Food Distribution

Опубликовано: 16.11.2022

Подписаться на новостную рассылку

In the first week of the month, food rations distribution takes place in the refugee camp.

The camp is divided into a total of 4 camps, Kakuma 1-4, and there are 3 food distribution centers. The food distribution center in Kakuma 1 is operated by LOKADO (the NGO I am interning with) on behalf of UNHCR and the World Food Programme. Kakuma 1 is the oldest camp, with refugees living there since 1992, some of them now in the 3rd or even 4th generation. The 'Lost boys of Sudan' were the first to be admitted. They were young boys, without parents, who had to flee before the civil war in southern Sudan. For several years, they lived in Ethiopia under precarious conditions, walking 1000 miles on foot. Out of the survivors, 10,000 boys arrived in Kakuma. 4000 of them have been resettled in the United States in recent years. Today, more than 22 nationalities live in the camp, over half of the 188,000 people come from South Sudan. Somalis make up about 1/3 of the refugees. Some come from Congo, Ethiopia, Burundi, etc.

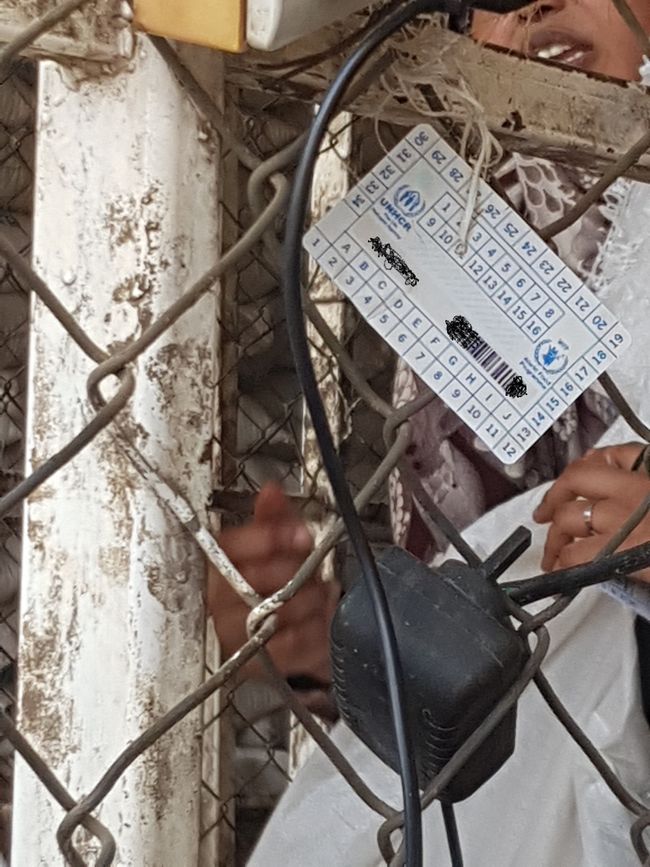

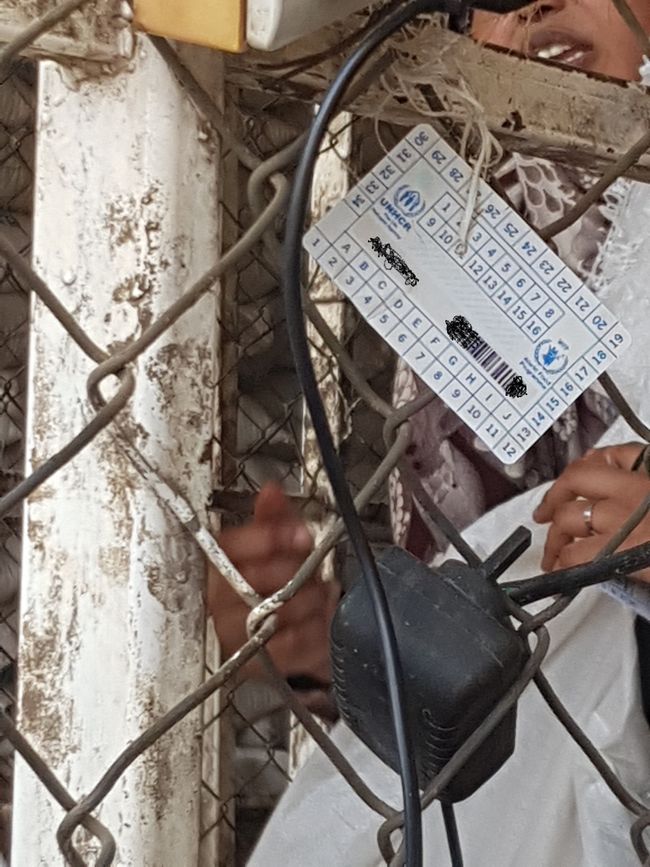

In Kakuma 1 alone, more than 65,000 people are provided with food on 5-7 days. I was able to work there for two days. One person from each household comes to collect the food. In Kakuma 1, there are nearly 14,000 households that picked up maize, cooking oil, and red beans or other legumes for November. Additionally, high-calorie peanut paste was given for young children. 14,000 people in a few days are a logistical challenge! People sometimes wait in front of the distribution center as early as 5 in the morning, then they give digital fingerprints like at the airport and show their food distribution card, which is marked with a barcode and provides data on how many people are in the household. This is to ensure that each household only collects its food ration once. In the past, there have been tricks played and the food was then sold, especially to the local Turkana population, who do not receive food rations. After registration, the rations are measured according to household size in a total of 6 distribution rows. Households with over 20 people are not uncommon. This month, each person received 6.3 kg of maize, 1.8 kg of beans, and 1.05 liters of oil. For a household of 20 people, that quickly adds up to a total weight of 183 kg that needs to be transported. Over the years, the rations