Wir reisen, also sind wir

vakantio.de/wirreisenalsosindwir

Uruguay: Fray Bentos

Gipatik: 11.03.2019

Mag-subscribe sa Newsletter

We really wanted to go to Fray Bentos in Uruguay. Since we didn't have enough time to go directly from Colonia or Montevideo between Christmas and New Year, we took the more cumbersome journey from Buenos Aires. At least there were direct buses, which made the whole thing a bit easier. But it also meant crossing another border and getting more stamps in our already full passports. Well... curious readers might now wonder what the hell we were doing there, after all, it's not exactly a metropolis. In fact, it is mainly the slightly older generation who may be familiar with the name, namely those who have eaten products from the Fray Bentos brand or at least have seen them in the supermarket. In Fray Bentos, there is namely the historic meat processing factory El Anglo.

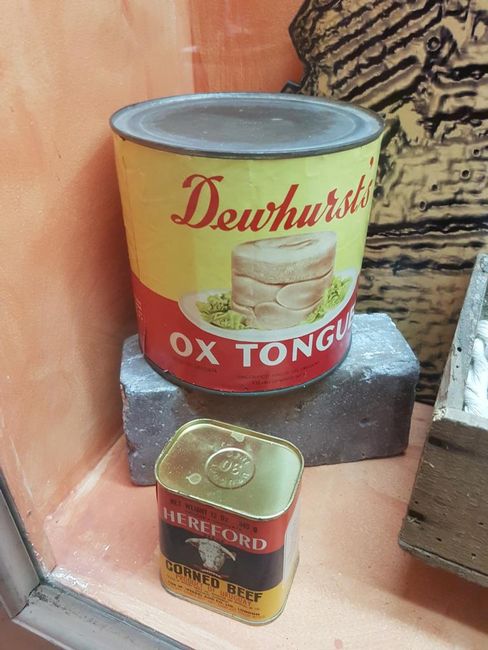

It all started in 1865 when a German named Justus Liebig founded the Liebig Extract of Meat Company in Fray Bentos. Liebig had already been dedicated to solving social food problems and had the idea to produce concentrated meat, so he invented the bouillon cubes. The factory quickly became the most important industrial complex in Uruguay. Why Uruguay? There was a lot of cheap meat available here. The first products were bouillon cubes and corned beef in cans.

