ausderfernebetrachtet

vakantio.de/geschichtenvonunterwegs

La Paz

Gepubliceerd: 17.10.2024

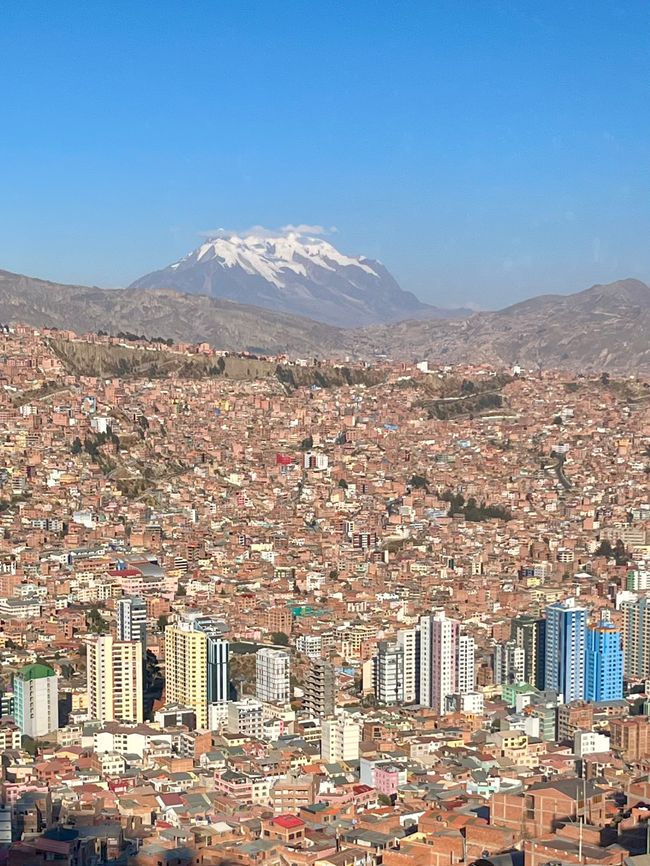

La Paz as well. Puhhh. What a city and how incredibly difficult it is to somehow bring the impressions to paper in an orderly manner. This is really a challenge, and I don’t know how to even begin summarizing it. Overall, I spent more or less over 2 weeks in this chaos, and I will try to summarize it somehow. When you arrive in the city for the first time in the middle of the night, what stands out first is the incredible dimension of the urban space. You drive over El Alto into the valley and only see lights on the horizon. Houses, hills, and an unfathomable populated area in this seemingly hostile environment at an altitude of 4,000 meters. La Paz describes only the core city located in the valley. However, right next to it is El Alto. Formerly a district of La Paz located on a plateau above the city, El Alto is now an independent municipality with an estimated population between 850,000 and 1 million (as El Alto expands daily, the exact number of residents can only be roughly estimated). While the more affluent parts of the population settled in the sheltered valley, El Alto is rather a melting pot for people who can no longer afford to live in the supposedly better-situated valley. El Alto is a city with a very high proportion of indigenous population, and a large portion of the people have migrated from the Altiplano to El Alto in recent decades due to rural flight and poverty. As a visitor, you immediately feel the stark contrast between the more middle-class La Paz and the relatively impoverished El Alto. Looking from the streets of La Paz towards El Alto, you only notice the mountain ridge at the edge of the city, and it’s hard to realize that a much larger city still stretches beyond the city’s borders on the plateau. It seems completely surreal how the two municipalities entangle themselves in a kind of symbiosis. From the perspective of El Alto, however, during a ride on the Teleferico or while walking along the edge of El Alto, you gaze into the valley basin, and it is difficult to grasp the scale of the core city in the valley. Everything feels so surreal that you really have to remind yourself repeatedly that you are in an actual existing metropolis and not in some artificially created world or virtual reality. As mentioned before, while both municipalities are geographically very close to each other, they differ significantly in terms of population, economy, and cultural background. El Alto is considered the heart of indigenous identity and resistance in Bolivia, while La Paz traditionally represents the political and economic elite. All this is reflected in the perception of the actual cityscape. While La Paz appears like a “normal” South American metropolis, El Alto looks more improvised and rather simple in structure. Walking through the city on the plateau, you notice that the infrastructure is limited to what is essential. Simple street kitchens and supplies for the population take priority here. Bars, better restaurants, and other sites of urban enjoyment are hard to find. The population seems too poor to indulge in entertainment venues. El Alto is also home to one of the largest markets in Bolivia, if not in all of South America and the largest open-air market in the world. Known as the Mercado 16 de Julio, it stretches over vast areas of the city. When we strolled through the market on a Thursday, we quickly realized that it cannot be explored in a day. It’s unbelievable how extensive the market is, and even after hours, there seemed to be no end in sight. Without a doubt, this is the largest marketplace I have ever walked through, and everything you can imagine is offered here. In addition to everyday products, the market is also known for selling unusual and bizarre items. There are stalls with spiritual and esoteric products, healing remedies, talismans, or various items for religious rituals. Part of the market, and likely all markets in Bolivia, is closely linked to Aymara culture and the belief in Pachamama (Mother Earth) and other spiritual beings. During market days, almost all street traffic in El Alto comes to a standstill, and during our first visit to El Alto, we also missed the Cholita-Libre event because it was impossible to reach the event location, but more on that later.