have become less. The Ukrainian war and unpredictable weather events causing crop failures are also noticeable here. One of my colleagues said that a few years ago there used to be meat and noodles for the refugees. According to him, the food rations are being reduced to make the refugees less dependent so that they are forced to take care of their own food. He thinks that the mindset of the refugees needs to be changed, that they should not become so dependent. I wonder what food security would look like if tons of food shipments didn't arrive here, if organizations didn't take over the logistics to ensure that each household is provided with food (or at least the basics). Additionally, each person receives about 5 euros per month to get additional food from certain shops. The so-called Bamba Chakula money is loaded onto the SIM card and can only be used at certain shops in the camp. If you're unlucky, you wait the whole day, don't get served, and have to wait again the next day.

Here is a brief explanation of how bamba chakula works! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0G-M4tZVtw

Kakuma Refugee Camp is overcrowded. The camp was designed for 70,000 people. It was not intended to be a permanent 'home' for decades. But this year, it celebrated its 30th anniversary, with infrastructure that has solidified a strong dependency on 'aid organizations'.

In recent years, there have been efforts to open an alternative camp, which has space for 60,000 more refugees and focuses on better integrating refugees into the host community of Turkana and promoting more self-reliance. The project is called Kalobeyei Integrated Settlement and follows the KISDEP (Kalobeyei Integrated Socio-Economic Development Plan). Currently, 45,000 people live in the settlement, with new refugees arriving every day.

In Kalobeyei, there are no food rations being distributed. Everything is done through cash transfer, i.e., money-based payment systems. Additionally, the houses are built of stone, with small gardens on the outside for self-sufficiency. It looks more like a village. There are also community gardens and huge greenhouses for people to grow their own fruits and vegetables. Kalobeyei is an attempt to create a long-term settlement that is independent of international organizations in the long run. This also involves helping small businesses and startups to establish themselves. And it aims to promote both refugees and Turkana without creating parallel structures.

