Dreams and Ideals

Diterbitake: 24.07.2022

Langganan Newsletter

It is about approaching the ideal. What is already difficult in everyday life turns out to be an almost impossible undertaking when modeling statues. The point of absolute perfection cannot be reached.

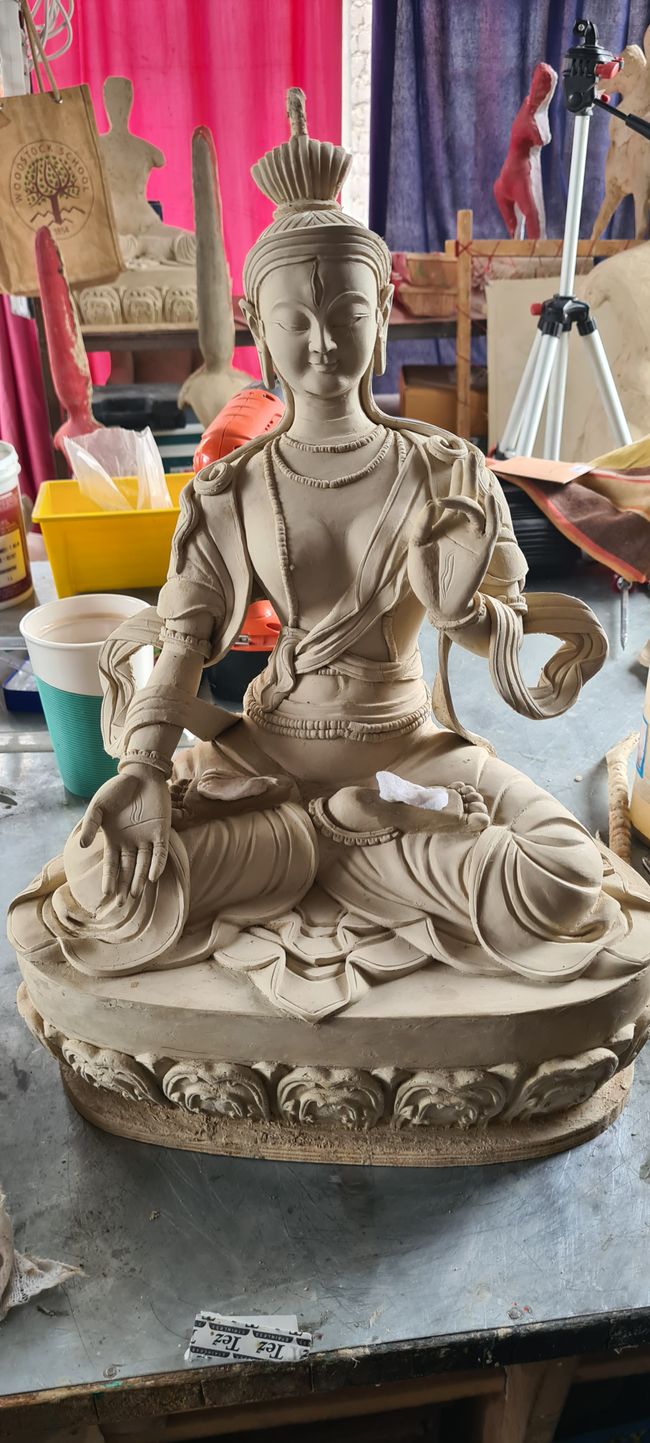

In Chhemet Rigzin's workshop, this becomes clear to me right away. Just remembering all 32 characteristics of a Buddha is already something. Putting them artistically on display is something else entirely. However, I am now learning the methods to at least approximate the perfect image of Buddha to the best of my limited abilities.

