mountain on which a monastery stood and (still stands today): Monte Cassino.

The place was more than symbolically charged: it was considered militarily invincible, but also a direct route to Rome, a deeply Christian place, because the Benedictine monastery was considered one of the oldest Christian and above all Catholic outposts in southern Italy, even the mother monastery of the Benedictines.

Not only did the Māori and Poles fight on the same front and on the same side, they also fought with men from India, with Canadians, Britons, South Africans, Americans, Moroccans and French. The world against German Nazi terror. That is how it seemed to those involved, that is how it was, and that is how it is remembered.

Commemorating all the victims of this bloodbath 80 years later is a challenge. For some countries it is a place of heroic struggle, for some a place of mourning, for some it is a place of pride. For most it is something in between. Some want and need religion, especially in this Christian-charged place; others are against it, because: which religion should, must, can dominate? There were also Orthodox, Protestants, Jews, but above all atheists, Hindus and Muslims among the soldiers.

May 18 and 25, 1944 are considered the most important days of the battle. On May 18, the 2nd Polish Corps captured the already completely destroyed monastery on the mountain - after other Allied units had tried unsuccessfully to do the same for weeks.

The Polish flag flew over the monastery ruins on May 18, 1944, and the Hejnał Mariacki, the trumpeting known from Krakow, rang out from the ruins of the monastery shortly before noon.

A week later, more mountains had been taken. The battle was considered over; the way to Rome was clear. The Allied soldiers were welcomed in the Vatican. There are hundreds of photos of the latter in the private collection of veterans.

How do we remember all of this 80 years later? Nationally and multinationally and in several cemeteries?

Difficult.

The various events I attend are something between mourning, major events, drama, carnival, nationalism, national chauvinism and (little) solidarity while at the same time appealing for cooperation and empathy.

For me, the most moving events were the two smallest of all the official events: those of the Māori from New Zealand.

It was "casual", as the Kiwis, the people of New Zealand, often are. Not aloof or too formal and stiff, but inviting and friendly, tough but also very warm. Even interrupting the protocol when emotions are too high to continue.

In my opinion, they were the only ones who managed to create real multicultural solidarity; whose commemoration seemed so genuine and authentic, whose commemoration was inviting. What was also striking was that in these speeches at the New Zealand commemoration, not only the civilian Italian victims found a place, but also the former enemies of the Māori, for whom they also prayed.

Now I don't know how this is connected, but a Māori woman spoke to me and asked if I was British. She had seen me several times in the last few days. I had to smile: "No, I'm from Germany." She replied: "I'm writing a book about my father, who was shot here at the train station. I would like to find out more about the German side. What is there in the archives about this?"

I have to pass, I'm not a military historian. "But I know someone who might know something." She gives me her card, she introduces me to someone, obviously someone with influence. I can't quite keep up, I just hear how enthusiastically they're talking about me. The Māori with grey hair and traditional tattoos is wearing a New Zealand straw hat; he looks at me, asks, no, more accurately states "Germany!" I nod.

He takes off his hat, grabs my hand, pulls me towards him and kisses my cheeks, left, right, hugs me warmly, for a long time. I am surprised, somehow touched, somehow irritated too. What is happening here? I wasn't expecting this.

"Have you ever been to New Zealand?" I'm asked. "I've just come from there," I say in a shaky voice. He takes my hand in his and looks me in the eyes. He doesn't say it, but I think that means "Good!"

This is followed by dances, songs, the Haka, the traditional Māori dance, in the middle of the Māori burial ground at the Commonwealth Cemetery. Dancing on the graves of the dead of the Māori Battalion who died here in 1944.

I am touched, I can't describe it any other way. They are beautiful, sad, stirring songs and then again impressive and intimidating (the Haka).

“Tomorrow at 6:30 a.m. at the train station. We're having a memorial service there. That was the most important place for our boys!” – “I'll come by,” I say. “For sure.” – “Sure!”

I put a few photos of Monte Cassino online and shortly before the commemoration at the train station, early in the morning European time, I receive a message from New Zealand. “ Kia ora Sarah - I have relatives who are buried in the Cassino War Cemetery at Monte Cassino. Thank you for attending the remembrance service.” A message from a firefighter and proud Māori from Titahi Bay, my home in New Zealand at the time. - “ Kia ora Sarah - I have relatives who are buried in the Cassino War Cemetery in Monte Cassino. Thank you for attending the remembrance service.”

Բաժանորդագրվել տեղեկագրին

Պատասխանել

Ճանապարհորդական հաշվետվություններ Իտալիա