Bolivia: La Paz

Objavljeno: 07.11.2018

Pretplatite se na Newsletter

Because Bolivia is one of the cheapest countries in South America, we had planned to take a 2-week language course in La Paz to deepen our Spanish skills. Unfortunately, the options were limited, and it wasn't easy to find a suitable school with available teachers at short notice. Eventually, we managed to book courses for 7 days at Instituto Exclusivo. We also found a hotel near the school that offered studios with 2 rooms, a microwave, and a fridge. Since we were staying for 10 nights, we were able to negotiate the price down. For the first time in a long time, we were staying longer in one place and even had something like our own apartment. We really enjoyed this change of pace. One night, the door latch of our bedroom fell out, trapping us inside. Despite multiple attempts to call the supposedly 24-hour reception, we couldn't reach anyone, and there was no window in the room. Our banging on the door and calling went unnoticed. We didn't even have water in the room, and of course, the toilet was outside. Eventually, Jörg decided to break down the door. Interestingly, the loud noise was heard more by other hotel guests who came to complain than by the hotel staff. So much for a 24-hour reception. The next day, we had a conversation with the hotel owner, who actually thought we would pay for half of a new door. Yeah right, as if that would happen!

The time at the school was very interesting and intense. My teacher Sonja drilled me on all the verb tenses I was missing in the 28 lessons. But there was also time to talk about Bolivian culture, and she told me an interesting story about how the president or the military apparently lost the government medal recently because they wanted to pass the time waiting for a delayed flight in the red-light district and left the medal in an insecure vehicle in a backpack in the parking lot. Some Peruvians apparently broke into the car and stole the backpack, but later returned the medal after the incident became public and all borders were closed. According to my teacher, it's typical for Bolivia that they used such a technical, high-sounding term to refer to the brothel, which most Bolivian people didn't understand. She even had to look up the term on the internet herself.

La Paz is a fascinating and lively metropolis, especially when seen from above, the huge city is absolutely impressive. To have the best view, we visited the somewhat hidden viewpoint Tupac Katari, which we eventually found thanks to the help of locals amidst residential buildings. But unfortunately, the contrast between rich and poor is also very clear here. The shoe shiners wandering around the city are particularly eye-catching. This profession is so stigmatized here that the men working in this industry even mask their faces to avoid being recognized. The wealthier people live in and around the city center, while the poorer people live in el Alto, a neighborhood on the cliffs far above the center, and take the long way into the city every day to try their luck as shoe shiners, street vendors, or something similar. For several years, La Paz has had a new means of transportation: the Teleférico (cable car). There are already 7 lines in operation, and there will be 10 in the end. Jörg and I had a lot of fun flying around La Paz with the cable cars, especially since it is definitely the most comprehensible and safest means of transportation for gringos. In the chaos of the city buses, nobody really understands. But apart from that, I really like the innovative idea of using cable cars as a means of public transport. It efficiently connects the poorer neighborhood of El Alto with the city center. However, the fare of 3 Bolivianos (about 0.45 Swiss Francs) per trip per line is a bit expensive for the local population, especially if you have to change lines multiple times. But my teacher told me that there are discounts available, which, among other things, benefit people who use the cable cars for their daily commute. Originally, there were only small city buses in La Paz that ran everywhere. They had formed cartels and thus had a huge power over the city. For example, if there was resistance to a planned fare increase, they would simply go on strike and paralyze the entire public transport system in the city. The vast majority of people here do not own a car and rely on buses to get to work, for example. The government didn't want to put up with this anymore and looked for its own solution. Since there are steep slopes everywhere in the city (thankfully, we don't need a gym anymore from constantly walking uphill and downhill), and since there is also a lot of water below the city, a subway was out of the question. So they opted for the Teleférico, which by the way comes from Austria and Switzerland, that must have been a huge order.

Right near our regular Teleférico stop, we discovered the Cafe 3-Besen with appropriate Harry Potter decor, where I just had to try the local (and really delicious) butterbeer.