To slightly structure the entire madness of La Paz, I'll mention some facts, impressions, experiences, and events that left a lasting impression during my stay.

The cityscape in general can be described as quite unique. There are few undeveloped areas; in the valley and on the slopes, houses and huts squeeze into every tiny open space, right up to the last buildable area at the edge of the rugged cliffs and slopes that surround the city. It’s a stark contrast to planned cities like Brasília or Washington, D.C. The only order and constant in the cityscape is the never-ending chaos. It is loud, and there is always movement somewhere, like in a proverbial ant hill. With a height difference of nearly 900 meters between La Paz and El Alto, the descent into the valley leads to one of the most spectacular views on the South American continent. And above it all looms the snow-capped peak of Illimani, at 6,439 m the second-highest peak in Bolivia and a prominent landmark of the city.

Teleferico:

To explore the city, taking a ride on the Teleferico, the highest cable car in the world, is highly recommended. There are now a total of 9 lines connecting both cities, and for 3 Bolivianos (about 35 cents), you can enjoy spectacular views over the rooftops of both municipalities. The cable car system visibly helps to relieve the roads and the nerves of the residents; given the size of the city and the still catastrophic traffic, it undoubtedly meant that before the construction of the Teleferico, an appointment on the other side of the city would involve a day trip. In about an hour, you can travel in a sort of ring system to all essential neighborhoods using the cable car and get a wonderful impression from a bird’s eye view without having to plunge directly into the bustling hustle and bustle and without being stuck in traffic for hours.

By the way, to ease the traffic chaos, the city employs zebras. Although not real animals, these are people dressed in zebra costumes who help regulate traffic. Here, traffic lights are merely seen as decoration, and state authority is not fully respected; the zebras serve as a link between the state and the population, using red and green signs to manage the traffic. This surprisingly works well, and these animal helpers are taken seriously and respected. After all, who can defy a zebra that jumps onto the street with a wide grin, goofing around and pointing out the next green phase?

