Paraguay: Filadelfia

Nai-publish: 12.01.2019

Mag-subscribe sa Newsletter

Already when we started planning our stay in Paraguay, Jörg had the idea that we could rent a car there. This is mainly because Paraguay is a relatively small country, so only relatively short distances have to be covered. On the other hand, Paraguay does not have any of the big, absolute must-see highlights of the continent, but there are many places and villages worth seeing, for example because of the handicrafts produced there or because of a church or other building. It is very inefficient to reach all these places by public transport, especially if you only want to stay at each place for a very short time. With a car, you are much more flexible and can visit several places in one day. Also, as we would find out, the heat in Paraguay at this time was almost unbearable. An air-conditioned car naturally offers a lot of luxury in that respect, not to mention the luggage that can simply be stuffed into the trunk.

Unfortunately, my Swiss beginner driver's license had already expired in September, and my new, valid driver's license was at home in Switzerland. Stupid. After some back and forth, we decided to give it a try anyway, even with the expired "check" to rent the car. After all, I did have a valid driver's license, I just had an expired card with me. And behold, it was absolutely no problem to rent the car with it. Even during the police check, which we encountered on the first day, no one was interested in the expiration date on my driver's license. On the contrary, the expiration date of the fire extinguisher seemed to be much more important to the police. And so the friendly officer checked off this point on his checklist and then let us continue driving.

First of all, we drove to the town of Filadelfia, which is located in the east of the country in the so-called Chaco, a savannah landscape. The drive to Filadelfia on the Trans-Chaco Route would be our longest stretch, about 460 km. However, the long drive was much more pleasant than expected, as the road is mostly straight and flat through the wilderness, and there is little traffic. So, for example, if you need to overtake a truck, you can easily drive kilometers on the opposite lane. The road quality was also much better than expected. Only towards the end of the route did some terrible pothole fields appear, where the drive became really tedious and exhausting, especially after I had already driven 400 km and was getting tired.

When we stopped at a gas station for a break, we got into a conversation with a truck driver who was traveling with his entire family in the truck. He warned us to be particularly careful in this area. It is not uncommon for vehicles to be attacked here, and there are many people here who do not want to work, he said. Especially around the gas stations, caution is required, as shady characters often lurk here and watch you. And foreigners particularly stand out, especially when they are traveling in a small car like our rented Hyundai. In fact, our little car was by far the smallest among all the passing vehicles. But renting large cars is expensive, and the car rental company assured us that we would be able to get anywhere in Paraguay with this car (which we did). The truck driver told us that he had loaded first quality meat and that he always notified the police patrols by phone when he was on the road or stopping at a gas station for a longer break. After this conversation, we naturally felt only half as comfortable in our own skin and therefore hurried to get to Filadelfia quickly. We only got out of the car at gas stations when it was absolutely necessary, after all, there were attendants everywhere (since our little car only had a very small tank, we had to refuel constantly). Nothing actually happened on the way, but it is always better to be cautious, especially when the locals warn you about such dangers. And we really passed by some tiny settlements along the road where the poverty of the people living here was very evident.

But my biggest fear was hitting a cow or some other animal on the way, as they like to stay along the road here. But luckily, nothing happened in this regard either.

As we finally approached our destination, I had become really tired from driving, suddenly the radio crackled....and then suddenly German Schlager music was playing.

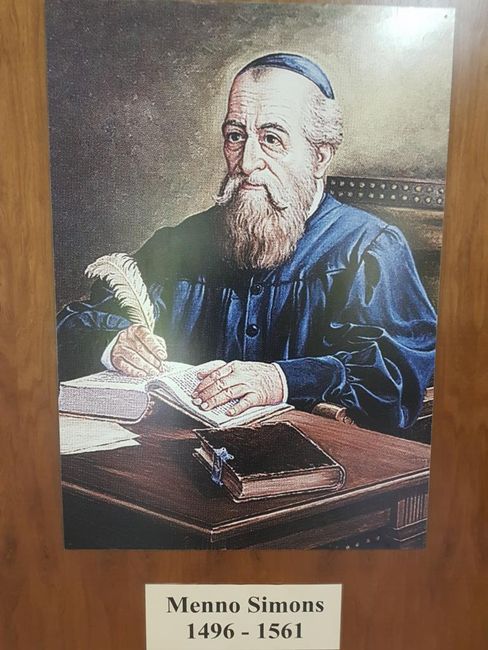

We had come to Filadelfia to visit the Mennonites. The Mennonites are an evangelical free church that traces its roots back to the Anabaptist movements of the Reformation period. The name is derived from Menno Simons (1496-1561), who came from Friesland and was a theologian. After baptism by faith, the Mennonites live according to the following principles:

