Bukhara - why it's worth it

Publicatu: 27.09.2018

Abbonate à Newsletter

My first post about Bukhara was a bit ranty, I know, but I think it's important to point out what I consider to be a drastic development, as the demolition of historic houses in the old town continues merrily and the reconstruction madness (as our Dumont travel guide puts it) is celebrating its heyday. But one must not forget all the things that more than justify the trip here.

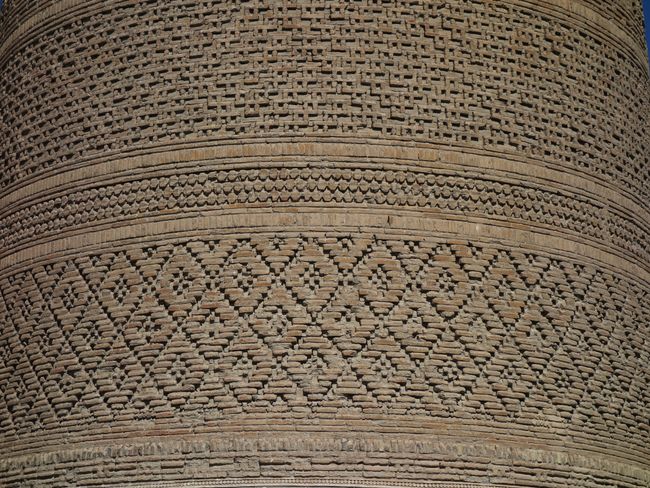

Of the famous sights, the Samanid Mausoleum, built around 900, is especially impressive. A building that has remained truly intact with perfect proportions and sensational decorations. The rightly famous Kalon Minaret is hardly inferior. Slightly younger and equally well-preserved, it was always a delight to pass by. And then there is a building that has not fallen into the clutches of the reconstructors despite its central location: the Magoki Attari Mosque has a magnificent portal from the time of the construction of the Kalon Minaret - and it is as decayed as one would like to see with such old stones. The Chor Minor is also worth seeing, a small gateway to a no longer existing madrasa, whose four turrets with their domes have remained intact, only the (sparing) tile decoration has been renewed.

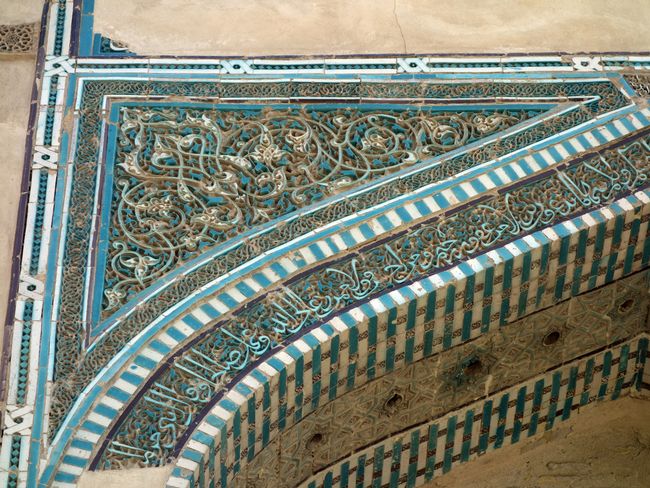

Everything else worth seeing falls once again into the category of minor sights and is located on the outskirts of the old town or in the new town of Bukhara. Hours-long walks in the dust of the old alleys or on the edge of the new (somewhat surreal) multi-lane boulevards brought us, above all, to the tomb of a Mongolian prince (murdered in 1358), which is decorated on the outside and inside with sensational tiles in a unique technique. The clay slabs were scratched in such a way that the finest patterns and characters remained as quite high reliefs - and these reliefs were then glazed in just a few shades of blue and turquoise, like tiles. The effect is stunning. By the way, there are also remnants of such tiles on the above-mentioned Magoki Attari Mosque.

An original mosque, at least for us, stands more or less on a street intersection in the midst of residential blocks. When it was built in 1119, it consisted only of a wall with a niche in front of which people prayed. Later, an annex was added to the wall, providing the faithful with at least a roof (consisting of three domes on pillars) over their heads. So the worshippers remained outdoors. This concept of an open mosque is very common here, by the way. In the long hot summers, galleries resting on carved wooden columns were always used. These galleries are attached to the outer wall of the room, which is available for prayers during the short but very cold winters. By no means all mosques have this winter variant, not even the particularly magnificent Kalon Mosque, a later addition to the beautiful minaret, originally from the early 16th century - as it stands now, probably from sometime in the last 20 years.

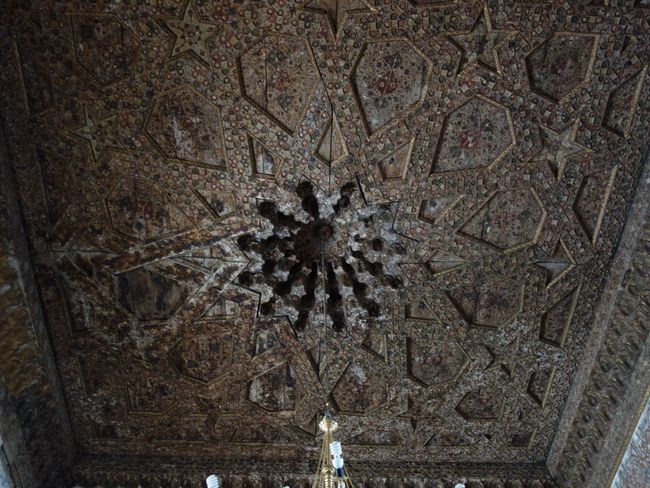

And finally, there is the original interior of the Baland Mosque from the 16th century. Here you can find very beautiful tiles in a quality similar to those found in the suburban mosques of Istanbul, although made in a different technique. They are not actually tiles (rectangular plates), but rather majolica mosaics, with each individual 'puzzle stone' having a shape, such as flowers, leaves, tendrils, and so on.

So there is indeed something to see in Bukhara, not so little and very good. It's just not the things you know from postcards.

Abbonate à Newsletter

Rispondi