Bolivia: Jesuit Missions (San Jose de Chiquitos, San Miguel, San Rafael, Santa Ana, San Ignacio)

ప్రచురించబడింది: 29.11.2018

వార్తాలేఖకు సభ్యత్వాన్ని పొందండి

From Santa Cruz, we wanted to visit some of the nearby Jesuit missions, which are a less frequented attraction in Bolivia. However, this turned out to be a rather difficult endeavor.

First, we had planned to take a bus to Concepcion and San Javier. Unfortunately, this plan "fell through" as there was apparently a strike and no buses were running. It seems that the local residents demanded that the government renovate the roads and to achieve this, they blocked them. Public transportation was therefore suspended in solidarity. Strangely enough, we were assured that the roads were passable by private cars. It was also possible to visit the missions on the other side of the circuit by bus. This is a bit strange. The "wealthier" people with their own car could easily travel from A to B, while the less fortunate ones without a car, who rely on the bus, had to suffer. And how is this supposed to motivate the government to renovate the roads? The region is so remote from the rest of the world (about a 7-hour drive from Santa Cruz) that they punished themselves more than the state. And of course, us tourists, but as I said, it is not exactly a frequently traveled area.

In any case, we finally decided to take the train to San Jose de Chiquitos and from there take a bus to other villages. There is actually a functioning railway from Santa Cruz to Corumba on the Bolivian/Brazilian border. There are two types of trains that operate alternately every two days: the cheaper and slower Expreso Oriental and the more expensive, faster, and more comfortable Ferrobus, for which we got tickets. The journey to San Jose took about 6 hours. The train was actually quite comfortable, it was actually identical to one of the "Cama" buses, meaning there were adjustable, quite wide seats with plenty of legroom. In fact, the train is even more comfortable than first class in Switzerland, apart from the constant shaking that lifts you out of your seat, which ruins the whole comfort. When we finally arrived in San Jose at midnight, we realized that there were no taxis. Yay. Although it didn't seem particularly dangerous here, we still didn't feel like wandering around a strange place 2 km in complete darkness with all our luggage and belongings. One of the luggage handlers at the station was kind enough to offer us one of his companions who actually came to pick us up and take us to the hotel. Unfortunately, in all the excitement, we had forgotten to ask about the price beforehand, so the good man naturally asked for a hefty sum for his services. But oh well, at least we were finally at the hotel and could finally rest. Since there are not many hotels in the area and we arrived in the middle of the night, we had no choice but to dig deeper into our wallets and stay at one of the best addresses in town. For a change, we had a really nice room with a comfortable bed, a shower with hot and strong water, air conditioning, and all the amenities. We really enjoyed that.

The next day we slept in and enjoyed ourselves at the breakfast buffet. Then we took a walk around town, ran a few errands (getting money, etc.), and walked back to the train station to buy tickets for the next leg of our journey. Since the "good" train only runs every two days and not at all on Saturdays, we bought tickets for 4 days later. During this time, we planned to visit the other villages with Jesuit missions. In the late afternoon, the Jesuit church of San Jose and the adjacent museum opened, which we visited afterwards.

The Jesuit reductions were settlements founded by Jesuit priests and served to bring together the indigenous population of South America. The main goal was the evangelization and education of the local population. Since the conversion to Christianity did not involve violence in this case, but rather protection from enslavement and other evils of colonial society, the missionary work here was very successful. At the same time, local customs and traditions were accepted, there was no obligation to learn the Spanish language, and only those aspects of local culture that were in stark contrast to Catholic doctrine were changed (e.g. polygamy and cannibalism). The indigenous people were able to govern themselves to a large extent under the leadership of Jesuit priests. More and more indigenous people moved in and could benefit in many ways, e.g. in terms of security and food. The population grew rapidly, with a total of about 100 such reductions, of which there were 10 in Bolivia, with others existing in Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina. Approximately 6,000 people lived in a settlement. The Jesuit reductions were also economically very successful. Each reduction sought its own path to economic success and focused on specific products. Since importing goods from overseas was difficult and expensive, and there was a high demand for necessary goods, the reductions also began to train professionals for sought-after trades.