Honor be to the Father

Honor be to the Son

Honor be to the Holy Spirit

We read the Bible together

We are committed to peace

We gather and celebrate together

We are a global family

Persecution and legal restrictions in Europe, as well as the ban on buying more land for the growing Mennonite families, led to the emigration of Mennonites to Russia between 1715 and 1815, where they were kindly received by the Russian royal family and were granted certain special privileges, for example, they were not required to perform military service, as Mennonites are always pacifists. The Mennonites lived very secluded from other people, stayed among themselves, and followed their old traditions. They were very successful economically, factories were built that produced agricultural machinery for large parts of Russia. The decades before World War I can be described as the heyday of Mennonitism in Russia. Mission work also flourished.

However, the "island mentality" of the Mennonites led to increasing hatred and envy among the otherwise peaceful Russian rural population. Apparently, too few of the Mennonites' spiritual, cultural, and economic goods were passed on to their Russian neighbors.

During World War I and the fall of the Tsar, life changed for the Mennonites. Around 10,000 Mennonite men were conscripted and had to serve as medics or in forestry. The Land Expropriation Law of 1915 hit the Mennonites hard. Robber bands roamed southern Russia, robbing and plundering, torturing, and killing Mennonite men and raping women. Farms were set on fire and entire villages devastated. In 1921, a terrible famine broke out in Russia. In addition, the introduction of communism led to the collectivization of agriculture, and free farming was to be destroyed. Many Russian-German Mennonites were arrested, abused, murdered, or deported to labor camps, where many cruelly perished.

Many Mennonites fled to Canada, Brazil, or Paraguay. From 1930 onwards, the first Mennonites fled to the Chaco in Paraguay, where they could buy a large piece of land from a businessman and founded the Fernheim colony with 13 villages, each with about 25 families. At that time, Paraguay had conflicts with its neighbor Bolivia over the Chaco region and therefore welcomed the settlement of people in this inhospitable zone. Other groups came later and founded the neighboring colonies Menno and Neuland in 1948.

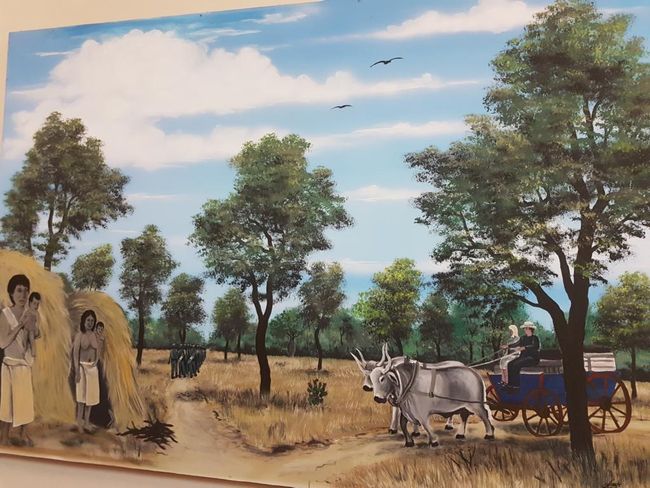

The life of the newcomers in the Chaco was hard. There was only bush here, forests had to be cleared to create arable land, there was not enough food, and the Mennonite settlers also struggled with diseases such as typhoid fever, which many succumbed to. A saying of the Mennonites says: The first generation had death, the second had need, the third had bread.

