You-Me and Marco Polo

vakantio.de/you-me-and-marco-polo

Iran

Ku kandziyisiwile: 29.05.2019

Tsarisa eka Xiphephana xa Mahungu

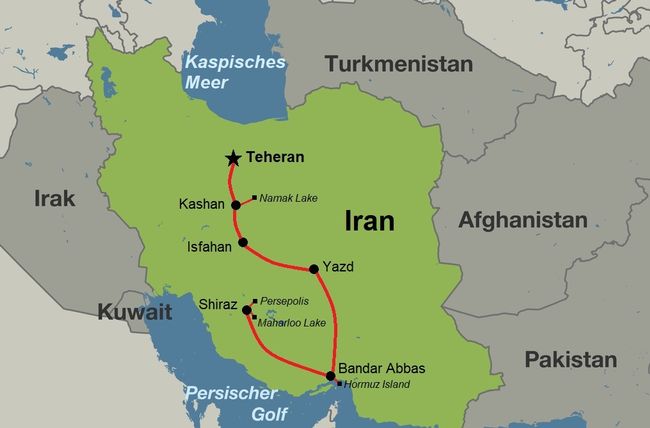

Almost all tourists who travel to Iran have something in common: they have mothers who worry and try to dissuade their child from traveling to Iran - whether the mother is from Italy (Marco), from Cuba (Yumi) or, as in the case of our hotel receptionist in Dubai, from Kenya. Most mothers don't know much about Iran, but they know for sure that it is dangerous there. The bad image of Iran is not surprising. After all, in our media landscape, we only hear, read and see bad things about the country. It starts with the neighboring countries: Iran is nestled between Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. In addition, the Iranian government is militarily active in numerous hotspots such as Syria and Yemen. And then there is the Iranian nuclear program, the harsh US sanctions, and the fact that Iran denies the existence of Israel.

Our biggest concern before arriving in the only Shiite theocracy in the world is paradoxically also the greatest hope of our mothers. Because it is anything but certain that we will even be able to enter Iran. According to Iranian immigration regulations, no one who has been to Israel is allowed to enter the country. Therefore, all passports are scrutinized for Hebrew characters during the visa application and upon entry. Although we do not have an Israeli stamp in our passport despite our visit to Israel half a year ago (the Israelis don't want to "brand" tourists and instead give out separate entry tickets), unfortunately, we traveled from Israel to Jordan by land and therefore have a Jordanian stamp in our passport - and an unmistakable stamp from the Israeli-Jordanian border crossing. Therefore, in anticipation, we are not getting our Iran visa at Tehran airport, but at the Iranian embassy in Buenos Aires. Although it takes five weeks from the first application to the issuance, we ultimately receive the visa personally from the Iranian consul, along with a pack of saffron, a handshake, and a warm "Welcome to our country!"