Everyday life in the missions was highly regulated. Usually, 2 Jesuits led a mission and organized the entire operation. The land (fields for the locals and the community), the buildings, the herds of livestock, and all the facilities of the reductions were basically owned by the entire village community. The yields from the fields, obtained through their own efforts, were the unrestricted property of these families, which they could also use for internal barter. Agricultural tools and livestock were borrowed from the community inventory. Products produced collectively (textiles, meat) were shared fairly.

The fundamental aim of the Jesuits was the conversion of the indigenous people to Christianity, while trying to avoid oppressing them. The spirit of the reductions was ultimately incompatible with the goals of the colonial powers, and the success of the Jesuits created a kind of empire within an empire, provoking hostility and envy from the colonizers. In 1750, the Jesuits were banished and expelled from Spanish possessions in America by royal decree. These events resulted in a progressive economic decline. Some reductions were destroyed as a result, and many residents were sold as slaves. The leadership of other reductions was entrusted to civilian administrators, and the spiritual administration of the reductions was transferred to Franciscans and other clergy. However, the indigenous people did not submit to these new structures and gradually left the reductions, so that most of them were eventually completely abandoned.

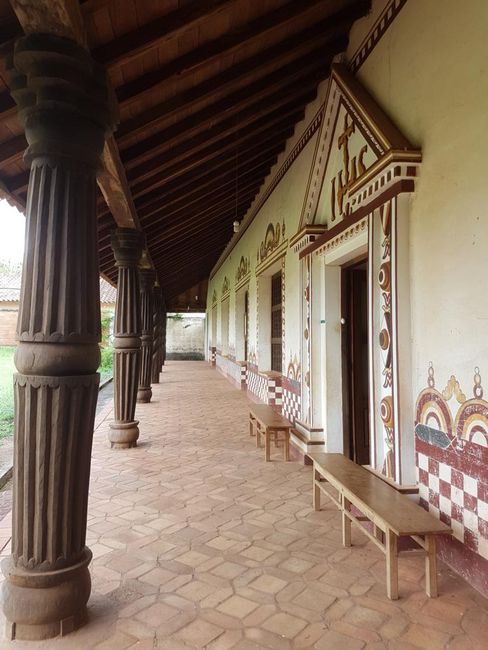

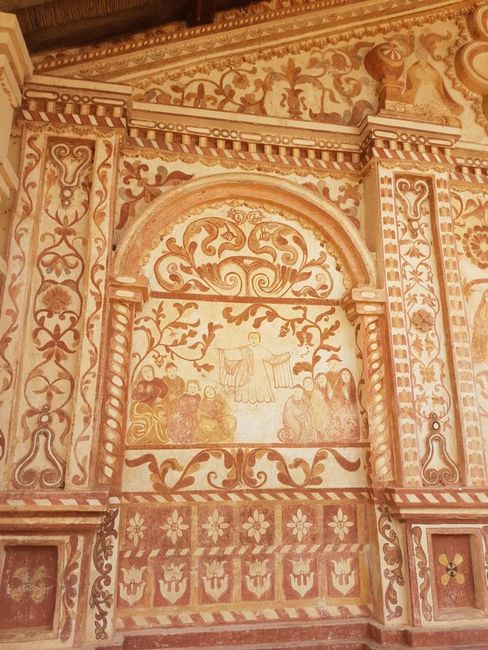

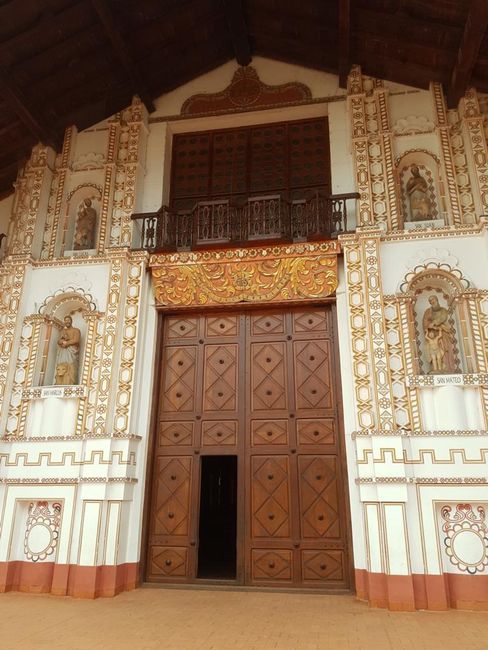

At the center of each reduction was the impressive, three-aisled church with a bell tower, adorned with artwork. It was flanked by the fathers' residence, storage rooms, workshops, and the cemetery. The one-story, solidly built houses of the locals were arranged in rows around the impressive church square. Each house had 4-6 rooms for families of 4-6 people. A typical architectural feature was the arcades/columned corridors in front and behind each house.

Further away were craft workshops, agricultural farms, and the agricultural fields.

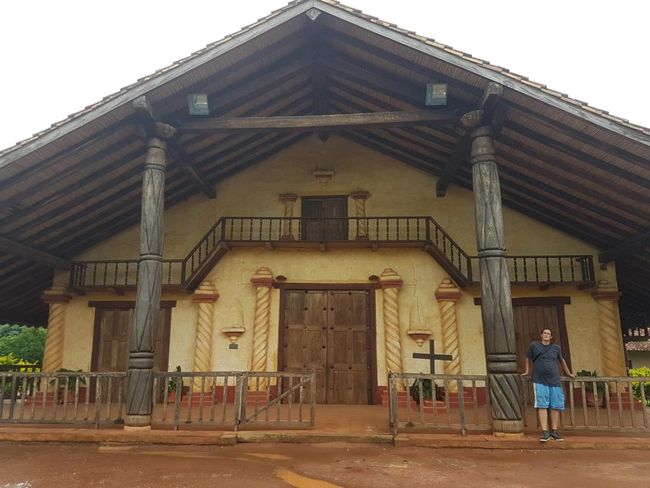