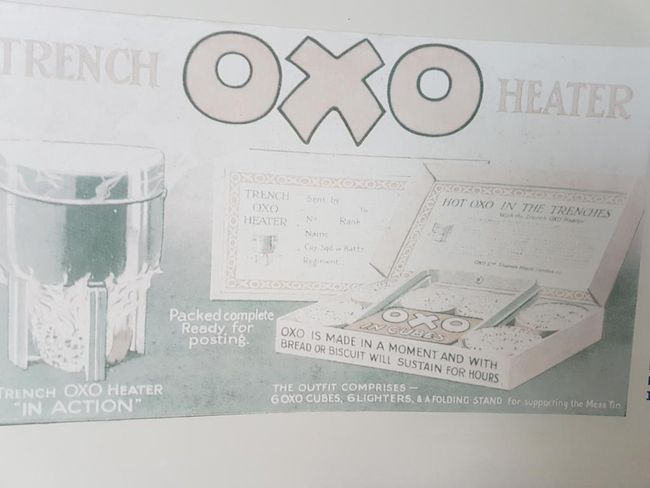

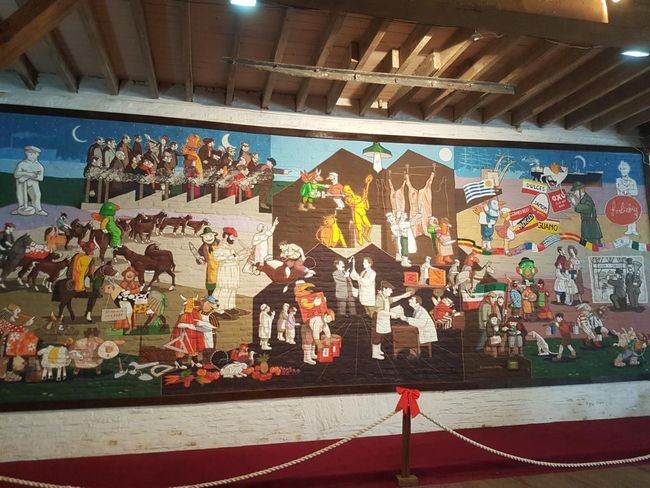

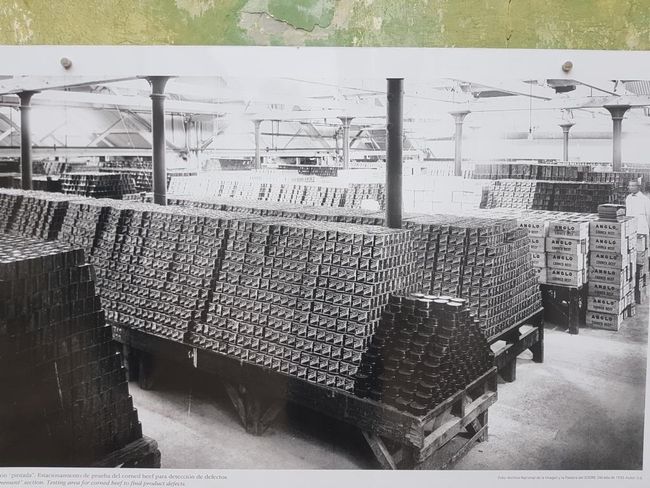

During the First World War, the Germans withdrew and in 1924 the company passed completely into English ownership and was renamed Anglo del Uruguay. The English built a huge cold storage facility, so that chilled products could also be added to the range. The company grew until the 1950s and was considered the "Cocina del Mundo" (kitchen of the world) during the Second World War. Soldiers on the fronts were supplied with products from Fray Bentos. Soldiers are said to have asked their families to send them food packages with OXO bouillon cubes. Complete boxes consisting of OXO cubes, cooking equipment and matches were available for purchase to be able to cook a hot soup in the field. But the products were also found in private households and in the lunch boxes of workers. In 1943, 16 million cans of corned beef were exported. Meanwhile, the product range comprised more than 200 other products, including fruits and vegetables in cans, jams, ham, ravioli and various meat products. In addition to cows, sheep and chickens were processed and everything from the slaughtered animals was used, wool, leather and feathers were sold, fat was used for the production of soaps and lubricants, fertilizer was made from bone meal and remaining scraps. It was said that the only thing from the cow that was not used was the "Moo".

In 1971, the English sold the land, infrastructure and buildings to the Uruguayan government, but not the brand. Products under this brand were subsequently produced in England, while the factory in Uruguay continued to operate under the name Frigorifico Fray Bentos. However, in 1979, the company was completely closed down because it was no longer profitable. In addition, the facilities were outdated and no longer met modern hygiene requirements.

The work in the factory was hard, but the working conditions were fine. Boys could start working in the factory at the age of 14 after completing primary school. Houses and quarters were provided for the workers around the factory. There was a school and a hospital, a music band was formed and a soccer club. Folk festivals were also held to entertain the workers. It is estimated that more than 25,000 people were employed there from the time the factory opened until its final closure. Immigrants from more than 60 countries came to Fray Bentos in search of work.

After visiting the museum, we made our way through the complex labyrinth of passageways, paddocks, and abandoned slaughterhouses. The paths through the area are paved with metal plates that were used as counterweights in ships. For this reason, the tour cannot be conducted during a thunderstorm, as the risk of lightning strike is too high.

During the guided tour of the facility, we first visited various control and engine rooms. The rooms with the old machines are extremely popular as a photo backdrop for 15-year-old girls' parties in their beautiful dresses, we were told.

Next, we visited the area where the meat was cooked down to concentrate. The idea that the cooking vessels were not made of stainless steel at that time and that these vessels were in operation until the closure in 1979 was not very appetizing.