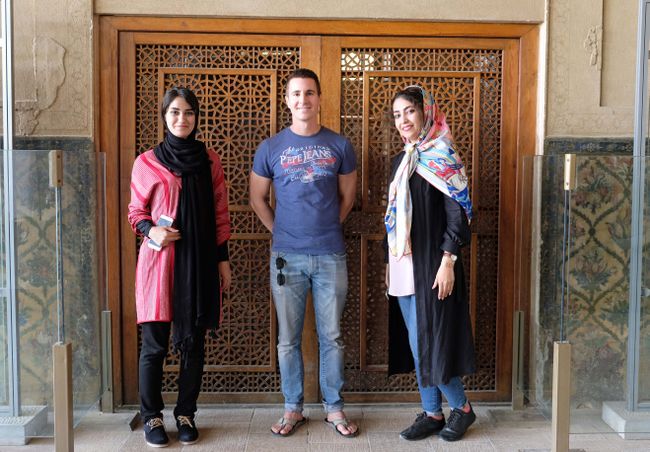

A few days later, we are in the plane from Istanbul to Tehran and are looking forward to more samples of Iranian hospitality. The first impression on the plane is positive and cosmopolitan: the Iranians, especially the Iranian women, in our plane look "normal", i.e., 90% are not veiled, only a few women wear a black cloak with a headscarf. However, we do not see a full veil in the form of a burqa or niqab (the eye slit thing) anywhere. But shortly afterward, we are met by anything but cosmopolitanism at Tehran Airport. The problem is surprisingly not passport or visa controls, but the Iranian dress code. In Iran, all women or girls over the age of 9, regardless of their origin and religion, must veil themselves in public. Legally speaking, this begins the moment our plane touches Iranian soil. And indeed, swish, all Iranian women who were dressed like Yumi before suddenly have a headscarf and long-sleeved clothes. Yumi, too, now unpacks her "headscarf" or her converted scarf and her black jacket and instantly transforms into a pious Muslim woman. Any woman who does not comply with the dress code in Iran and is caught by the Iranian morality police risks imprisonment. Yumi decides not to protest for now, which is why we have no problems passing through immigration.

We spend the first few days in the capital Tehran, which has about 20 million inhabitants. We are surprised at how clean and modern everything is here. The streets are in very good condition, there is no garbage lying around, and everywhere there are new, bright shops with large shop windows. There is also a subway here, a top modern one with sparkling clean stops. Many young women are also polished to a high gloss or made up with a lot of makeup - probably to compensate for not being allowed to dress sexy. In addition to artificial eyelashes and bright red lips, we notice one more thing: quite a few women walk around with a large bandage on their nose. We quickly learn that this has nothing to do with domestic violence or a religious ritual, but rather that many residents have their characteristic hooked noses operated on and straightened to look more European and therefore more beautiful. We hear and are amazed: There are more nose operations in Iran than anywhere else in the world! The women are so proud of their nose correction that they voluntarily wear a nose plaster for months after the operation. They want to signal that they come from a good family and can afford such surgery. Some women - we hear - even stick a plaster on their nose as a status symbol, even if they haven't had surgery.

In addition to the veiling requirement, there are numerous other behavioral rules in Iran that we must adhere to from the first day. For example, unmarried couples should refrain from holding hands and men are not allowed to shake hands with women as a greeting - unless the woman offers it herself. The international OK sign (thumbs up) should be avoided if possible because it originally means "stick your finger in your butt!" here. Similarly, one should refrain from blowing one's nose in public because it is about as bad as vomiting in one's handbag.

When we first arrived at the hostel, we wanted to buy a few bottles of water as usual and were informed that tap water in Tehran can be drunk without any problems. "Wow, I wouldn't have thought that!" Marco says euphorically. The tap water tastes pretty good too, as it comes from the surrounding mountains where the locals like to go skiing in winter. The parallels with Switzerland go even further: the level of education is high, many people in our age group speak English, are curious, and technologically up-to-date. If you want to travel cheaply from A to B, you can order a "Snapp" - the Iranian version of Uber - via smartphone. We also notice that Iranians are very decent and restrained in their dealings with each other. The big market or bazaar in Tehran is almost eerily quiet, and there is no honking as in other big cities on the notoriously crowded streets. On our first evening, we meet with the Iranian couple Alireza (he) and Masha (she) for dinner, where we learn more about both the progressive and the backward Iran. This starts with the measurement of time. Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the normal calendar no longer applies here; instead, the Islamic calendar is used. So we are not traveling in the year 2019, but in the year 1398. The more we learn about the background of the revolution, the more it feels like we have landed in the Middle Ages.

The question of where exactly we have landed is quite justified: Iran has only been called Iran since 1935; before that, the country was called Persia and was the largest empire in the world about 2500 years ago. The Persians or Iranians are not Arabs, but they were conquered by them at one time, which is why Islam has been the state religion for a long time and almost all Persians/Iranians are Muslims. About 100 years ago, there was a democratic revolution led and won by Western-oriented Iranians. Persia then received a modern constitution, including the separation of powers and a parliament, and was ruled by pro-Western "Shahs" (kings) for two generations. They modernized the country and restricted the power of the Islamic clergy. For example, a ban on veiling was introduced in 1936, and in 1963 (before Switzerland), women's suffrage was introduced. However, the Shahs also had their negative sides, for example, they were very corrupt and authoritarian. Protests against them were consistently crushed, and dissenters were imprisoned, which ultimately led to a second revolution - the one in 1979. The last Shah of Persia had to leave the country in a hurry. Although the revolution was led by students, communists, and moderate religious people, surprisingly, a religious hardliner seized power after that.

