Searching and Finding at the Sikorski Institute or: A Glimpse into Polish London

شايع ٿيل: 01.07.2023

نيوز ليٽر جي رڪنيت حاصل ڪريو

The Sikorski Institute in London is one of the major Polish exile archives and also a museum.

Sikorski - the initial 'S' is pronounced more like a soft version of 'Sch' in German - was Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile between 1939 and 1943. He died in a plane crash on his way back from a trip to Polish soldiers in the Middle East. His death, and whether it was an accident or initiated by the Soviets, remains controversial in Polish society to this day. Sikorski has become a symbolic figure, a myth of Polish suffering, but also of heroism. Many DP camps - including the one in Flossenbürg in which I work - deliberately named themselves after General Władysław Sikorski, which eventually became the namesake of the institute.

On my second day at the Sikorski Institute, I found the private estate of one of the central DPs I work on. I couldn't believe my eyes after spending hours searching through the finding aids. Leafing through, reading, reading, leafing through, scrolling, reading, scrolling.

Not much has been digitized here (yet?), so there is a lot of 'manual work' necessary. Literally: reading, reading, leafing through, scrolling, reading, scrolling, and going back: wasn't that a name that sounded familiar to me?

So I checked in my research database ---- takes a moment, entering, searching, looking up; no results, it was just a similar name.

Back to the finding aids, leafing through, reading, reading, leafing through, scrolling, reading again.

And then: Yes, it's true, S.P., let's call him: Stanisław, the temporary DP commander of Flossenbürg, the head of the Polish DP self-government. The DP camps - camp is the English word for camp - were under the control of the respective military administration. Flossenbürg is in Bavaria, where it was the US military government. The international relief organization UNRRA was responsible for all DP camps: UNRRA - English for "United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration". This organization decided that the internal administration of the DP camps should be carried out by "their own people", i.e., the DPs themselves. This was intended to ensure a smoother cooperation between the UNRRA staff, the military government, and the respective DPs, both linguistically and culturally. However, misunderstandings, disputes, and conflicts often arose despite these efforts.

So: Stanisław's estate - amazing!

Order it.

And definitely ask the archivist Paulina to present it to me today and not just on my next visit because the weekend is coming up.

Waiting for the files.

Takes time.

I wonder what's in there? And how big will the estate be? It's not apparent from the finding aids. So I'll just have to wait.