Most of the Jesuit reductions are now just ruins. Only the missions in Bolivia are intact or fully restored and still "in operation". The beautiful churches are still used for worship. The large central squares are green and lively, and the row-like houses are inhabited. The arcades are still everywhere and are still enhanced with elaborately carved columns.

In San Jose, there is a very beautiful stone church from the outside, which is even illuminated in the evening. However, the interior is not particularly stunning. The church grounds also house the museum, which provides some information about the history of the Jesuits, their architecture, and art. In the rooms where the museum is housed, there are also some original wall paintings that were created during various expansion stages.

The next day, we headed to the bus terminal to take a bus to San Ignacio de Velasco, and from there to visit more Jesuit villages. We were quite amazed when we were told at the terminal that the local bus companies were also on strike and would not be going to the villages. Great. What should we do now? After all, we had already booked the train, and that was in 4 days! So we quickly found a taxi and agreed on a price for a 2-day round trip to the Jesuit missions. It was, of course, much more expensive than taking the bus, but we had come here specifically for this and it was out of the question to leave without accomplishing our goal, let alone hang around in San Jose for 4 days. Another advantage of a private driver was that we could travel on our own schedule and were not dependent on unreliable bus lines that only ran once a day. We could also see one more mission than we had originally planned.

The next morning, our driver (unfortunately, we forgot his name) came to pick us up. He was not at all talkative, so we spent most of the driving time looking out the window and enjoying the vast and beautiful landscape.

First, we drove to San Rafael de Velasco. In general, it has to be said that the churches all look pretty similar from the outside. However, some have their own peculiarities. In San Rafael, the interior of the church was definitely the most beautiful of all the churches we had visited. In San Rafael, we also had lunch. All these villages we visited along the way were really tiny little specks in the middle of nowhere, so we obviously stood out like sore thumbs.