This man was named Ayatollah Khomeini and with his Islamic Revolution, he turned the country into what Iran is today: a strictly religious theocratic state, in which the Quran is the law. Khomeini declared himself the "Supreme Leader" or dictator who has the final word on everything. As his first act in office, he reversed all the reforms of his predecessors and passed a series of new laws based on the Sharia (Islamic legal texts). For example, it is stated there that girls from the age of 9 and boys from the age of 13 are allowed to marry if the parents agree. Or that husbands have the right to the sexual availability of their wives and can enforce it with violence. Women are also only allowed to work with the consent of their husbands, visit their own parents, have a passport, or get divorced. Beatings or sexual violence by the husband are expressly not grounds for divorce, on the other hand, the husband can divorce his wife at any time without giving any reason and usually get custody of the children. Adultery is indeed forbidden for both women and men and is punishable by death, but men are allowed to have up to 4 wives at the same time and can legally enter into a temporary marriage for 30 minutes to 99 years if they want to have an affair. "Wow, I wouldn't have thought that!" Yumi states astounded. Fortunately, the reality in Iran is not so extreme, as many laws from the Sharia are not accepted or are ignored by Iranian society. In Tehran, for example, we occasionally see young women who do not wear a headscarf. And since recently, one of these women was caught by the morality police and sentenced to a month in prison, a veritable anti-headscarf protest wave has been sweeping through the country: every Wednesday, hundreds of women, especially in Tehran, take selfies in public without wearing a headscarf and post them on Instagram as a sign of solidarity.

The rights and obligations in marriage are also different in reality. "There are only a few men who have more than one wife," Alireza says, "and they are all Arabs, not Persians!". To make sure, his wife Masha, who is not religious, simply had her husband sign a marriage contract like many other Iranian women, which grants her all those rights that the Sharia would deny her. "Speaking of not being religious," we ask interestedly, "how many Iranians don't care about religion?" Alireza and Masha give us a number that initially astonishes us but is later confirmed by our acquaintances: at least 60% of the population is not religious - but they pretend to be in public. The reason is simple: in Iran, Muslims face the death penalty for turning away from the faith. It is, therefore, not surprising that according to official statistics, 99% of the population are Muslim :-) There is officially no place for gays and lesbians or atheists in Iran, as homosexuality is also forbidden, and homosexual acts are punished by death. Unfortunately, the harsh criminal law is not just an empty threat but is regularly put into practice. Given the size of the population (a whopping 80 million, the same as in Germany), there are more executions in Iran than anywhere else in the world. Paradoxically, the country also holds another world record, namely the most gender reassignment surgeries per capita. Just because the state only accepts heterosexual couples, all Iranians who feel they are in the wrong gender or attracted to the same gender receive financial support from the government to undergo gender confirming surgery. The main thing is to comply with the rules of the Sharia. This also applies to heterosexual couples. For example, in the Persian language, there is only the term "husband/wife" to describe a relationship between a man and a woman. There is no translation for the word "boyfriend/girlfriend" in the sense of boyfriend & girlfriend because according to Islamic jurisprudence, this word is not necessary. Extramarital relationships between a man and a woman are forbidden, which is why couples cannot live together without getting married.

Yumi gets angry for the first time: "Instead of regulating who can wear what, the government should take care of the begging and working children!" Where she is right, she is right: we see street children here every day. According to Lonely Planet, there are over 2 million street children in Iran, and most of them work and beg on behalf of criminal gangs. They have to hand over everything to them at the end of the day and in return, they receive something to eat and a roof over their heads. Often, orphaned children end up with these gangs, or children from impoverished families are sold to them. The government is overwhelmed by the situation and does nothing about it (with the incorrect explanation that these are migrant children and not Iranian citizens). On the other hand, stray dogs in Tehran are systematically shot dead by city employees because they are considered unclean in Islam. So we practically don't see any dogs, but there are many street children and even more stray cats that are pampered and fed by passers-by accordingly.