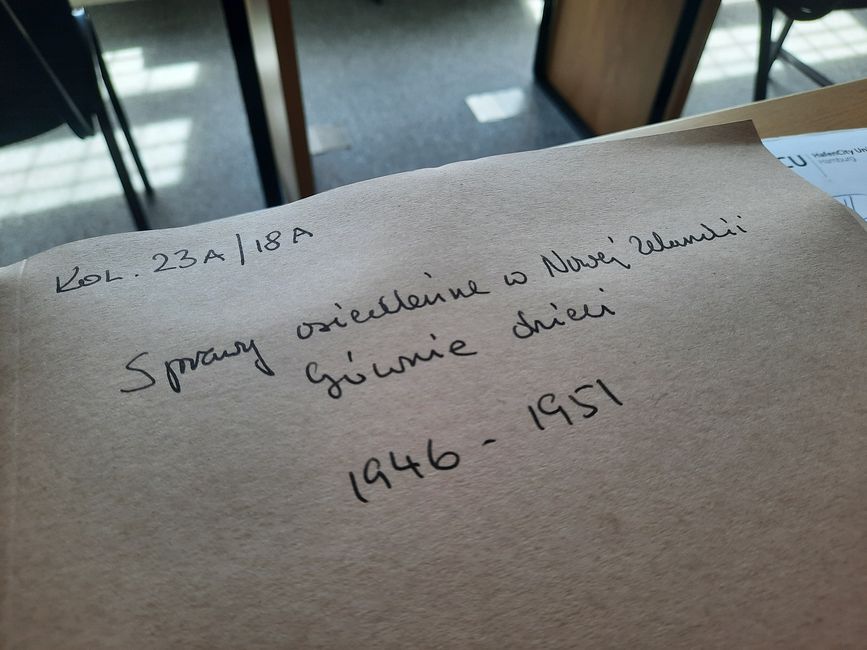

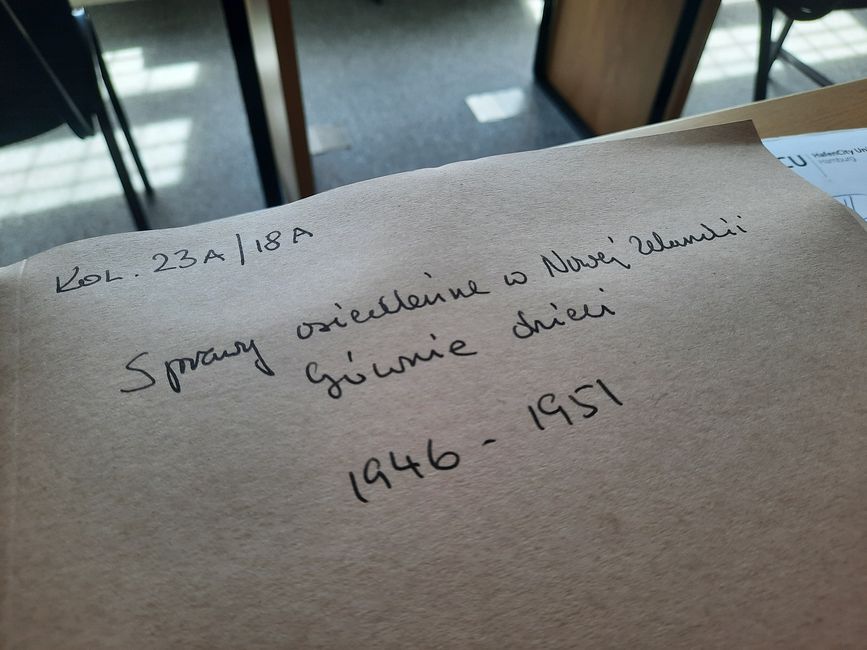

During the waiting time, out of interest, I set aside a few other files, including those about Polish children who came to New Zealand in 1944 through the Soviet Union and Persia. No, it's not directly related to my thesis, to be honest, it has nothing to do with it. But somehow it brought everything full circle for me:

During my Work&Travel in New Zealand in 2008, I came across an English-language book about the 'Polish children of Pahīatua' in a hostel exchange shelf in Wellington. There is even a monument and a small museum in the Wellington Harbour.

Unfortunately, I don't remember the title of the book that impressed me so much. At the time, I was so excited about it that I gave it to a fellow traveler, I think she was a prospective teacher from Regensburg, and I even had the thought, "I won't forget the title of this book for sure!"

Well, I forgot.

I also don't remember the name of the person I traveled with from Regensburg, and we are no longer in touch. With the end of StudiVZ - was that its name? - the loose connection to her also ended. I would love to write to her now. I wonder what she's doing these days? Did she even read the book from back then?

But the subject stayed with me, at least. And if I want to make a big leap, I could say that's why I'm doing my PhD on Displaced Persons now. And why I'm heading back to Down Under. It sounds incredibly straightforward - some would say 'nice.' But I'm enough of a historian to view this linearity with skepticism: I know all the detours and side paths. It wasn't and isn't that simple. Nevertheless, the story above is somehow nice, especially since it occurred to me while thinking about the title of that book and sitting in front of these files at the Sikorski Institute, that I am now a doctoral candidate at the University of Regensburg. It's a crazy and funny coincidence, and it made me smile.

