Navina im Dschungel

vakantio.de/navina-im-dschungel

Tag 154: Coffins next to bomb craters

പ്രസിദ്ധീകരിച്ചു: 04.03.2019

വാർത്താക്കുറിപ്പിലേക്ക് സബ്സ്ക്രൈബ് ചെയ്യുക

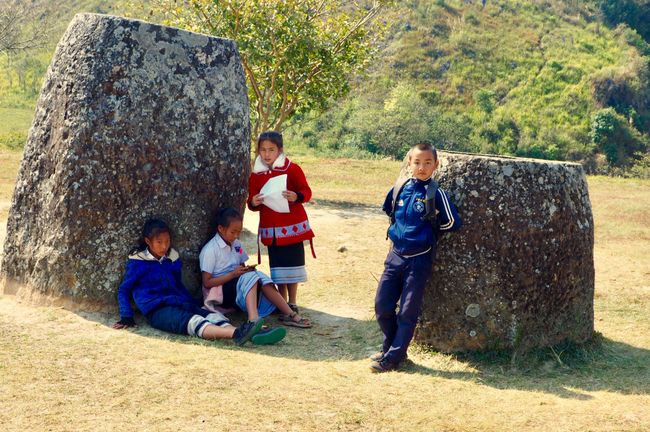

Our journey in Laos continued to Phonsavan, a city with a rich history. For almost 2000 years, there have been countless stone jars there, which were probably used as coffins back then. The people were placed inside with burial offerings, and years later, the bones were taken out. Today, only fat lizards and spiders live in the jars.

It's bizarre that there are bombs right next to these burial sites. These craters are only a fraction as old as the jars next to them. American bombs had exploded in this area during the Vietnam War, blowing up both soil and jars, as well as people. The craters are still clearly visible. Some of them already have small trees growing out of them. Even today, you're not allowed to leave the designated paths because there are still many undetonated bombs and mines in the ground.

The market in Phonsavan was different from other markets in Asia, because it was very organized. There was a fruit and vegetable section that was so diverse that we immediately bought ingredients for a salad to chop later on the balcony. The fish and meat section looked very gruesome, so I only glanced at it from a distance. In one part of the market, pig faces, bananas, and other snacks were being grilled. In another corner, you could buy pain-relieving and potency-enhancing powders, roots, hair, turtle shells, claws, and dried bundles, of which we didn't know if they were animal or plant parts.

Afterwards, Silke had soup for lunch. I still had the smell of pig faces in my nose.

A few days later, we continued towards Vang-Vieng on a minivan, driving along winding roads. Here, we could finally get sunburned again! With rented scooters, we, along with Robert and Bene, took a tour through the karst landscape.

The dust from the road turned the banana palm trees and our clothes red. Therefore, we started wearing face masks during scooter rides, just like the Asians.

Later, we took a small break at a lagoon, and Bene floated over the lake on a zip line with perfect form and gracefully plunged into the water. Robert's bet for this jump was a new bathroom.

On the way back, we had children waving at us and shouting "Kip." They wanted money from us. This happened to us quite often in Laos. Here, children learn early on that they can get money from tourists. It always feels bitter because children should not have to ask tourists for money. But their role here is to contribute to the family income in this way, even at the age of four. Unfortunately, we often saw children in Laos who served tourists in restaurants at 10 PM or carried heavy stones and wood on construction sites at the age of nine.

One morning, two pigs were slaughtered on the riverbank in front of our hotel. I stood on the balcony and heard loud squealing. Two men had tied the first pig's feet together and dipped it into the river upside down, as if they were dipping a piece of bread into sauce, washing off all the mud in which the pig had wallowed until that morning. Now the clean animal was ready to be slaughtered. The men waded back to the shore and laid the pig in the grass. The sun reflected in a blade and some spectators stood by the river to watch the spectacle. A foot kicked the pig's snout, causing it to squeal even louder. A hand struck the animal repeatedly with a stone, without aiming for a specific point. The blade swung up and down repeatedly. The men's rubber boots and forearms turned red, but the squealing simply did not stop. Eventually, I went back to the room. The pig surely didn't have a quick death, although the men could have made it possible. The only problem was: they didn't care. That's why the pig was still alive when its head was scrubbed under water in the river and it was still alive when the stone hit its snout and the blade had already swung up and down into its body five times. This experience, and the brutality with which it was carried out, was surely one of the worst of the trip, but it was part of it.

Our last stop in Laos was Vientiane, the capital city. A river wound its way past the city, and the cars driving on the other side of the river were on Thai soil. What I only realized much later is that Laotians and Thais can communicate because the two languages are very similar. In this cross-border friendship, Thailand is always the country where the economy is running, where tourists travel, and where there are hospitals. In Laos, as it seemed to me, Thailand is looked up to. "Made in Thailand" is considered a mark of quality.

What will stay in my memory about Laos is the great asymmetry between the rich and the poor. In Vientiane, the streets were tidy, there was a mango store, and the magnificent Presidential Palace could easily accommodate 200 people. It is unreal that it is the same country in which people live in woven huts in the mountains. In these villages, fires are used for cooking, classes are held in crooked huts, and pigs roam freely while the dust envelops the residents' clothes and the house walls in a monochrome color. Laos is above all an asymmetrical country that often appears harsh beyond the Hmong villages. In contrast to all the other neighboring countries we have visited, the people here often have a suspicious expression on their faces. Children, in particular, are treated more roughly than elsewhere. Perhaps this is due to the recent war and the horrors that people have experienced here; after all, Laos is the most bombed country in the world. The harsher mentality may also be due to the form of government. In any case, we were looking forward to the warmth in Thailand.

വാർത്താക്കുറിപ്പിലേക്ക് സബ്സ്ക്രൈബ് ചെയ്യുക

ഉത്തരം

യാത്രാ റിപ്പോർട്ടുകൾ ലാവോസ്