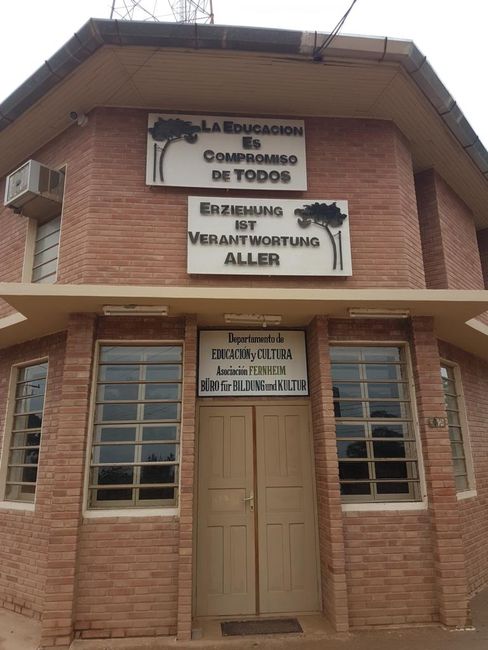

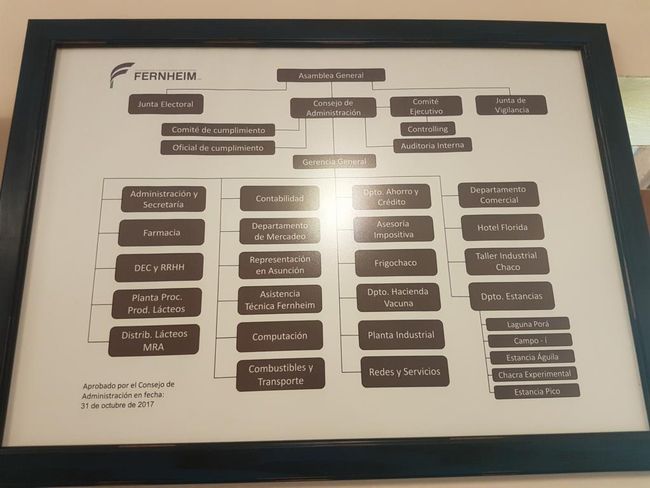

And so it was: Similar to Russia, the Mennonites were also very successful thanks to their diligence. Whenever we spoke to locals in Paraguay about the Mennonites, they always said the same thing: son trabajadores! (They are hard workers). The Mennonites organized themselves into cooperatives within their colonies. Colony houses, schools, hospitals, nursing homes, and a radio station (hence the German Schlager music) were established. Even an airport was built. In 1979, the first villages were connected to the power grid.

In the 1970s, the government of Paraguay decided to industrialize the dairy industry and offered the Mennonites favorable loans to expand their dairies. Nowadays, the Mennonite colonies of Paraguay have a monopoly with more than 75% market share on all dairy products in the country.

In 1956, under pressure from the Mennonites, the construction of the Trans-Chaco Route began. On October 5, 1961, the road reached the Fernheim colony. Since the state could only provide limited funds, the road construction was made possible with funds provided by the Mennonite Central Committee, which had already financially supported the resettlement of the Fernheimers to Paraguay. Among other things, old machines from the Korean War era were donated from the USA and used for road construction. The asphalt of the road from Asuncion to Filadelfia was only completed in 1991, and the last 130 km of the road in northern Paraguay were still not asphalted in 2013. This road has contributed a lot to the development of the Chaco colonies.

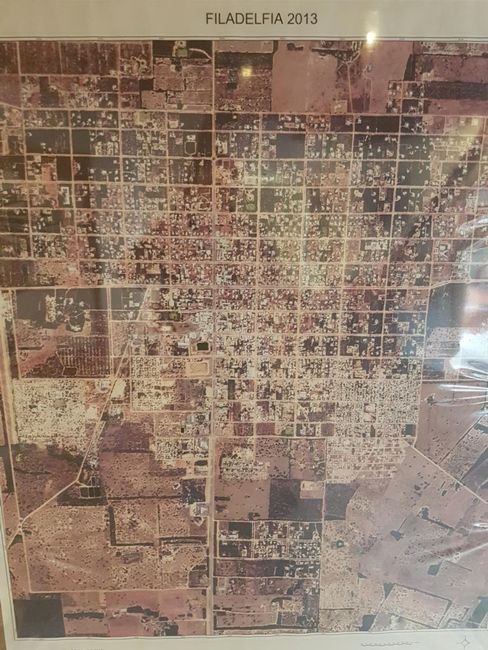

Because now they all came: Indigenous people, Latin Paraguayans, foreign immigrants. They all came here to find work and settle. And there is work here. The cities and colonies grew more and more, there are 18,000 inhabitants in Filadelfia alone today. The Mennonites are already outnumbered. The standard of living is high, in the middle of the savannah of the Chaco. In 1993, Filadelfia was declared the capital of the Department of Boqueron by the central government, and in 2006, the Municipio Filadelfia was established with a municipal administration.

In the Chaco, there are 3 Mennonite colonies: Fernheim with its capital Filadelfia, Menno with its capital Loma Plata, and Neuland with its capital Neu-Halbstadt. But there are also several other Mennonite settlements in the rest of Paraguay. We have seen them. They are hard to miss. Because they look exactly like Laura and Charles Ingalls from "Little House on the Prairie". Still today. The men wear overalls, boots, and hats, the women wear old-fashioned, long flower dresses, braids, and a bonnet on their heads. Not so in the Chaco colonies. The Mennonites here have, according to their own words, learned from their mistakes in Russia, have abandoned the "island mentality," and have opened up to their neighbors and fellow human beings. They live modern lives, wear normal clothes, have a cell phone, and hardly differ from all other people here. Well....except for the blonde hair and blue eyes, that is.

