maxikainafrika

vakantio.de/maxikainafrika

//Kharas-Region

Wɔatintim: 26.12.2021

Kyerɛw wo din wɔ Newsletter no mu

Wild Horses of Garub

On the way from Lüderitz back inland, an inconspicuous brown sign on the tar road in the middle of nowhere points to a "Wild Horses View Point". This seems even more surprising when driving, as there is no civilization, roads, houses, trees, or bushes to be seen, only vast, endless desert steppes. However, if you follow the inconspicuous turn-off (which we had overlooked on the drive to Lüderitz a few days before), you will reach a hut with a corrugated iron roof about 500 meters further, in front of which one or two cars are parked. We park next to it and enter the hut, which is actually just a few covered benches without side walls. At first glance, nothing seems to be happening here, here in the middle of nowhere. But just a little bit below the covered shelter, at a trough about two meters long, we see them: wild horses. They frolic around the water hole and quench their thirst alongside an oryx and an ostrich. A few foals scurry around between the long, brown legs of the horses, occasionally they rear up on their hind legs and seem to frolic with each other. The fact that two people sit mucksmäuschenstill a little further away, observing them curiously, does not seem to bother the herd at all. In the nearby Klein-Aus Vista Desert Horse Lodge, where we stay overnight at the campsite, visitors are informed about the wild horses. The wild horses of Garub, the location of the water hole, are descended from the domestic horses that the German protection force transported from Europe to German South West Africa during colonial times. Strictly speaking, they are not wild horses, but rather feral domestic horses that have presumably been roaming the desert in search of water and food since the First World War. Nevertheless, the horses have adapted to the harsh desert conditions in a very short time. Currently, there are still about 80 to 90 of the deep-brown animals threatened with extinction. Here in Garub, they find water far away from civilization in order to survive in the desert.

BrukkarosA bit further inland lies the 1590-meter-high Brukkaros, which at first glance looks like a volcanic crater but is probably more likely an inselberg formed by erosion. There used to be a campsite at the top of the mountain, near the approximately 350-meter-deep crater rim. Since the place is no longer managed, campers come here for wild camping. Already on the way there on the sandy gravel roads, it becomes clear that we are off the beaten tourist path. In the nearest town, Berseba, about 20 kilometers from Brukkaros, we do not see the typical signs pointing to guest houses or other tourist accommodations. Except for a rundown supermarket, there are only corrugated iron huts, a church, and a few slightly better houses along the only major road through the village, as well as many people in the streets. Just past Berseba, the old gravel road first takes us to Brukkaros and then a short but extremely demanding off-road track up to the mountain to the edge of the crater. Despite our 4x4, we can't make it all the way to the top, where remains of the campsite can still be seen on the crater rim. We stop halfway on a reasonably flat area and camp wild there. The view is even better than at the crater, because here we have a view of the mountain in one direction and a panoramic view of the wide, green landscape, under which red sandy soil shimmers. Far away from civilization in the middle of the wilderness, you feel like the only people in the world, even though in the distance you can still see a few lights from Berseba. But the stars in the sky shine brighter and more beautiful.