Next, we drove to Santa Ana. By now, it had started pouring rain. As if that wasn't bad enough, we arrived to find that the church was closed. Of course, it was about one o'clock in the afternoon...siesta time! We encountered a young man and asked him if it was possible to visit the church, to which he made a phone call and said that the church caretaker would be back from his lunch break around 2:30. In the meantime, the young man, who turned out to be the son of the church caretaker, led us through the small museum, where we could see some dusty artworks from the church, parts of the original decorations, old tools, and agricultural equipment, as well as a bag made from bull testicles. Afterwards, we waited in the park until the caretaker arrived promptly at 3 o'clock. He was an old man who clearly had no hurry. He gave us a brief tour and provided some explanations and comments on the restoration work. In addition to information about the restoration work, he also had some anecdotes and old stories from the time of the Chaco War. Unfortunately, his muttered Spanish was so difficult to understand that we didn't get many details. But he was very warm-hearted and it was clear that he had been involved with this church his whole life, loved it very much, was very proud of his office, and was delighted with every visit. After all, it was the only tour we had received in all the missions.

The highlight here was definitely the organ, which dates back to 1754. However, only the exterior of the instrument remained, the pipes were missing. In 2000, a group of French people came here and renovated the organ, replaced the pipes, and installed an electric air blower, so it can be played again today. And we were very surprised when the caretaker invited us to play a little on the organ. And with the window open, so that all of Santa Ana could hear me playing "alli mini Entli" on the organ from 1754! The caretaker himself could also play some pieces on the instrument that his children and nephews had taught him. So we sat there for a while, listening to him and playing a little ourselves. We really enjoyed the visit to Santa Ana, and although we hardly understood a word of the stories of the sympathetic caretaker, we immediately took a liking to him and of course, left a tip for the warm-hearted tour and the musical entertainment. By the way, the role of the church caretaker has a long tradition in Santa Ana and is passed down from father to son.

Then we continued to San Ignacio, where we spent the night. First, we found a hotel and arranged with our taxi driver to pick us up at the hotel around noon the next day. In the evening, we strolled around town and visited the local Jesuit church. Interestingly, the original church was demolished and replaced by a modern one. Later, the officials realized what they had done and restored the new church to its original state. However, since it is a modern building, unlike the others, it does not belong to the UNESCO World Heritage Site. The church was nice, but it had nothing extraordinary to offer compared to the others. And when the evening service started, we decided to leave anyway. Actually, we had planned to explore the town and maybe drive to the small lake nearby the next morning. However, severe stomach problems began to plague us during the night. The lunch we had at the shabby pub in San Rafael the day before was probably not a very good idea. I'll spare you the details, suffice to say that after a night alternating on the toilet, we didn't feel much like sightseeing anymore. When the driver picked us up, he kindly took us to the lake for a brief look, so that we could at least take a brief glimpse of the landscape, which was not particularly breathtaking. He also offered to visit the local caves, but we gladly declined that option given our condition.

Then we continued to San Miguel. Once again, we arrived at the most inconvenient time, so the church was closed again. So we sat down in the park and waited for the siesta to end. Now we had already gone through all the trouble to come here, so we certainly wouldn't leave again without visiting the church! Apparently, our driver found it too annoying to sit around and wait for hours again, so he somehow managed to find someone to briefly open the church for us. This church was nice too, but it also had nothing particularly remarkable to offer.

After this final visit, we headed back to San Jose de Chiquitos. It should be mentioned that all the roads in this area are "off-road", there is no asphalt to be found here. In the evening, you have a nice shaking trauma in the back of your neck, and your behind hurts a lot.