In the past few days, I have been with a team from Lokado in Kalobeyei collecting data on how the distribution of firewood and tree seedlings is going. We interviewed both individuals and schools and a hospital in Kalobeyei about the challenges (always irrigation), how many trees have survived, whether they have enough firewood, etc. Firewood used to be distributed to households in the past, but now only institutions receive it. This has resulted in refugees going to cut down trees themselves. There are no longer any trees growing near the camp. The host community complains about this, and it leads to tensions. Their suggestion is for organizations to bring dead, dry wood from the hills and distribute it, so that no more trees are cut down. A Turkana woman with a lot of understanding for the refugees said, "They have no firewood but food. How are they supposed to cook without wood? Are they supposed to eat cold, dry maize? Meat without frying it?'

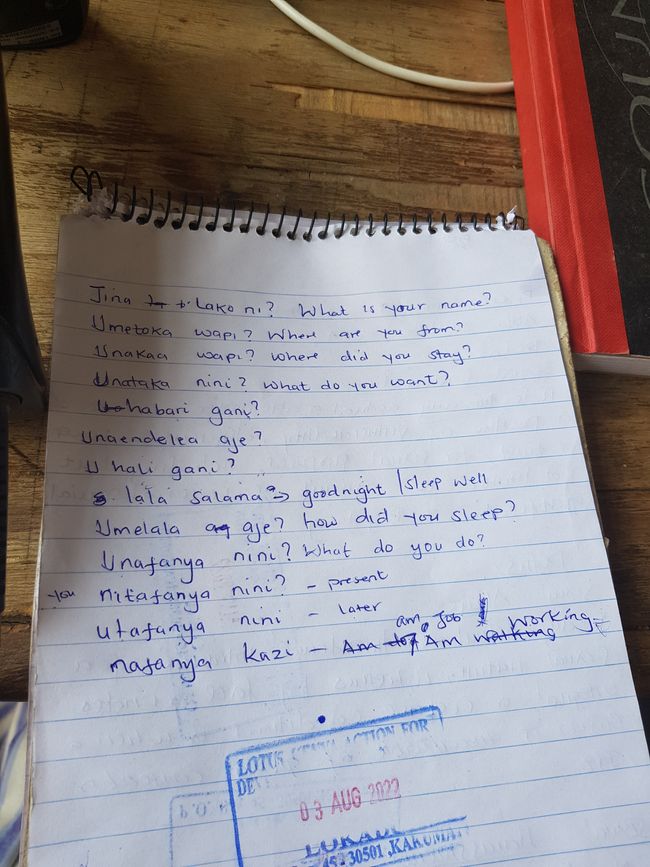

My life in Kakuma has become very ordinary. In the morning at 7:30, I sleepily wait for the LOKADO Land Rover. Sometimes for an hour – then I curse the alarm clock and that I was so punctual. But breakfast makes up for it - I could dive into the sweet white chai.

If I'm not in the office, I go to the field with a group (those are my favorite days). We are brought back at 5:30 p.m. Then three times a week, I treat myself to 2 hours of Afro dance, aerobics, lightweight training, and yoga, in most cases at a stable 35°C, and then I spend the evening either in Cairo Hotel or in the only club-like venue Nakosi with DJs. And the next 2-3 days with intense muscle soreness.