The longer we travel south, the more we feel the presence of the 40 (or fewer) percent in Iran who are religious. The full veil rate and the volume of the minaret loudspeakers increase in these latitudes - and unfortunately also the temperatures. Yumi, who is not particularly heat resistant anyway, copes bravely with her headscarf and long clothes, and together with Marco, she visits the sights in the country. In order not to offend anyone and not to violate any laws, Yumi pays close attention to her headscarf always being well in place. The only positive thing about veiling is that Yumi is sometimes mistaken for an Iranian and addressed in Persian. We then ask ourselves for the first time why Muslim women actually veil themselves and why each one does it a little differently. The answer: The Quran says that women must veil themselves; however, "what" or "how much" they should veil is not specified and is, therefore, a matter of interpretation. Therefore, in Afghanistan, there is the burqa with a grid window, in Saudi Arabia, the niqab with an eye slit, and in Iran, the nun-like chador as well as the simple headscarf. By the way, the Quran states at one point why women must veil themselves, namely so that they are not harassed by men. It is ironic that today in Iran, it is mainly the conservative grandmothers who walk around in chadors, while the young women do everything they can to show as much skin, hair, and contours as possible :-)

When we arrive in Yazd, it is quite windy as we walk through the old town, and Yumi wants to take some photos of a mosque. Then the unthinkable happens: Yumi's headscarf is blown away by the wind, exposing her beautiful hair. But since she is busy taking pictures, she doesn't notice and doesn't correct her attire right away. Suddenly, a man comes up to Marco, waves his hands over his head, and shouts, "Hijab! Hijab!" - meaning "Tell your wife to put on her headscarf again!" Yumi gets angry for the second time: "This is so annoying! This country simply does not deserve to be visited by tourists!" Yumi suddenly becomes a militant feminist who sees only Islamic oppressors and oppressed women everywhere. She is upset, for example, that in restaurants, Marco always gets a menu card, while she is completely ignored by the waiters. The locals explain to us that (once again) not everything is as it seems: in Iran, it is simply impolite for a man to interact directly with a married woman. So Yumi is not being treated disrespectfully like air but, on the contrary, being intentionally ignored as a sign of respect! However, the damage has already been done, and Marco cannot repair it, not even a little later when he points out a positive street scene that should cheer her up: "Look, there's a woman driving a car, and the man is sitting in the passenger seat." Yumi doesn't react much, which is why Marco adds, "That's progressive, isn't it?" Now Yumi smiles and explains her reaction: "Oh, I thought for a moment that the men here are simply spoiled and prefer to be driven around by their wives rather than drive themselves!" Yumi interprets everything related to women in Iran in a negative way...