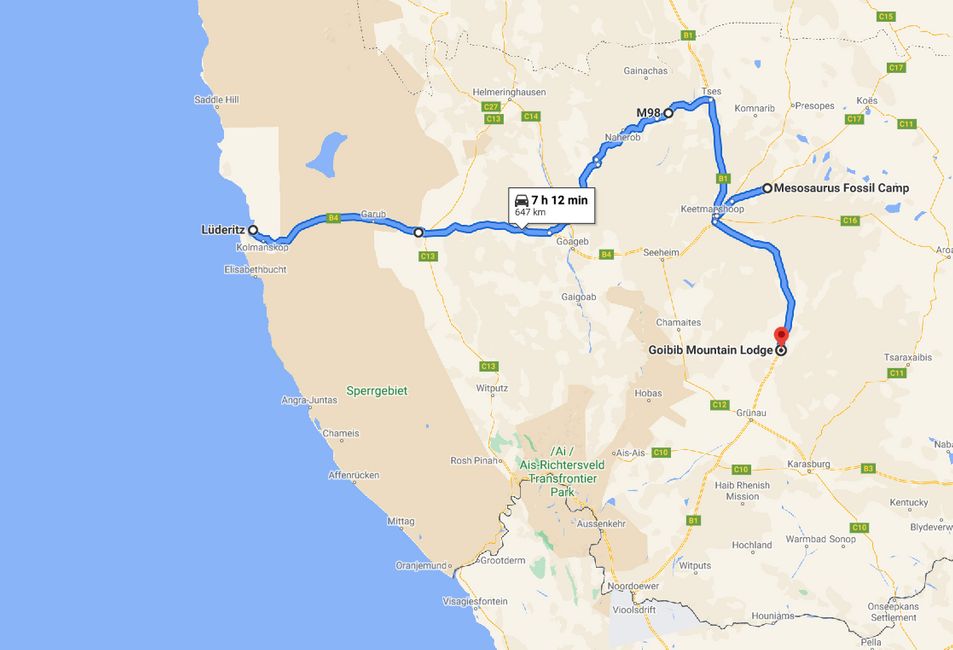

Quiver Tree ForestOn the drive to Keetmanshop, the capital of the //Kharas region, the sky clouds over. For the first time in four weeks, the first raindrops fall. Not ideal for camping, but a true blessing for the people, farms, and nature here. How often have we been told that in some areas, it hasn't rained for several years. Unimaginable for us Germans, but bitter reality here. The droughts and extreme weather events caused by the climate crisis are also noticeably increasing here. Near Keetmanshop, we see the typical quiver trees (English: Quiver Trees, Afrikaans: Kokerboom) for the first time in the //Kharas region. //Kharas (the special characters represent a click sound) is translated into the Nama language of the Nama people as quiver tree. The quiver trees (Aloe dichotoma) that grow here in southern Namibia and northwest South Africa have already been declared national monuments in some places. They are particularly beautiful to look at when the sun sets behind them on the horizon and the beams of light penetrate through the individual branches. The tree is named after the quivers made from the trunks by the San people. Our visit is worthwhile not only because of the quiver trees. Our campsite, the Mesosaurus Fossil Camp, which consists of a few secluded spots in a dry riverbed far from civilization, is also home to the Mesosaurus, whose fossils were found here. So we not only learn about the local flora and fauna but also expand our geographical-biological knowledge of the animal that lived here 270 million years ago. In the fossils that the farm owner shows us during a tour of the property, we can even see the individual ribs as well as the hands and finger joints.

We make our last stop before the Fish River Canyon at the Goibib Farm. Originally a cattle farm, the owner also accommodates guests in some rooms and campsites. Due to the travel warnings issued by European countries, African tourism is once again coming to a standstill. All the guests here have canceled, and we are - once again - the only campers for miles around. Good for us because as a result, we are allowed to use the guesthouse pool and enjoy a farm tour where we get to see antelopes, giant birds, and ostriches, in addition to the approximately 350 cattle. Compared to these huge grazing areas inhabited by the cattle, each European biodynamic farm is a joke. Only about ten to fifteen of the cattle here are slaughtered and sold each year, and only if they do not fit into their herds and cause problems. If we have to have livestock farming, then it's better this way. Since the bushes and grasses provide enough food for the cattle and there is more than enough grazing land available, this form of livestock farming (apart from methane, etc.) is still relatively environmentally friendly. Working with nature and not against it is also the decisive keyword here, as so often.On St. Nicholas Day, the Christmas fever overwhelms us, so we want to bake some cookies with our limited resources. The ingredients are actually not a big problem, because with flour and baking powder, we can also conjure up some pancakes for breakfast. Just add some margarine, chopped chocolate, mashed banana, maple syrup, and cinnamon, and we have mixed ourselves a delicious cookie dough. Problem: our camping equipment is good, but unfortunately, it does not include an oven. If you believe the internet, it is also possible to bake cookies in a pan, but that doesn't work out so well for us. The gas burner almost burns the pieces of dough from the outside while they are still very soft on the inside. Never mind because our first cookies actually taste pretty good! Now Christmas can come, we are ready. Munch.Kyerɛw wo din wɔ Newsletter no mu

Anoyie

Akwantuo ho amanneɛbɔ Namibia na ɛwɔ hɔ