We also got to know the bad or unpleasant side of La Paz. One Sunday, we headed towards El Alto to visit the Feria (Sunday market) there. The market itself is nothing special. There are hardly any items of tourist interest, mainly household items, car parts, and other junk. Nevertheless, it was quite interesting to get an insight into local customs. After all, it seemed like half the population of La Paz was flocking to this market, so the Teleférico was quite crowded. As we were strolling along, Jörg suddenly said that someone had spat on him. Of course, we had heard of the trick where someone spits on you or sprays mustard on you. And while someone kindly offers you a tissue to clean yourself, you are robbed. Although we didn't immediately think of this trick in the first moment, we actually just kept walking in reflex. However, the group following us in the crowd didn't give up and kept nudging us and pointing out the spittle on Jörg's shirt. It really happened in the heat of the moment that we stopped, and immediately we were surrounded by a group of seniors. Instinctively, I stood behind Jörg, with my waist bag and his bag between us, but I hadn't thought about his phone. It was only a brief moment when he took his hand out of his pocket to accept a tissue from an old lady, and whoosh, the phone was gone. He noticed it in the moment it happened, turned around, and said, "My phone!" At the same time, everyone in the group around us pointed in a different direction, so we looked around confused. And a moment later...they were all gone...vanished into thin air. Of course, with Jörg's phone. Although the whole thing was obviously very unpleasant, it's just not cool when something is taken from you, it was actually quite interesting in retrospect. How quickly the whole thing happened, you had no time to mentally grasp the whole situation, you just react in reflex. And that's exactly what the group exploited. It was also surprising how large the group must have been that was involved. And what shocked us the most was that they were actually all old people. The friendly grandfather next door, the frail old grandmother who carries their shopping bag into the bus. We had always expected to be robbed by young, mean-looking gangsters, but not by a group of old people! Well, we had one phone less now.

Since we now had to get a new phone, we went to the mobile phone mile the next day. It is very typical for Latin America that in larger cities there is a street for all kinds of products, where you can buy them in abundance. For example, there are streets where there are literally 30 optician's shops next to each other. How these shops can be profitable in the face of this competition is a mystery to me. In any case, when looking for glasses, you have the agony of choice among hundreds of glasses. Then there is a shoe mile, a lamp mile, a computer mile, a tool mile, a hairdresser mile, a wedding dress mile, etc. Anyway, we quickly found a new cheap phone that we could give to a robber if necessary.

We also overcame our bad feeling (as they say, after falling off a horse, you should quickly get back in the saddle) and went back to El Alto a few days later. This time to visit a Yatiri, who is a shaman. Although we both don't really believe in such things, we found it a funny idea to have our future read from coca leaves. So we visited the small houses where the Yatiris usually advertise their services. Initially, it wasn't easy to find a Yatiri who spoke Spanish, most of them only speak Quechua or Aymara. The Yatiri's future prediction was also not unexpected and quite vague: we would experience both good and bad experiences. Ah, a truly groundbreaking insight. Of course, it could be remedied by holding a mass for PachaMama (Mother Earth). Out of sheer curiosity, Jörg and I agreed to it and the Yatiri prepared everything for the ceremony. He stacked various things on a cloth, including coca leaves, wax, salt, alcohol, and glitter threads (from last Christmas?) as offerings to Mother Earth, and we had to blow on the pile. Meanwhile, he repeated ritual words and prayers, blessed the pile of stuff with the cross of Jesus Christ, folded the cloth together, touched our heads with it, and then burned everything together in the oven in front of the Yatiri's house. Then he sprayed the wall with a bottle of alcohol, apparently to read the alcohol patterns again from our future. Authoritatively and knowing, he nodded his head, pointed to the pattern of alcohol splatters on the wall, and said that it worked and now everything would get better for us in every way. Jörg and I didn't really understand how you could read anything like that from the alcohol patterns, but we acknowledged that from now on we would only have good luck, accumulate great wealth, have a happy relationship forever, and be in perfect health. We said goodbye to the Yatiri, who even gave us his business card. Probably for any future complaints. Afterwards, we took a ride on the dark blue line of the Teleférico, which allows you to fly across the entire (huge) El Alto neighborhood.