Cholitas- Wrestling:

As previously described, one of our first excursions to El Alto was to see the Cholitas. Combat sport and shows are nothing unusual in Latin America, and since I had already visited lucha libre fights in Mexico, I had a vague idea of what to expect here. Due to the chaos on one of the market days, we missed the first scheduled fight day and decided to return to the arena in El Alto another time. We booked the tour at one of the first hostels, and together with other foreigners, we made our way up to El Alto. For about 10 euros, you acquire an entrance ticket, including a snack, drink, and souvenir. An estimated 90% of the visitors here are tourists, and among the interested locals, they retreated to the back of the hall on the concrete steps of the grandstand while plastic chairs are reserved for foreigners right by the ring. I honestly didn’t like this two-class society; however, since the entire event likely primarily lives off the income of tourists, I can somewhat understand it from the operators’ perspective. It’s definitely spectacular to see the Cholitas take turns hitting each other in several matches, both individually and as a team. Clearly, it’s all a show, but the athleticism of the women is quite impressive, and with some of the moves displayed, I’m sure any ordinary person would break every bone in their body. Somewhat rustic at times, with punches, kicks, hair pulling, and mutual beer-spitting followed by crushing the can on the opponent's head, a wide repertoire of actions is presented here. This also has a serious background, as domestic violence against women in Bolivia is unfortunately widespread; the Cholitas have taken this as a reason to emancipate from violence, learn combat sports, and showcase it to the audience. The majority of the earnings also go to the fighters (so we were told), thus supporting women in their daily battle against violence. Definitely a fun and interesting event; if you’re in La Paz, you should experience it.

San Pedro Prison:

In the middle of the city at Plaza San Pedro lies the largest prison in the country, well shielded from the outside world with its 18-meter-high walls. However, San Pedro Prison has nothing in common with a conventional correctional facility. The prison has a nearly autonomous economic system. There are apartments and markets, restaurants, bars, and even small businesses that provide services to other inmates. The prisoners pay for their cells, and there is a clear hierarchy regarding the type of accommodation and social status within the prison walls. Wealthy inmates can buy or rent luxurious cells, while poorer prisoners have to live in miserable and overcrowded cells.

The exclusively male inmates in San Pedro often live with their wives and children. Early in the morning, the women take the children to school and then work somewhere in the city, selling food or souvenirs before returning to the prison with the children in the late afternoon. Since the first hostel was located in the immediate vicinity of San Pedro Prison, we could observe the colorful activities outside the prison gates daily; during rush hours, women and children sometimes lined up to return to their heavy men because the demand was simply too high.

There are reports that cocaine is produced and smuggled in significant quantities within the prison due to self-administration. Unusual methods are employed for this: sometimes transported by pigeons or packed in apples, which are then thrown onto the street and picked up and further transported by contacts. The residents are generally aware of this methodology; however, it tends to be accepted more or less tacitly. If someone mentions it, that person is automatically implicated in the gangs' schemes and part of the problem. So, it is better to keep quiet and avoid trouble. During a walking tour, we were advised not to pick anything up near the prison walls – smuggling seems to remain an ever-present issue. Originally intended for 300 inmates, there are now reportedly over 4,000. If you’re interested in how things look inside the prison walls, just type “San Pedro Prison” into YouTube and gain a visual impression of the conditions described in the facility.

The prison also became famous outside Bolivia through the book “Marching Powder,” which tells the true story of British drug smuggler Thomas McFadden and provides a deep and authentic insight into the daily life in San Pedro Prison, which is fundamentally different from other prisons.

McFadden was arrested in 1996 with 5 kilograms of cocaine at La Paz airport and incarcerated in San Pedro. Quickly integrated into the unusual prison system, the clever McFadden begins to make the best of his situation, offering unofficial tours for backpackers and other tourists into the prison's inner workings with the help of corrupt guards and other accomplices to tell the unique structure and stories of the inmates firsthand. McFadden gained notoriety through these tours, and the tourists helped him with the earnings to continually improve his life in prison. He rose to a position within the prison that provided him with protection and a relatively comfortable life, while violence and power struggles shaped daily life within the prison.