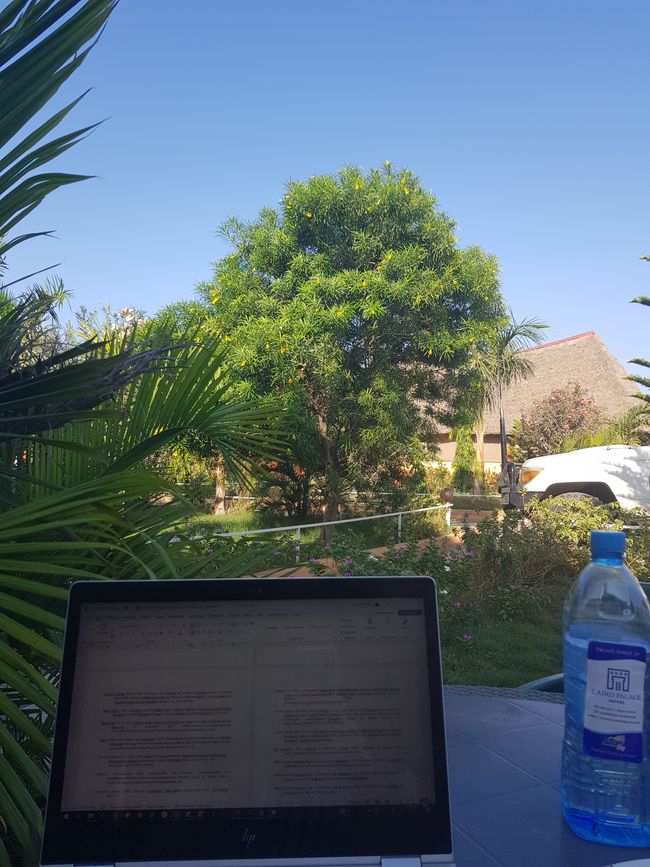

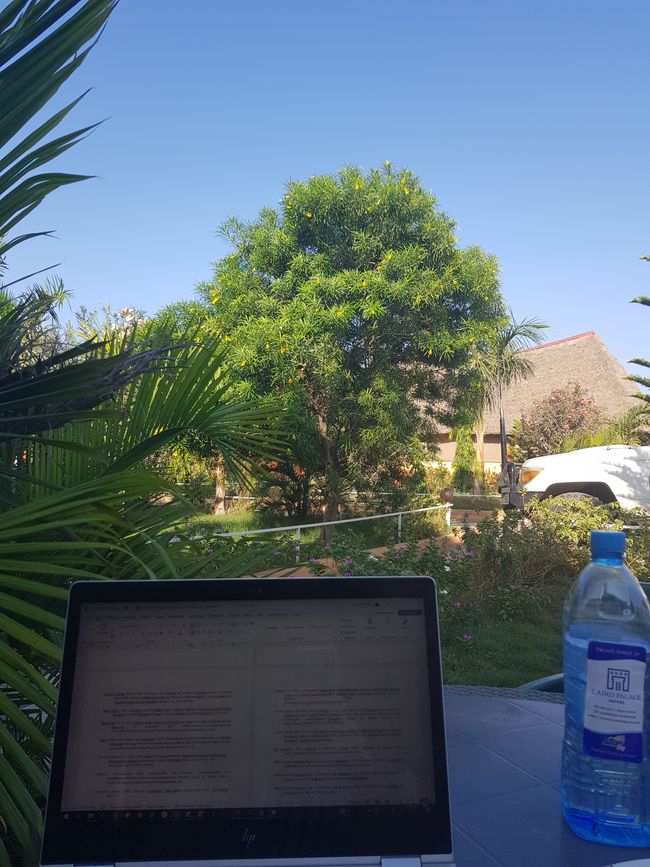

At Cairo, I meet other researchers, people working for UNHCR or other organizations... It is a place for the whites and the 'rich', and here you can even get pizza, burgers, and ice cream - at European prices. For me, Cairo has become my replacement library because I can't motivate myself to sit at the laptop in the guesthouse most of the time. Since many people work at Cairo, it feels like a coworking space, and there are also delicious juices and smoothies for refreshment.