The famous shamanic market Mercado de Hechiceria in La Paz can be forgotten. It may have been interesting in the past, but now it has become a pure tourist trap. In addition to llama fetuses, herbs, alcohol, coca leaves, talismans, and other esoteric stuff, every shop also sells souvenirs on the side.

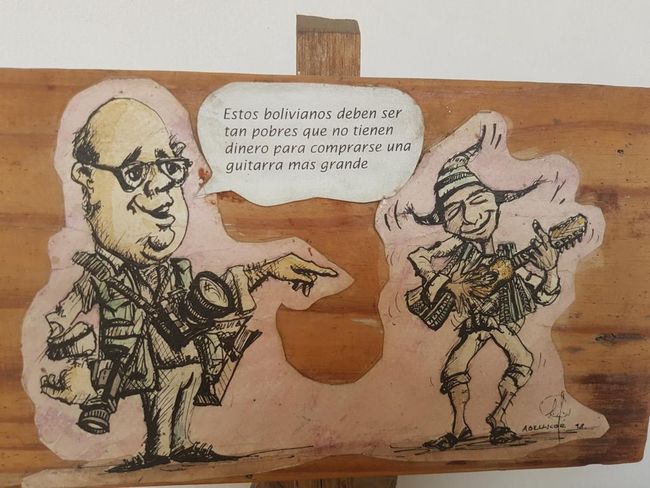

We also visited some museums in La Paz. One of the most interesting ones was the Museo de Instrumentos Musicales. It showcased not only numerous examples of native instruments but also instruments from around the world. Some quite unknown instruments were even available for us to play a little, which made the whole experience quite interactive and fun. The museum was founded by the charango master Ernesto Cavour (charango is a small guitar originally made from armadillos) and is considered one of Bolivia's most famous musicians. Every Saturday, he performs a concert in the Charango Hall of the museum together with Franz Valverde (Muyu-Muyu guitar) and Rolando Encinas (Quena flute), for which we also bought tickets. And I must say, I've been to many concerts in my life, but this was definitely one of the best I've ever seen, and all for only 3 francs entrance fee and in a small family setting. The 3 musicians each played a few solos on their respective instruments. Then they all played together, and it became clear that they are not only all truly masters of their instruments (Ernesto Cavour can actually play the small guitar on both sides!), but also that they have been close friends for many many years. It felt more like being part of a jam session than just passive spectators at a concert. So there were also comical inserts and the audience was actively involved, singing along, clapping, or dancing. It was a truly wonderful evening, and we had a great time.

The Museo del Oro exhibits some nice pieces made of gold, silver, and copper, but it is not particularly spectacular, especially if you have already visited the Museo del Oro in Bogota. The Museo del Litoral is about the War of the Pacific, which Bolivia fought against Chile and lost, resulting in the loss of territories, including the Atacama Desert and access to the sea. Although it is an interesting topic, the museum itself is not very remarkable. There is an almost incomprehensible film in Spanish and some old maps to see. The Casa de Murillo is more than boring, it is simply an old house where you can see old rooms with old furniture, old art, and old junk. The Museo Costumbrista is moderately interesting, especially the part about the Cholas.

In La Paz, there is also the tradition of Cholitas wrestling, a wrestling event where Cholas compete against each other. These "fights" usually take place on Sundays after the Feria in a multipurpose hall in El Alto. Although we're not really interested in wrestling, for the sake of broadening our horizons, we decided to attend these spectacles as well. However, since we no longer had any free Sundays, we attended a show on Thursday, where the fights have a more touristy character. And that was probably the most meaninglessly invested money during this entire trip. My conclusion is, on the one hand, that I find wrestling overall stupid. On the other hand, the shows were so poorly staged and predictable that the whole thing was truly ridiculous. The first two "fights" weren't even fought by Cholitas, but by guys. Only in the subsequent 3 fights did "pulling hair" and "swinging each other by the skirt and spinning in circles" come into play. Maybe the first fight was still somewhat funny, but the next ones were absolutely identical, I don't even know how to describe it, it was absolutely terrible. How can anyone find such a thing entertaining? At some point, I didn't even know where to look because of the sheer embarrassment, while Jörg was howling next to me. Oh dear, you can keep the entrance fee, but please give me back those 1.5 hours of my life!