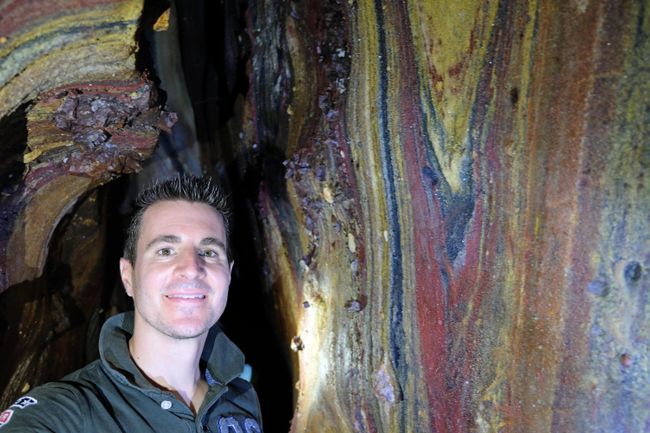

Nevertheless, Marco wonders why Yumi, as a Cuban by birth, doesn't feel more comfortable in Iran. After all, there are remarkably many parallels between Cuba and Iran. Both countries celebrated a round anniversary of their revolution in 2019 (Cuba 60 years of Fidel Castro and Iran 40 years of Ayatollah Khomeini). Both countries have been mortal enemies of the USA since their revolution and are therefore heavily sanctioned, and international credit and debit cards do not work in the country. Therefore, for our entire stay in Iran, just like in Cuba, we have to bring enough cash with us and exchange it into the local currency on-site. Since US President Trump withdrew from the nuclear deal a year ago and imposed new sanctions on Iran, the local currency has collapsed so much that we can benefit from incredibly cheap prices in Iran - unlike in Cuba. A beer or a mojito costs 30-60 cents in an Iranian restaurant, but there's a catch: the drinks do not contain alcohol because it is also prohibited in Iran. Nevertheless, alcohol is consumed in large quantities in Iran every day, just not in public. Here, too, we integrate perfectly when we stay overnight in a camping tent in the desert and take part in a drinking game in front of the campfire. Hossein, a 21-year-old who brought the homemade liquor, explains to us how easy it is to get alcohol: "If you know the right people, you can get alcohol, cannabis, and other drugs delivered to your home within 5 minutes with a phone call. If you don't know anyone and don't have a phone, it will take 10 minutes." Nevertheless, we are surprised when we later learn that Iran is one of the countries with the highest number of drug-related deaths in the world, as many drug-related offenses are punishable by death here, including even the cultivation of cannabis. "About three-quarters of all executions in Iran are carried out for drug offenses," Hossein calmly tells us while smoking a joint and passing it around the campfire.

Anyone who thinks that the Iranian list of prohibitions can't get any longer has forgotten about the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan. During this time, in Iran, among other things, you are not allowed to eat, drink, or smoke from sunrise to sunset. So for a whole month, all Iranian restaurants are closed during the day, and eating/drinking/smoking in public is an absolute taboo. The moon's constellation wants it that way, precisely in our third week in Iran, the month of fasting begins. Devout Muslims must fast for 30 days a year to remember the holy month when their prophet Mohammed received the first verses of the Quran from God. Through fasting, Muslims are supposed to renounce all earthly needs during the day to get closer to Allah. Fortunately, not fasting is about as common in Iran as not believing or drinking and smoking despite the ban. That's why we (of course, only behind closed doors) have a late breakfast every day and can order a delicious lunch at home at any time within 5 minutes.

The longer we are in Iran, the better we understand that the lack of social freedom is not the main problem for the younger generation. Because there is a workaround for virtually every Islamic prohibition. The main problem is of an economic nature, especially since international sanctions have been reintroduced and tightened. In one year, the average wage dropped from 400 to 100 Swiss francs per month, many imported goods have become unaffordable or are no longer available at all. So even couples who want to get married can no longer save for a house or a car, and parents from the broad Iranian middle class have to save on their children's education because they can no longer afford good private schools. Alireza and Masha, two university graduates who are now both 40 years old and have an 8-year-old child, are fortunate enough to have saved for difficult times so that they can leave the country. They recently received permission to emigrate to Sweden, where they can embark on further studies and settle down for the next few years. However, since most Iranians are financially doomed to stay in the country, Hamed, our host in Shiraz, says, "There is unrest among the population. Not only among students and liberal elites but now also among the poor and religious population, who have always supported the Islamic government." Meanwhile, the government is desperately trying to blame the West for the crisis. So we are not surprised when one day in Shiraz, we find ourselves in the middle of a large demonstration where thousands of fully veiled women with their children in tow shout "Down with the USA!" and "Down with Israel!" Hamed shrugs and says that fewer and fewer people are allowing themselves to be put under pressure to participate in such state-organized demonstrations - and that many of them see the government as the cause of the crisis, not the international community.

After 3 weeks in the Islamic Republic and the incredibly many impressions and insights, we are quite happy that we can observe the further development in Iran comfortably from Switzerland... and that here we have to deal with other problems like delayed trains or cows without horns :-) After 9 months and 70,000 kilometers of travel, we are now looking forward to settling down again in Switzerland, not having to live out of a suitcase anymore, and for a change, experiencing something like everyday life and routine!Tsarisa eka Xiphephana xa Mahungu

Nhlamulo

Swiviko swa maendzo Iran