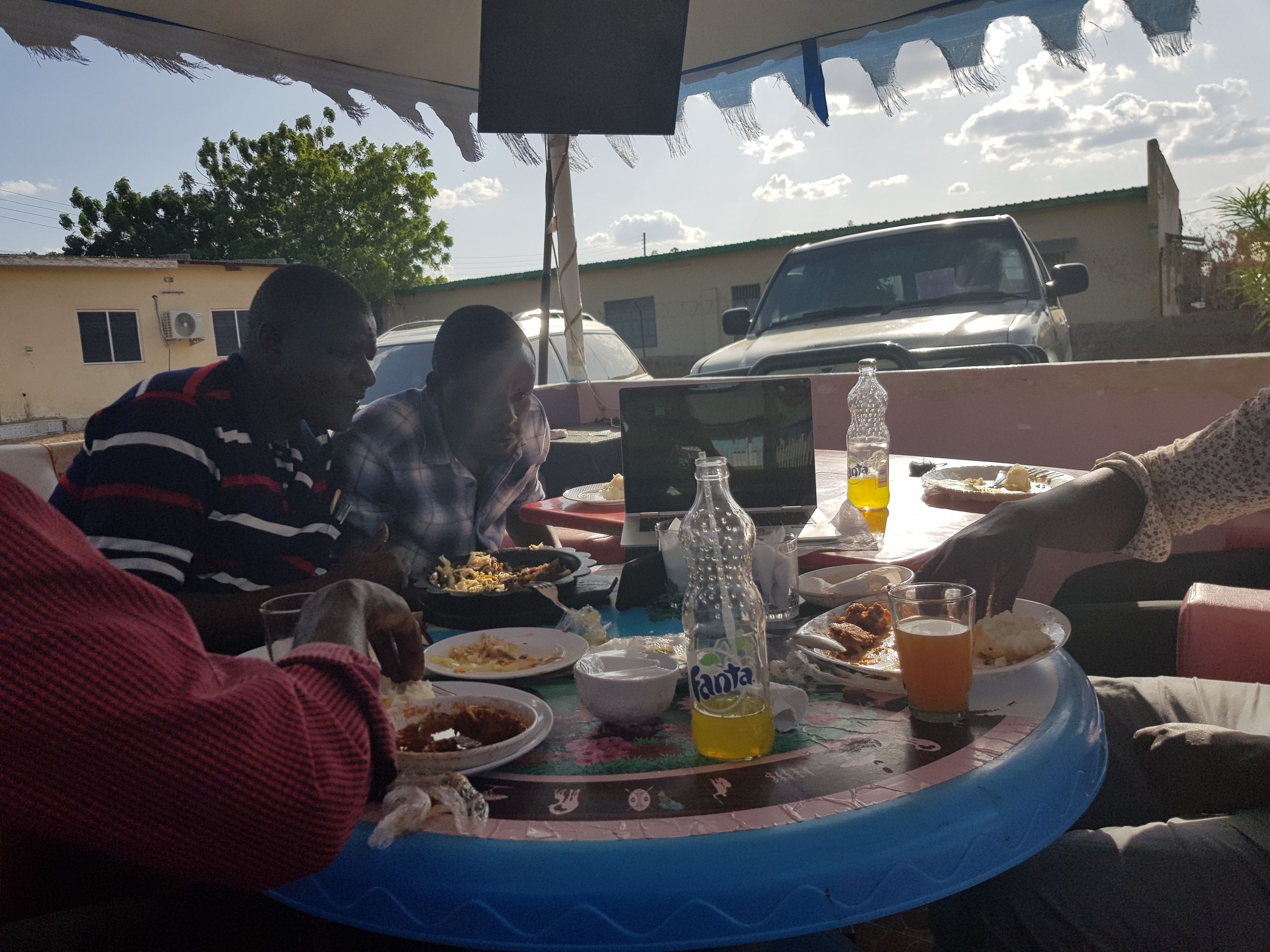

It's a bit of a parallel universe, with a huge truck delivering water every day. There are so many plants growing here, the grass is so lush green. There is a lack of water everywhere else. It's pretty absurd what money can do... Nakosi is more like a desert and a run-down, huge courtyard with plastic chairs - it belongs to a high-ranking politician. It often seems that politicians use restaurants and hotels to launder their money. And it also feels wrong to pour even more money into the pocket of an already rich man, when I could go to all the small, local restaurants to eat.