The definitely most interesting museum in the city was the Coca Museum. Unlike the Coca Museum in Cusco, it was not particularly well set up, so there were hardly any noteworthy exhibits. But there was quite a lot of very interesting text to read, which was handed to us in brochure form. The coca plant is one of the oldest domesticated plants in the world. All pre-Columbian civilizations of the Andes had left evidence of the use of the coca leaf. The first information about the plant reached Europe as early as 1499. However, the Catholic Church soon denounced coca as "devilish," so it was banned in the colonies. Only when it was noticed that chewing coca leaves increased the performance of miners in the silver mine of Potosi, it was allowed again among the locals, and the consumption of coca was even ordered for mine workers. And thus, the locals also broke with their traditional rituals of using coca, and it became an everyday product. Like everything valuable, coca was also appropriated by the Spanish conquerors and taxed (to earn even more from the poor miners). The connection between mining and coca went so far that the price of coca leaves depended on the price of minerals. In 1860, the alkaloid in coca called "cocaine" was discovered, and from 1863, the (legal) cocaine boom began, first in the form of the popular coca wine Mariaru, later (1886) with Coca-Cola. Cocaine was also used as an anesthetic by ophthalmologists and dentists and became one of the most important medicines in modern pharmacology (even today, derivatives of cocaine play a major role in anesthesia). Only in 1914 was cocaine banned and in 1950, it was vilified, with the argument that coca reduced performance and was the reason for "mental retardation" and poverty in the Andes. Only plantations of industrial importance (e.g., for Coca-Cola, although the cola today no longer contains active substances from coca, only flavorings) are approved. Currently, 36 countries are allowed to legally produce cocaine. Interestingly, like in colonial times, the discovery of anesthetics, the spectacular success of Coca-Cola, and the millions of profits in the illegal drug trade alone contribute to prosperity abroad, while the recipient countries and their coca are blamed for the problem of drug addiction in the Western world. In the affected countries, the whole thing has partly turned into a veritable war, the Coca War. As part of the anti-drug strategy, in millions of dollars are flowing from abroad (especially the USA) to the affected countries because the local police forces are poorly equipped. (The USA represents 5% of the world's population and consumes 50% of the world's available cocaine.) In the field of cocaine production, there are also two other areas in which corporate groups operate legally, both located in the first world. Without them, the transnational nature of the drug trade would be hardly possible: 1. Banks that launder the money. 2. Chemical factories that produce and sell the substances for cocaine production. In most cases, the substances go directly from the countries of origin to the cocaine factories in the jungle. The "factory workers" who produce the cocaine are recruited from the large mass of unemployed and poor people in the cities. They belong to the group of cheap labor in the Third World, considering the risk, the health consequences, the working conditions, and the huge profit margins of the drug dealers. Their wages are about 5 USD per hour, which is good money in these countries. However, they usually receive their wage not in cash but in the form of coca paste. In addition to the fact that they are forced into criminality as drug dealers themselves, many of the workers succumb to the temptation of the paste and become addicted themselves. Ultimately, they work for their own addiction and end up in a vicious cycle from which there is hardly any escape. It is also interesting to compare social and religious rituals. In the Western world, alcohol is served at social events as a matter of course, during the Christian church service in the form of wine, together with the host. In Andean culture, coca replaces this role and connects to the divine and others. Coca leaves are consumed, exchanged, and offered to Mother Earth during rituals at social events. The exhibition also presents further facts about the coca plant and occasionally refutes the negative impact on performance, on the contrary. In addition to other positive aspects, it also helps tremendously against altitude sickness, which we had already experienced firsthand. It also addresses cocaine addiction, discusses addictive behavior, and shows how cocaine affects human behavior and the damage addiction can cause. What can one say about this? It is a truly complex matter. In the South American countries we have visited, coca is truly omnipresent. Bus drivers, vendors, and hiking guides have a "cocaball" in their cheek, every hotel serves coca tea for breakfast, and you can even buy tea bags of coca tea in every store. Although the Latin American work mentality often leaves something to be desired from a European perspective (e.g., when the lady at the ticket counter in the bus terminal is lying on the counter and reluctantly lifts her gaze from her cell phone to sell you a bus ticket in the most unfriendly and unmotivated manner possible, and in the meantime, you can count to 5 between each keystroke on the keyboard), I don't think that's because of coca. We ourselves chew coca leaves from time to time on hikes, and it actually has more of a performance-enhancing rather than performance-reducing effect. One might rather ask what the general pace of work would be like here without coca leaves. No, better not. Of course, I don't deny that the white powder cocaine is a devilish substance that can cause severe addiction and thus destroy people, lives, and families. But here in the growing countries, interestingly, there are relatively few cocaine addicts. It is predominantly the parts of the world population that are rather "well off" that are affected. And from the perspective of the people here, they simply cultivate a natural product that has a large market in many parts of the world. Who can blame the farmers for growing coca instead of potatoes when you know that potatoes can only be harvested once a year, while coca offers 4 harvests per year and is also very easy to care for? Who wouldn't do the same if their family at home was suffering from hunger? Although I genuinely feel sorry for all the people who fall victim to addiction, I still cannot blame these people here for cultivating a plant that has been part of their culture for thousands of years. And honestly, I will really miss my daily coca tea for breakfast, which has replaced the usual (mostly terrible) coffee months ago when we leave this region.