And of course, apart from the fact that they speak German here.

Actually, we were quite amazed when we were approached by a woman who looked very Paraguayan, typically Latino. She spoke to us in German. Not accent-free, but almost perfect German. She explained to us that she had already attended school here, in a school run by the cooperative, and German is taught there. Actually, we had planned to stay at the Hotel Florida, which also belongs to the Mennonite colony, but unfortunately, it was already fully booked. So we had to look for an alternative. We went to the Florida restaurant for dinner and there we also met almost exclusively German-speaking holidaymakers. The only meals available were meat dishes, which is the absolute main food. Each of the 3 Mennonites in the Chaco has its own slaughterhouse.

The next morning, we went to the local tourist information center. The blonde, blue-eyed young lady we met there (unfortunately, I forgot her name) usually works as a sports teacher. But since it was vacation time, she was helping out at the tourist office. First of all, she took us through the museum, which is part of the tourist office, and told us a lot about Mennonite history. She was born here, her family lives in the reserves that have been created by the Mennonites for the indigenous people on their lands, and they work there as missionaries. We really had to restrain ourselves from laughing out loud when we started talking about the Mennonites in Africa, and the young lady began to say something and then said: The Ne-....... uhhhh...Black people.....yeah...apparently political correctness is not yet as important in the Chaco of Paraguay as it is for us. The people here also consistently call the indigenous people "Indians".

Afterwards, we visited the settlers' house, which used to serve as the headquarters of the colony. Today it is also a museum where many of the tools and equipment brought from the old home by the first Mennonite settlers are exhibited, or were donated by the Mennonite Central Committee as a start-up aid. Some fur coats on display were particularly amusing, which people had brought from cold Russia even though they probably never needed them here. There was also a small exhibition in the settlers' house about the construction of the Trans-Chaco Route, where mainly photos from that time were shown.

Already in 1930, a separate magazine was founded, the "Mennoblatt", which was launched in a situation of complete seclusion as a link between the settlement pioneers, and it still exists today. Nowadays, there are about 2,500 subscribers. An old printing press was also exhibited in the museum.

But at 11:30 sharp, the museum was closed, because then everything and everyone in the town closes for lunch. People hurry home from work or school, and the town looks deserted.

In the afternoon, the museums are closed. We passed the time by strolling through the town a bit, looking at the various (honestly not very beautiful) monuments and memorials that were erected on the occasions of the 50th and 75th anniversaries of the colony, and hanging out in the park for a while. We also visited the local library, where you can buy various books in German as well as some books about Mennonite history and culture that have been self-published by them.

We also made a brief visit to the big supermarket of the cooperative. The market was just being built and offers everything you need. There is a kind of "building and hobby department," a clothing store, a pharmacy, and of course a large store with groceries and personal care products. Meat and dairy products naturally come from their own factories, everything else is purchased. The range of products is really extensive, so you don't lack anything here.

For the next day, the lady from the tourist office organized a tour for us, during which we were allowed to visit some of the businesses belonging to the cooperative.

First, we visited the Co-op dairy, which is operated by the Fernheim colony together with the Menno colony. The Neuland colony has its own dairy. Unfortunately, for hygienic reasons, we were not allowed to visit the factory itself. But we were able to walk around the premises, then the head of administration showed us a promotional film, and during the subsequent conversation with him, we got to taste locally produced yogurt. And it was really delicious. The local dairy processes around 75,000 liters of milk per day. All imaginable dairy products in various flavors are produced here and delivered from here to the whole of Paraguay. And that is quite an effort when you consider that the products have to be transported 480 km through the hot Chaco to the distribution center in Asuncion.

Then we went to the desalination plant. Here, the salty water pumped from the ground is treated, which is used in the cooperative's facilities, for example, in the slaughterhouse. The plant comes from Germany and can desalinate 16,000 liters of water per hour. 16,000 liters of fresh water can be produced from 30,000 liters of saltwater. We were even allowed to taste the desalinated water.

Finally, we visited the research and breeding station of the cooperative. Here, on the one hand, vegetable seeds are produced and sold. In addition, breeding animals (horses and cattle) are raised. Farm owners from the surrounding area can have their animals serviced here. Proudly, they took us to the site to admire a huge bottle tree, with which the breeding station has recently won an award. Apart from the fact that I think these bottle trees are generally super cool, this particular specimen was really impressive.