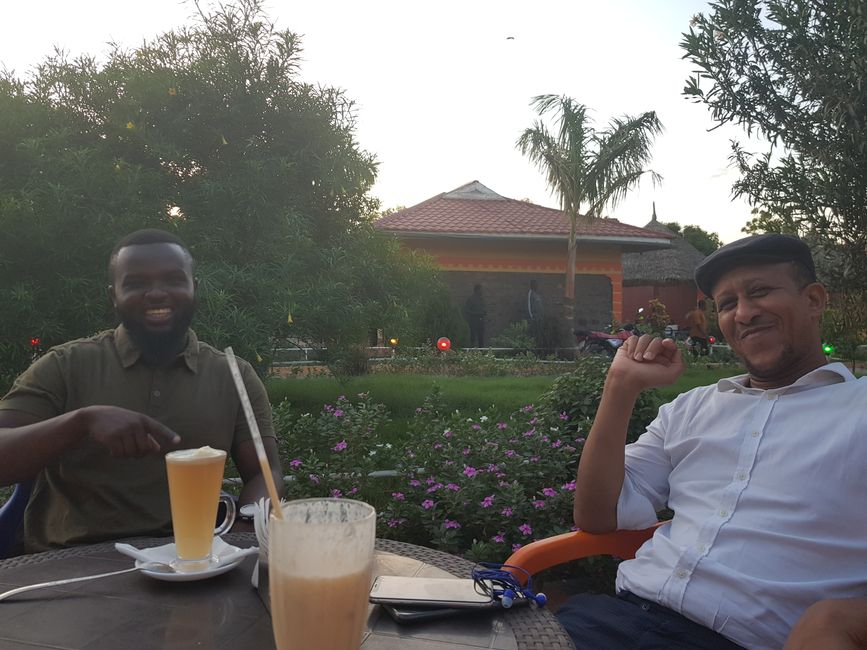

Almost every evening, I sit alone at a table in Cairo and get to know so many interesting new people. It's really great. Most of them only stay in Kakuma for a short time, but I have gotten used to enjoying the moment and knowing that there will surely be other fascinating people coming tomorrow. "Cairo produces wazungus (white people), they just pop up here like mushrooms every day." In the past few days, I have met a poet from the refugee camp here, who processes his traumas in his poems and reports on the stagnation and lack of prospects in the camp. And an activist from Nairobi who travels around the world from conference to conference to advocate for educational justice. And yes, there is also activist burnout here, maybe even more so because the climate crisis, injustice, and lack of opportunities in the education system... are much more visible. We observe the disconnectedness of decision-makers who celebrate with champagne bottles when they have done something "good for the poor" and are so far away from the reality of people's lives, unable to empathize. How stories of refugees are brought halfway around the world (and refugees are allowed to speak in Davos) and in the end, they exploit their stories to create beautiful success stories, but in the end, the person is just returned to the same perspectiveless place in the camp.

I was particularly excited to meet a scientist whom I read and quoted in my last research paper. Like a little fangirl (I only needed the t-shirt with his face on it), I was initially intimidated, but somehow Kakuma breaks hierarchies and so we had very relaxed conversations about life and people and our research here.

In Kakuma, the whole world comes together - I have met people from 5 different continents here, from Libya to Australia, India and Pakistan, England to the USA.

It is rainy season. Actually. The seasonal river is still dry. Last night, there was 5 minutes of rain - far too little. And that for the first time in weeks. We wait, the desperation and concern grow. Everyone knows it won't come. Again. And somehow, there is still hope for a miracle here. The heat is really unbearable on some days. A friend said to me, "If this is Kakuma, imagine hell!"

Warm greetings

Franzi

Подписаться на новостную рассылку

Отвечать

Отчеты о поездках Кения