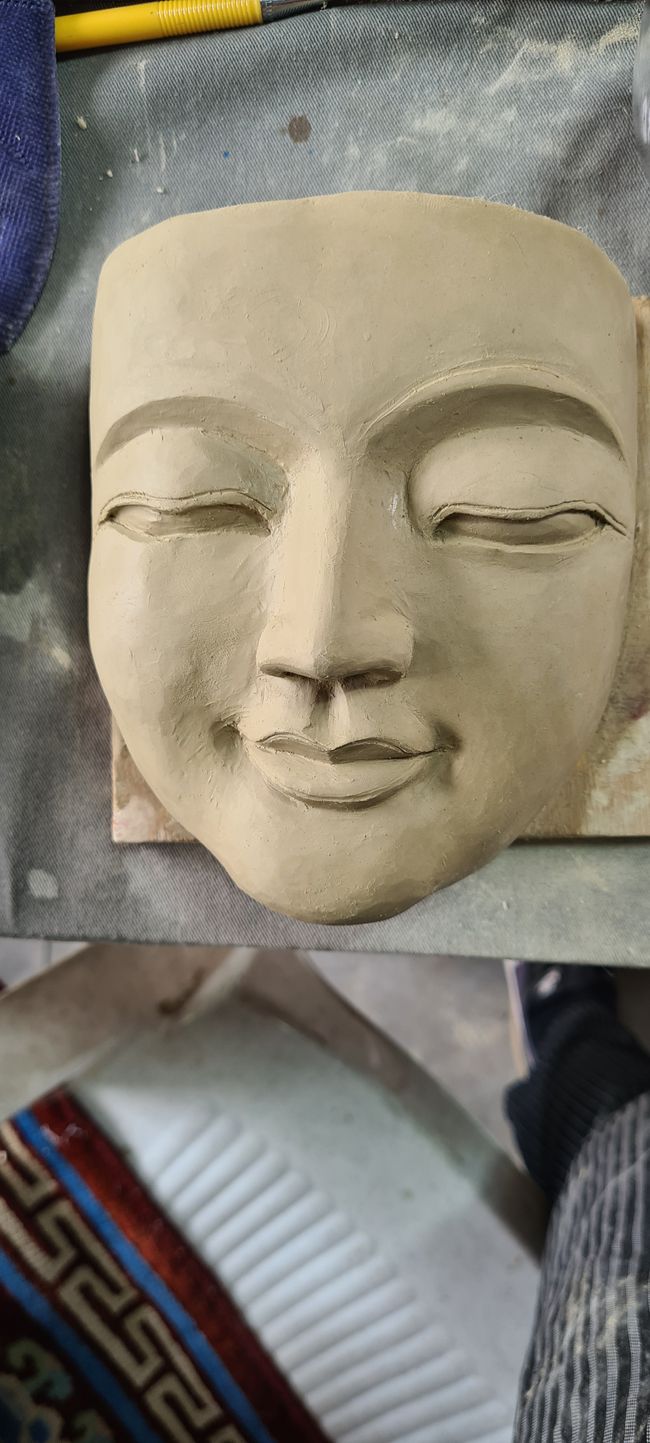

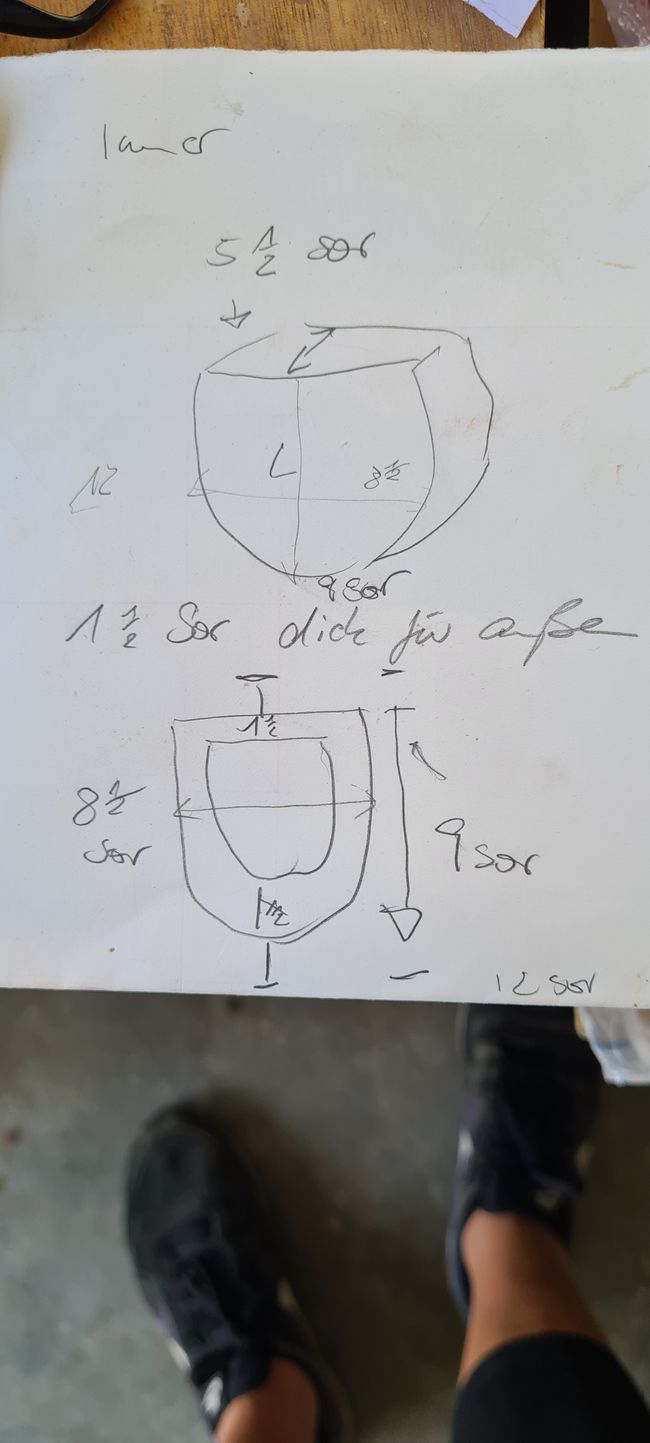

I have already mentioned the relative measurements. Now Chhemet shows me a method of initially using these measurements in drawings. It involves creating a kind of grid for the specific points of the Buddha's face, which is very helpful for the subsequent drawing. And the more of these faces I draw, the more familiar the shapes in the Buddha's face become to me.