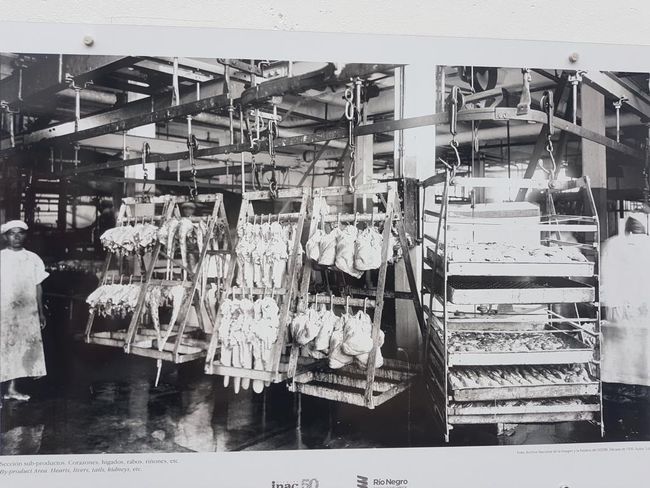

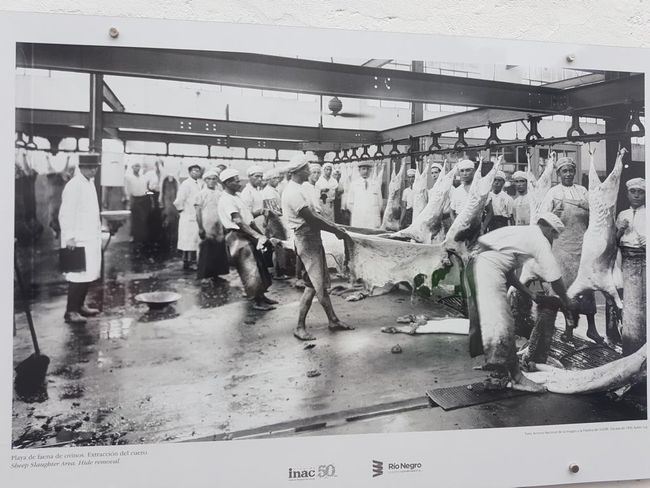

In the outdoor area, various photographs were displayed showing daily life and work in the factory.

The visit to the empty slaughterhouse was a bit eerie, to say the least. The animals were led on foot from the often remote farms to the slaughterhouse and lost weight again on the way. Therefore, they were held in specially prepared pens and fed again before slaughter. They were then led through special corridors to the slaughterhouse. The corridors narrowed more and more, so that in the end only 3 animals walked side by side. The animals were killed with a hammer and then dropped into the slaughterhouse through a flap. There they were hung up so that they could be efficiently transported through the various processes of bleeding, removing the head, and skinning.

The visit to the cold storage facility was also very impressive, mainly due to its dimensions, as there was not much to see inside and much of it is no longer intact. The cold storage facility is huge, measuring 100x40 m and is 5 stories high. 70 km of pipelines were installed to distribute the ammonia necessary for cooling. In the museum, a short film was shown in which former workers talked about their time at the factory. An old man said that his first job as a boy was to open and close the heavy doors of the cold rooms when something was being transported in or out. He said he opened and closed them about 800 times a day.

Finally, we visited the office area where the administrative matters of the company were handled. An accountant tended to shuffle his legs while sitting on the office chair during work. The grooves of this continuous shuffling movement can still be seen in the wooden floor. We also looked at the office of the director, who had a direct view of the main gate through his window and could see who or what entered and left the premises. The presence of employees and their stay in various areas on the premises was closely monitored by means of metal plaques. When they moved between different areas, they had to show their plaques and their personal identification number, which was engraved on them, was entered in and out of books.

The visit to the Anglo factory and the associated Industrial Revolution Museum was really very interesting and certainly a very worth seeing place in Uruguay. However, only a few (foreign) tourists come here. In fact, everyone in Uruguay looked at us with big, astonished eyes when we told them we had been to Fray Bentos. It is definitely worth coming here to visit the UNESCO World Heritage site.

In the town of Fray Bentos, there is not much else to see, perhaps a walk along the promenade is worthwhile in good weather. Otherwise, you can quickly see everything here, which is why we quickly drove on after visiting El Anglo.

Mag-subscribe sa Newsletter

Tubag (1)

Manuela

Vielen Dank für die neuen Beiträge, die schönen Fotos und interessanten Einblicke in fremde Kulturen.

Übrigens habe ich mich „gefreut“ das gestreifte T-Shirt mal wieder zu sehen 🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣lieber Gruss an den Träger

Mga taho sa pagbiyahe Uruguay