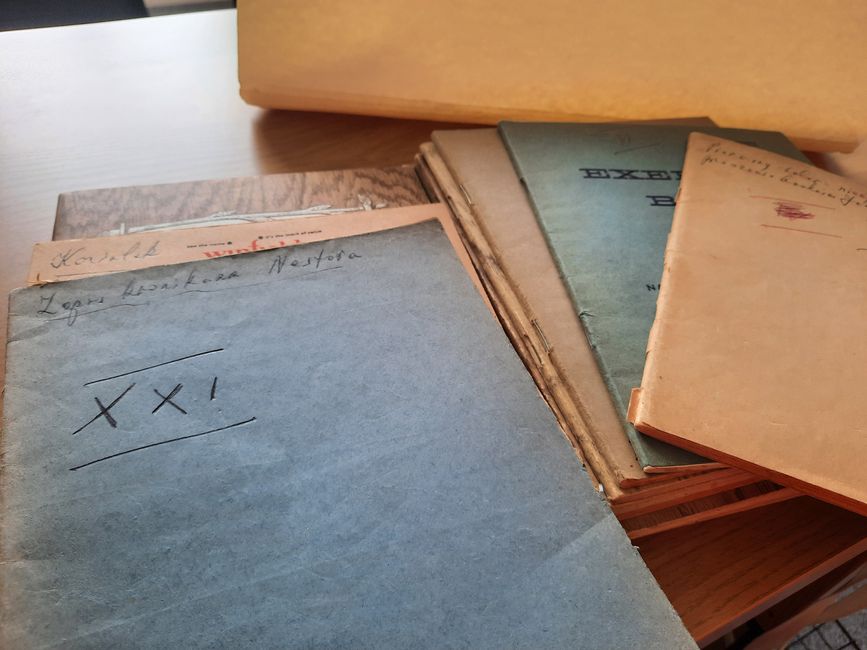

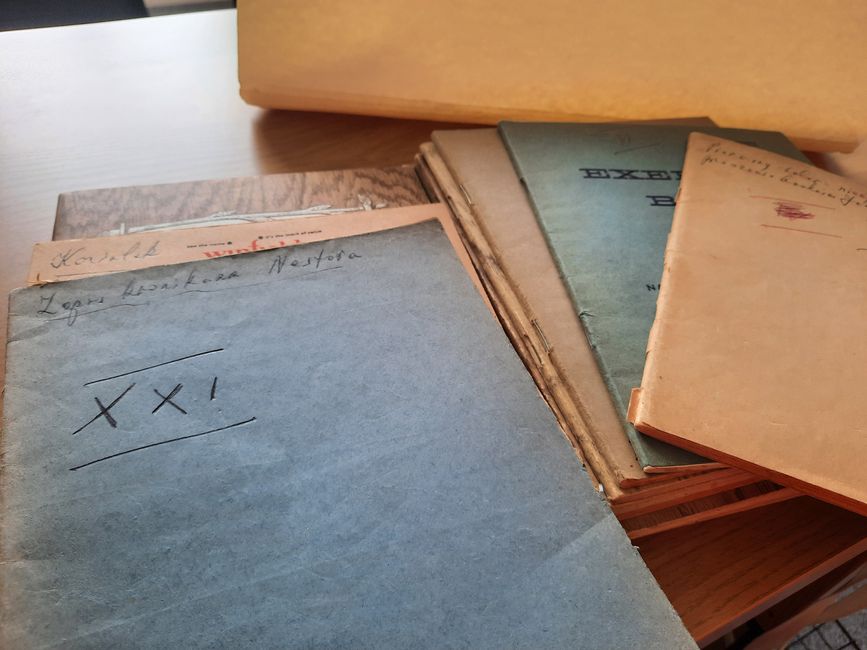

File folders from the Sikorski Institute in London about the settlement of Polish children in New Zealand, 1946-1951. For more information and photos, visit: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/page/polish-refugees-land-new-zealand

But back to Stanisław!

His estate consists of English language learning books and transcripts of Polish exile newspapers. He was an intellectual, extremely interested in political events, even and perhaps especially in exile, even before and during the German occupation of Poland, he was politically active. He remained so even after, in London exile.

He apparently continued to learn English even after 30 years in Great Britain; he also learned the English translations of fish species - maybe he was a fisherman? Poland obviously remained a place of longing for him: transcripts of bus timetables and other connections between London and Poland in the early 1970s. Whether he ever went back there? I don't know.

And what is there in his estate about his time as a DP?

Zero, nothing!

I felt a certain disappointment, that can't be true!

With some distance: Of course. That's part of it and everyone who works in this field knows it. But I found other exciting things related to my work. I can't reveal everything here (yet) - it will be in my book in a few years.

How do you even know where to find things about these people?

I can't write about that here and for now, it remains my 'trade secret'.

Just this much: I was able to use the Covid lockdowns to research about 2,300 people registered in the DP camp Flossenbürg. Yes, I didn't have much to do during that time and had the thought on the first day of the lockdown: now or never. And I started researching each individual name I found related to the DP camp Flossenbürg, and I was able to trace those paths quite well. I found a lot of information about some of them, and I was able to contact their descendants. Many of them had time during the lockdown and were interested in helping me. Some were already clearing out their attics, so my request came at just the right time.

In 2021, I had a small online meeting with seven descendants who live in the USA, England, Germany, Australia, and Poland - by the way, scheduling the time was insane! :D Some in the early morning, some in the late evening, and us in Europe somewhere in between. Still, we were together for at least an hour, and those who wanted to shared family photos or whatever they had. It was fun, beautiful, and at the beginning - also linguistically - a little strange: Which language are we even using? Some could only speak (or still speak) little Polish, some spoke a little German as a foreign language but barely any English. With some laughter and mutual translation, it worked out, and eventually, it became a Polish-English mishmash. Back then, Monika was also there, a granddaughter who now lives near London. And I'm on my way to visit her now.

Postscript on the museum:

If I understood correctly, the Sikorski Institute's museum is visited by about 13,000 people per year. According to the visitor book, mainly people from Poland or Polish people who are currently in London. During my stay, there was also a larger motorcycle group there, undertaking a memorial ride in the name of Sikorski. A visit there is interesting, especially if you want to look at many uniforms, weapons, standards, and flags.

Actually, they would like to overhaul and modernize the museum, but there is no money for that, not even from Poland, as I was told on-site. So the museum seems a bit outdated. Although, of course, I still took a look with great interest. Since I have been dealing with DPs from Poland, I have also been interested in the Polish army and particularly the Polish units that fought alongside the Western Allies.

I was proudly shown the museum's highlights: the original flag supposedly flown over Monte Cassino, the table where the Polish government in exile met in London, and the workplace of Władysław Anders. I could say a lot more about Monte Cassino and Władysław Anders, but then this post would be too long - and I want to go to Monika now.

نيوز ليٽر جي رڪنيت حاصل ڪريو

جواب

سفر جون رپورٽون برطانيه