Baking is easier

Chhemet's son Stanzin is always with us too. He is also learning from his father. This is very helpful because as a student, he has a much better understanding of my sometimes very clumsy attempts - and he also has more praise for me than Chhemet does. This is necessary because sometimes I really feel like a complete amateur. My first Buddha face made of clay is still far from the symmetrical ideal, but eventually the clay becomes so dry that I give up my desperate attempts at improvement.

Meanwhile, I have also moved. Angmo's hotel is fully booked on some days, so I accept her offer to stay at Thok Thok Homestay. It is not only located right next to Angmo's family home, but is also run by her relatives. This family welcomes me very warmly and anticipates my every need. Meanwhile, Angmo tirelessly takes me back and forth, bringing me to Chhemet's workshop every morning and picking me up later.

A new attempt and a hole in my pants

'Another attempt with clay?' Chhemet asks me one morning. And he receives only a horrified groan from me when he suggests a significantly smaller measurement. But - who would have thought - either this smaller measurement suits me better, or the constant drawing of the Buddha's face is starting to bear fruit. Or maybe both. In any case, the second face is already turning out a bit better.

And something else is going to be successful on this day. I have brought a recipe for German bread from Germany, and Chhemet is excited to bake it in his mini-oven. So we go shopping with Stanzin. It's not that easy. Finally, we manage to find the seeds of anise, fennel, coriander, and cumin with some translation difficulties. In this way, I am learning all the expressions for the bread ingredients in English and even some in Ladakhi. In the end, the effort pays off. Chhemet's family is delighted with the bread, and my other two families are also pleased with their share.

However, I lose a pair of pants when I try to bring the freshly baked bread slices to Angmo's house. For the first time, nobody is home there. And the dogs guarding the family home are not happy to see me. Barking and biting, five of them chase after me along the dusty path, fortunately leaving only a hole in my leggings and not in my skin. By the way, this happens in broad daylight and not at night or anything like that. A lesson for me. I won't take this path alone anymore.

Sausage-like fingers to measure

The next day, Chhemet surprises me with the task of sculpting the first Buddha hands and suggests visiting his family's house in Tia. We agree to take this little trip on the last few days before my departure to Germany to visit various monasteries where both Chhemet himself and his father have built statues. I have already seen one of them under construction when I visited with Amira Tingmosgang a few years ago.

But first, I receive a hand drawing from Chhemet with measurements for the palm and fingers. Based on these measurements, the first step is to model the Buddha's fingers. For example, I learn that the thumb must reach to the end of the first joint of the index finger, and that the ring finger must reach half the length of the middle finger's nail. The circumference and length of the fingers are precisely specified - of course, in relation to Sor, Nas, and Kangspa measurements.

The first hands

So I work on the fingers all day long, and after a while, they start to remind me of little sausages. I still can't imagine how these sausages will become Buddha hands. It only starts to make sense to me when Stanzin presses his fingers finished the day before into the clay according to his father's instructions, adjusts them, and adds more clay for the slightly higher positioned thumb. The hands that are created in this way look really great. However, mine, well, let's leave that aside.

In between, Chhemet tells me about his dream. 'I am still relatively young,' says the 50-year-old. But he knows that time is running out. And that the precious knowledge he received from his father Nawang Tsering, who in turn received it from an old master named Tsewang Rigzin, could be lost. That's why Chhemet is currently building a new studio in front of his house, to create more space for passing on the precious knowledge of statue making. His dream is to establish an art center where Western students can also learn the methods to approach the ideal of Buddha.

The dream of LHAIZO

He has already come up with a name for the art center. The title 'LHAIZO' stands for Ladakh Himalayan Art International Zone, but also means 'Lha' for Buddha or Bodhisattva, 'I' for the genitive, and 'Zo' for art, so it also means Buddha's art. 'Maybe we can even organize large exhibitions of my sculptures and the students' statues,' the master muses, already envisioning how the partially painted and partially unpainted artworks would be presented. But just like my skills, the entire project is still in its early stages. A lot of energy and, of course, finances are needed for the child to learn how to walk.

Meanwhile, time is also running out for me. As we set off for Chhemet's hometown, I only have three more days left in my second home, which evokes mixed feelings in me. Of course, I'm looking forward to seeing my loved ones at home and - admittedly - to the comforts of Germany. But another part of me sheds hot tears at the thought of having to leave this wonderful country.

Hot tears and heartfelt wishes

Right now, when the apricots are ripe and August, one of the most beautiful months here, is just around the corner, I have to turn my back on the Chakrasamvara Drubchö starting in Lamayuru and the teachings of the Dalai Lama planned for August. I will now miss all of that. And I will also not be able to see my refuge teacher Lama Jampa after all.

That's why I leave heartfelt wishes for a reunion and the opportunity to continue my apprenticeship as quickly as possible in Tia and Tingmosgang, both in the old and new Gompas. In Tingmosgang, there is a very old spontaneous Chenrezig statue. When I mentally express my wishes in front of it, I strongly feel like it somehow works. We will see...

Tomorrow, the plane will take me home. But the adventure of life continues. That's why this may not be the last report about my journey to new experiences.

Langganan Newsletter

Wangsulan