On one of these tours, he met the Australian Rusty Young, who was so fascinated by McFadden’s story that he wrote a book about it – Marching Powder. The book, published in 2003, became an international bestseller and made San Pedro Prison world-famous. The reports about prison life and the state of the Bolivian justice system shocked many readers, and after publication, the authorities tried to tighten their grip and curtail drug smuggling, which presumably only succeeded for a short time. At least the official tours into the prison are now strictly prohibited. There were reportedly some unpleasant incidents, and the government has finally put a stop to this. The last story I heard about the still unofficial tours was about 3 Australians who reportedly had to raise a significant amount of money at the beginning of the year to leave the prison unharmed. Surely such a tour would have been interesting for me as well, but under these circumstances it is certainly not feasible and just plain foolish and dangerous.

To this day, the book is not available in Spanish. Perhaps to avoid confronting the majority of the Bolivian population with the true conditions inside the prison walls.

Markets and Pachamama

I briefly touched on the significance of markets for the local population with the example of Mercado 16 de Julio. Entire neighborhoods are covered with stalls on certain days, and there are streets for sweets, hygiene products, clothing, or fruits. There is also bustling activity in La Paz. Even in major cities, there are very few actual supermarkets; all daily necessities are purchased in countless small kiosks or at the market. The business here in the country is traditionally firmly in women’s hands. Women are said to have a good business sense, whereas men are thought to take their earnings straight back to the next brewery to drink. Indeed, I noticed that during all my walks, almost exclusively women were behind the stalls. As a customer, for every item desired, you have your own market lady, who besides the goods also shares a bit of gossip and, depending on the length of the business relationship, offers a decent discount in the form of more goods. Thus, you stroll over the vast areas and shop with the respective “Caseritas” (the friendly term for market women) for potatoes, beets, or onions. And you should be careful not to avoid the respective caserita responsible for your desired product and go to another lady, because then, besides the good personal relationship, the special price and better quality of products are gone for good. In addition to traditional markets, there is also a witch market in La Paz, where you can find all sorts of tourist trinkets as well as very unusual products, such as dried llama fetuses, exotic herbs, talismans, amulets, and various ritual ingredients. Here as well, the goods are traditionally offered by Cholas or Cholitas (indigenous women) in their traditional clothing. The clothing of the Cholitas consists of a long skirt, up to 10 petticoats, a shoulder shawl, and the typical hat. The ladies also make for an interesting photo motif, but one should proceed with extreme caution when photographing the indigenous population or ask for permission beforehand. Many indigenous people believe that photographing them can steal their soul.

At the witch market, everything is closely linked to the deep connection of Bolivian society with traditional beliefs and nature. For the Western visitor, the market represents a bizarre attraction; for many locals, however, it is an essential part of daily life and spiritual practice. Here, the traditional knowledge of the Aymara culture is preserved, and Pachamama is revered. Pachamama, also known as Mother Earth, plays a central role in the indigenous culture of the Andes, both in Bolivia and Peru. She is considered the personification of the earth, goddess of fertility, nature, and life. Everything revolves around Pachamama here, and you are confronted with this theme almost daily. On the street corners in La Paz, you see shamans everywhere, called Yatiris, who facilitate personal contact with Pachamama, for personal contact is unfortunately not possible for the average citizen. The ritual goes as follows: You have a wish or need and would like to seek Pachamama’s assistance. So, you gather a few offerings and head to a Yatiri. The offerings (llama fetuses, coca leaves, candies, flowers, alcohol, or perfume) are arranged on a special tray and burned. Through the smoke of the burnt offerings, Pachamama sees the contact request and turns her attention to the person in question and their request. The offerings are meant to maintain the balance between man and nature and ensure her protection. Whether these rituals are generally successful, I cannot say, but it seems there’s something to it; especially in the city center of La Paz and near markets, you often see these ceremonies.

A central role in the colorful assortment of offerings play llama fetuses, which are especially needed when building houses. Before laying the foundation stone, ashes and a baby llama are included in the earth, thus securing the protection of the house by Pachamama.