All members of the cooperative contribute a considerable part of their income (I'm not quite sure anymore, but I think it was about 15%) to it. In return, they benefit from some advantages. For example, they can send their children to the cooperative's school free of charge, they receive discounts on products in the supermarket, and they are insured through the cooperative. The members of the cooperative are mainly Mennonites, with few indigenous people or Latin Paraguayans being members. The cooperative still has control over some administrative tasks in the town, such as road construction, hospitals, and other infrastructure projects. The other residents of the community do not pay "municipal taxes," so they can benefit from this infrastructure free of charge, they only pay a little more for gasoline because cooperative members also receive a discount at the cooperative's own gas station. The Mennonites explain to us that they could easily hand over the roads to the government, but they prefer to pay for them themselves, and in return, they have decent roads. And indeed: only the main road in Filadelfia is asphalted, all the side roads are "off-road." But immediately after each rain (and during our visit, it rained several times), a grader drives through the town to repair the roads.

The colony is governed by a mayor and a board of 6 members who are elected for a period of 3 years. The mayor represents the colony and the cooperative internally and externally.

After the tour, we visited the "Indian Museum" for a very short time, which was set up by the indigenous people in the reserves. This is the only museum where all descriptions were only in Spanish. Probably to prevent German-speaking visitors from finding out too clearly that not all indigenous people were so happy about the settlement of the Mennonites in their area. Some indigenous tribes accuse the Mennonites of being responsible for the poor state they are in and that the Mennonites do not help them. They also don't think it's great that people say they don't like to work. After all, they work according to the traditions, customs, and rules of their tribe. Apparently, it all started when the indigenous people begged the newly arrived Mennonites for food, to which they replied that they should first work before they could get something to eat. A simple request was not enough for the Mennonites to give up some of their food. They claim that the Mennonites are to blame for their current poor state because they have cultivated the land and thus destroyed it and also drove away the animals that the indigenous people used to eat. The indigenous people also complain that the Mennonites pay unfair wages, justifying this with poorer knowledge and skills, and that the Mennonites do not respect their respective culture and customs enough.

Even the Mennonite missionary efforts were not always successful. Only a few indigenous people actually converted, and one tribe refused any contact attempts so fiercely that there was even a death, and the Mennonites subsequently gave up.

Well, you can't please everyone. Although the Mennonites bought the land legally and didn't just "steal" it from the indigenous people, the settlement and development certainly did not only bring advantages, and it is quite likely that the indigenous people were disturbed in their way of life and actually robbed of some sources of food. Nevertheless, only a few indigenous people completely reject modern achievements, most of them want these and also benefit from having access to work and infrastructure in the city.

Actually, it is simply a typical European model, the scheme "more skills, more work, diligence, and efficiency = more money and more prosperity". But this exact model ultimately led to the great success of the Mennonites. Son trabajadores. Jörg once said, and although it sounds a bit crude, there is actually something to it that it is incredibly astonishing how the Mennonites have surpassed the rest of Paraguay in just under 90 years. And this, even though they had to start their success story in the most inhospitable and ungrateful corner of the country. Of course, they also had help, especially from the Mennonite Central Committee but also from the Paraguayan state itself. The Mennonites are also all citizens of Paraguay.

And yet they also somehow become victims of their own success. The Mennonites of Fernheim have abandoned their island mentality and accept being in the minority in their community, perhaps they will eventually die out altogether. Already now, a slow mixture is beginning. Our lady from the tourist office could still count the mixed marriages between Mennonites and Paraguayos on one hand, but this trend will increase more and more. Just as religiosity among young, modern people is decreasing, the Mennonites are not immune to this worldwide development either.

And they also depend on people who have moved here to work.

There are also increasingly more problems with crime in the region. The Mennonites are very rich, and wealth always attracts envious people.

However you look at it, you simply have to respect these people for what they have achieved and built here in a relatively short amount of time and for making an important contribution to the well-being of the whole country.

It was an incredibly interesting visit here in Filadelfia, it was very fascinating to get to know these people, and we really enjoyed our time here. We have encountered Mennonites in Belize and we have also met them while traveling in Paraguay and in Brazil. Unfortunately, the majority of them still live in a very old-fashioned and withdrawn manner, so it is difficult to get access to them. So it was all the more exciting to meet "modern" and open-minded Mennonites here, who gave us an insight into their history and way of life.

And so we set off, enriched by another great experience, on the long journey back on the Trans-Chaco Route towards Asuncion. This time we knew roughly where the pothole fields were.

Mag-subscribe sa Newsletter

Sagot (1)

Manuela

Das war super interessant, danke für diesen Beitrag. Du gibst Dir viel Mühe uns an Eurer Reise teilhaben zu lassen, Danke dafür. 😘

Mga ulat sa paglalakbay Paraguay