The city that has given the most to the world

उजवाडाक आयलां: 15.11.2018

खबरांपत्राची सदस्यताय घेयात

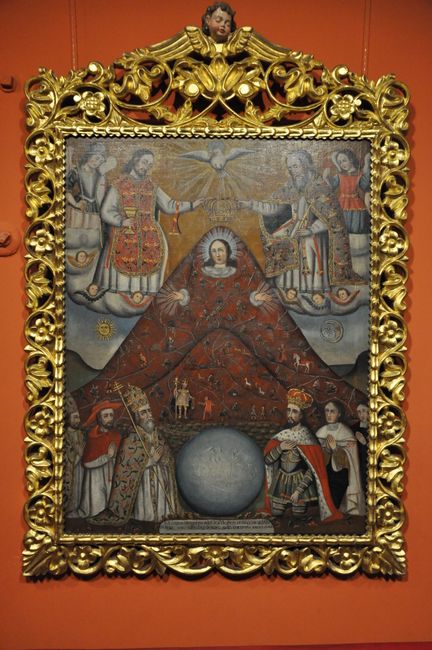

That's how it's generally known in Potosí. But at what price? Potosí is overshadowed by Cerro Rico (rich mountain), a spectacular cone-shaped mountain. The first silver discovery in the 16th century was supposed to seal the fate of the city. The Spanish colonial rulers hollowed out the mountain bit by bit, at the cost of around 8 million Indians who have died in the mines to this day. For centuries, Potosí was the richest city in the world. Several tens of thousands of tons of silver were extracted and initially attributed to the Spanish crown before this silver spread throughout the Spanish empire. Silver coins were produced and minted onsite in Potosí.

#quiteinteresting1: When we flew to Peru in July, we took the Spanish airline Plus Ultra and were already wondering about the name. Actually, the name comes from the Spanish coat of arms, whose columns of Hercules marked the end of the known world at Gibraltar. The Spaniards, including this airline, go beyond this end (plus ultra) into the New World. We didn't know that, at least not until now.

#quiteinteresting2: Why is Argentina (argentum=Silver) called that even though there is hardly any silver there? The Argentine Rio de la Plata (Silver River) was an important transport route for Potosí silver to or via Argentina. Aha! Haha.

#quiteinteresting3: So where does the $ symbol actually come from? The coins minted in Potosí were marked with the abbreviation PTSI. The letters were superimposed. Since the value of the dollar was dependent on Spanish silver until the presidency of Nixon, the letters P and T were simply omitted, leaving only the S and the I=$. The symbol for money worldwide. This is at least one of the common theories.

Even today, 16,000 mine workers are active in the mountain, although less silver is being mined now, but instead tin, zinc, and lead, although the yield is rather moderate. Cerro Rico is now more of a Cerro Pobre, so exploited it is. The working conditions are still at the standards of the 19th century, only with a flashlight. Children start working there at the age of 13, sometimes even earlier. Ideally, young people are only allowed to do such work from the age of 18, which is partly enforced. The consequence of this is that there is still child labor there, but these children work at night. 700-800. More in the movie 'El minero del Diablo' (2005).

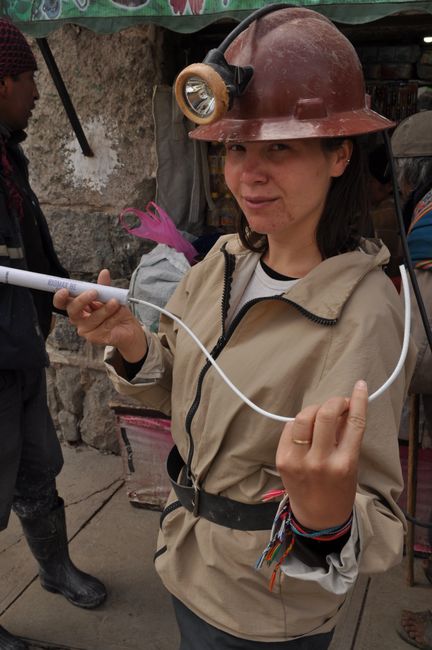

We also visited the mines. One and a half hours in dusty darkness, bent over in low tunnels and narrow shafts. There is hardly any support for the shafts. This is particularly exciting when the workers ignite a load of dynamite. The whole mountain trembles and it is not uncommon for a tunnel to collapse. 13 explosions in a row, not only the walls tremble, but also the people. But very exciting! Miners are always brought a gift. Either coca leaves (which make the 14-hour shift bearable) and pure alcohol (for Pachamama and the devil) or dynamite. It's about to go boom. Boom. Willem was very excited that he was allowed to buy explosives for once.

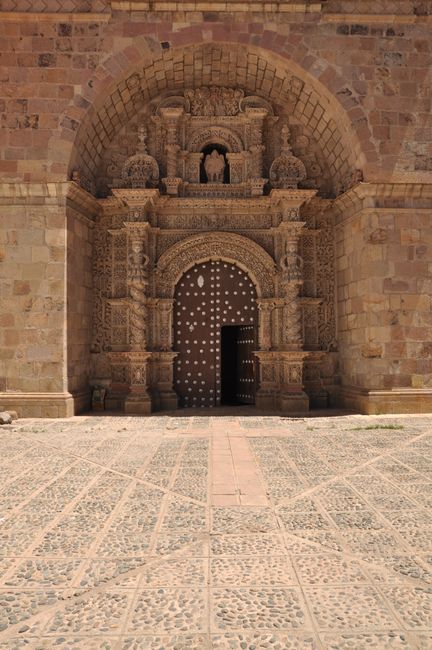

In addition, Willem had found another treat in Potosí. In the cathedral, there is a FUNCTIONING (imagine that) organ that has just been renovated! And indeed, WE were allowed to play music for a good hour during visiting hours, something we both miss very much. So it was all the more beautiful that it was possible on this Walcker organ (approx. 1930, German-made).

खबरांपत्राची सदस्यताय घेयात

जाप

प्रवास अहवाल बोलिव्हिया