There are also reports that when constructing larger houses and buildings, human sacrifices are resorted to in order to ensure protection. During the demolition of older structures in the cities, the remains of people are sometimes found in the foundations. Officially, this is no longer common practice today, and it is socially frowned upon, but several Bolivians have told me that this is still practiced. Rumors have it that homeless and alcoholic people are specifically targeted to honor them in one last “great night” before offering them. Also, on a free walking tour, human sacrifices were mentioned, but I could not find verified sources or evidence in my research.

In general, the cityscape regarding the demographic structure is heavily influenced by the indigenous population; about 40% of Bolivians identify as indigenous peoples, which is the largest share among all South American countries. However, over 80% of Bolivia's residents are Catholic. Since the colonial period, Catholicism has been deeply rooted in the country; the Spaniards successfully managed to evangelize a large part of the population.

At the center of La Paz stands the Basilica de San Francisco, built in the mid-16th century during the Spanish colonial period, which features one peculiarity: On the front facade is a representation of a naked woman, Pachamama. This figure was intended to encourage the indigenous population to practice the Catholic faith. The indigenous people, drawn to the Pachamama figure, entered the church, and were astonished. In the church, the Spaniards had placed mirrors. Since the indigenous people were unaware of mirrors, they were astonished by their own faces, and the Spaniards told them these were their souls. And if people came to church often enough and prayed to their God and their souls, their souls would be safe in the church and would ascend to heaven. Along with horrific depictions of hell shown to the indigenous people, which instilled great fear, they obediently attended church and prayed to the god of the conquerors. This is a vivid example of the creativity of the Spaniards in evangelizing the local population.

Apart from the execution of their traditional beliefs, the traditions and rituals of the indigenous population are omnipresent in the cityscape, be it at the markets, through the Cholitas, or the Yatiris. That’s what makes La Paz so unique and interesting for me; you feel like you've arrived in a different time, far removed from the modernity of European capitals. Notable in La Paz are also the many shoeshiners standing on every corner, often with their faces completely covered. Since the profession of shoeshiner is considered inferior and contemptible in Bolivian society, the men cover their faces, especially to avoid being recognized by acquaintances and relatives. It's a stark example of discrimination, which likely stems from the belief that during Inca times, the lowest job was to clean the feet of the Chaski (the messenger) after a long journey.

What else can I personally report about La Paz?!

Most of the time, I spent here with Nim, a wonderfully crazy Australian with whom I explored North Chile and Bolivia. After 3 days in a really awful hostel (much too small rooms, uncomfortable), we booked an Airbnb with two private rooms for a cheap price, and we also treated ourselves to some good rest after all the excitement of the last weeks and the daily adventures in the city. This was also necessary as you can feel the altitude at times and with the constant up and down through the streets of the city. In La Paz, I had a significant problem with the food for the first time on my trip and was out of commission for 3 days due to constant toilets visits from all body openings. I have no idea if it was already a food poisoning, but it definitely wasn’t enjoyable.

Of course, we also watched soccer, and a visit to the city's cemetery should not be missed during any stay in La Paz. While attending a match in the Copa Sudamericana: Always Ready – LDU Quito, we visited one of the highest football stadiums in the world (4,170 m above sea level), the atmosphere at the Cementerio General de La Paz was rather calm and respectful. Walking through one of the most significant burial sites of the country feels somewhat like being in a Wes Anderson film. All the artistic tombs, the magnificent mausoleums, and the morbid street art against the backdrop of the constructed slopes leave a quite surreal but somehow beautifully sad impression.

I could probably write for hours about everything I experienced or perceived in La Paz, but I instead recommend a personal visit to this crazy city – for me definitely one of the most exciting, if not the most exciting urban space I have ever moved in.

La Paz, the colorful city high up on the Altiplano as a melting pot of history, culture, and tradition: colorful chaotic, wild, contrasting, rough, rugged, windy, historical, hectic, exciting, authentic, diverse, breathtaking, and above all, UNIQUE!

Antwoord

Reisverslagen Bolivia