We also visited the cemetery of La Paz. The facility is huge and, although in the middle of the city, beautifully designed with lots of greenery. The cemetery is full of huge walls where the deceased are laid to rest. Each grave has a front with a glass window, which families decorate with small gravestones, flowers, offerings, mementos, or toys (in the case of children). Each wall contains hundreds of these glass windows and looks really beautiful and colorful. Wealthier families even have their own walls for their members. Otherwise, the difference between rich and poor is sometimes very clear. Some graves are very intricately designed and covered with tiles, while others are very simple and plain. Some even have a warning that the grave will be cleared if the due payments do not arrive by a certain date. We happened to be on the cemetery on a Sunday, and that was probably an unfortunate choice because there was a lot going on. The funeral ceremonies were held almost non-stop, while we were there for about 2 hours, 4 funeral processions, including the coffin and a Mariachi or other music group, passed by us. Hardly had one funeral procession passed by, the next one was already waiting in front of the chapel for "their deceased" to take their turn. Somehow a bit macabre. At the same time, many other people were also visiting the cemetery to visit graves of relatives, exchange flowers, or redecorate them.

What else did we do in La Paz? Right, there was the thing with the visa. Based on our previous experiences with visa extensions, we had scheduled two afternoons after school, just to be on the safe side. As it turned out, this wouldn't have been necessary, extending our residence permit was never as easy as here. Although it is true that Swiss citizens are allowed to stay in the country for up to 90 days, the Bolivian authorities only grant stamps in 30-day increments. So we went to the Oficina de Migracion in La Paz, lined up in the queue, told the officer that we wanted to stay 30 days longer, and zap! Stamp in the passport and done. No questions, no costs, nothing. He also pointed out that if we wanted the remaining 30 days, we could also pick up the stamp in Potosi, Sucre, or Santa Cruz. All the best and goodbye!

On our last evening in La Paz, we bought tickets for Peña Huari, where we treated ourselves to a delicious dinner and enjoyed a traditional music and dance show.

Although it was nice to stay in one place for 2 weeks again, and we actually liked La Paz a lot, it was time for us to move on. On to Cochabamba!

- City Park

Pretplatite se na Newsletter

Odgovor (1)

Manuela

Also das sich mega interessant i dere Stadt. Mir hends vorallem die Telefericos ato.......das muess doch es erläbnis si.🙂

Izvješća o putovanju Bolivija