The next day, our train to the Bolivian border would leave, but not until 11:30 p.m. So we had another day ahead of us, during which we would hang out in San Jose. We decided to go on a hike to the surrounding "attractions". In fact, these are the ruins of the old city of Santa Cruz, at its original location. Apart from a few walls sticking out of the ground, there is not much to see. Then we went uphill a bit to a viewpoint where you had a nice view of the forests and the town of San Jose. The last stop was at Valle de la Luna, where the surroundings resembled a lunar landscape. There was a small chapel and some figures of saints perched on a few rocks. All in all, it was not particularly stunning, so it's definitely not worth coming to San Jose for that.

The best part of the story is yet to come. In the evening, we (way too early) arrived at the train station and waited for our train. We handed over our luggage to the baggage claim and explicitly indicated "TO QUIJARRO!" In the meantime, the train station filled with countless people. At some point, a train arrived that had a striking resemblance to the luxurious Ferrobus train we had come on. Since the train appeared to be empty at first glance and no one made any attempt to board, we asked the conductor if that was the train to Quijarro? No, no, he said, another train is coming. Okay, we thought, the train left and we waited. Shortly thereafter, an incredible piece of junk train arrived, and all the locals hurried to board it. Something wasn't right here. We went to the conductor again and it turned out that this was the second-class train to Santa Cruz, obviously with a few hours of delay. As it slowly dawned on him that we should have actually boarded the first train, he widened his eyes, asked us to wait, and hurried off to the control room. Just at the right moment, we were able to stop the baggage handlers before they loaded our luggage onto the Santa Cruz train. This was unbelievable!!! In my mind's eye, I already saw ourselves either hanging around in San Jose for another 2 days or driving the next 8-9 hours to the border in the piece of junk train. The only hope was that there was a bus on this route that was not on strike. But something happened that we really absolutely did not expect: they actually brought back the damn train! We were quickly stuffed into a car with our luggage, which took us to the next level crossing after the station. There we waited for the returning train to pick us up again and set off once again on the journey to Quijarro. Just imagine going to the conductor at Aarau train station and asking him to bring back the missed express train to Zurich. I'd love to see his face.

And after another 9 hours of shaking and rattling, we arrived at the Bolivian/Brazilian border in the early morning and continued on to Brazil after almost 7 weeks in Bolivia.

So that was our time in Bolivia and I have to say, I really liked the country. I can't even say exactly why, but I found it likable here and felt very comfortable. A friend of mine who traveled to the country a few years ago told me that she often felt the people were a little racist and didn't like foreigners very much. This did not come true for me at all. The people are somewhat reserved and don't approach you very much, but I always felt welcome everywhere and had some very interesting encounters and conversations with locals. There is also a lot to see in the country, so you definitely won't get bored. I was surprised how touristy the country is, it was certainly different a few years ago. Nowadays, there is already a well-trodden gringo trail, at least between the major tourist attractions of Sucre-Potosi-Uyuni-La Paz-Titicaca Lake. It is accordingly easy to get around between these points, the buses are decent, and there are good connections. There are tour operators everywhere where you can book day trips easily and at short notice, and the hotels are very affordable. Spanish language skills are certainly a great advantage if you want to travel in the country. Very few people speak English, and a tour with an English-speaking guide in Uyuni, for example, immediately costs twice as much.

It becomes a bit more difficult once you leave this gringo trail. Then it becomes either difficult, expensive, or both. We saw this in Torotoro, Vallegrande, and at the Jesuit missions. Especially regarding transportation, either you travel in extremely bumpy buses that offer no comfort at all and endure long travel times with countless stops, or you hire private transportation, which, due to the sometimes very poor road conditions, costs a lot of money. Guides and tours, if available at all, are also more expensive, the same goes for hotels. However, you can visit beautiful places that are (still) not completely overrun and feel like you're back among the locals. And driving for hours in a stuffy bus next to a sack full of cackling chickens, while listening to a fervent seller of dubious medications and observing the constant flow of locals getting on and off every few meters, really brings out the true Latin American feeling.

వార్తాలేఖకు సభ్యత్వాన్ని పొందండి

సమాధానం

బొలీవియా ప్రయాణ నివేదికలు