Round trip through the southern part of Bolivia

Foillsichte: 11.12.2017

Subscribe to Newsletter

My short stopover in La Paz was history and now the Bolivia tour began. Uyuni with its famous salt flats was planned as the first stop. Since the city, which has just under 20,000 inhabitants, has little to offer except tour operators, I wanted to spend as little time there as possible. I took the night bus from La Paz at 8 p.m. and arrived in Uyuni 11 hours later completely exhausted. But my pre-booked tour didn't start until around eleven, so I spent the time until then in a café at the bus station. There I also met the first fellow travelers who had booked with the same tour operator. Bastiaan from Holland and Tom from England. We got along quite well from the beginning and decided to ask if we could ride together in a car.

Several hours later, it finally started at Perla de Bolivia. After a brief introduction, where our guide emphasized about twenty times that we should please bring enough money to buy something along the way, the group of 17 travelers, one guide and three drivers set off with three cars. Only llama farmers, miners, and the Bolivian military have settled in the barren, up to 6000-meter-high countryside, which we want to cross over the next few days.

The first stop was the Cementerio de Trenes (Train Cemetery) just outside the city. The first railway line in Bolivia was built in 1872 and served to transport raw materials such as sodium nitrate, salts, or metals such as copper, silver, and gold to the port cities on the Pacific. At the end of the 19th century, the line reached Uyuni and a railway engine was built, making Uyuni an important hub. When the local industry collapsed in 1940, many mines were abandoned by their operators and therefore most locomotives were no longer needed and simply left behind. Nowadays, the local train cemetery is the largest in the world and serves as a photo opportunity for many travelers on their way to the largest salt flat in the world, the Salar de Uyuni.

We continued to a small village where we were shown how salt was processed and where we were then invited to buy something at one of the seemingly hundred stands that all had the same offer. Out of principle, I decided against it, and so we continued and reached the salt flats.

The Salar de Uyuni is a more than 10,000 square kilometer salt pan, over twelve times the size of Berlin. It formed over 10,000 years ago when the Paleo Lake Tauce dried up. It is located at an altitude of approximately 3600 meters and is up to 100 meters deep in certain areas. In the meantime, the dried-up lake is mainly used for salt extraction and tourism. The amount of salt in the Salar de Uyuni is estimated at about ten billion tons. Around 25,000 tons are mined annually and transported to cities.

It also contains a huge deposit of lithium.

During the rainy season between early December and June, the lake is covered with a layer of water and partly impassable. During this time, the Salar de Uyuni becomes the largest mirror in the world.

After we had lunch in the middle of the desert, it was time for the photo session. Because of the seemingly endless expanse, you can take wonderful perspective photos. However, since I am not a particularly talented photographer, others had to deal with the techniques.

Next, we drove with the jeeps to the center of the salt flats to Isla Incahuasi, an elevation known for its partially over 1200-year-old columnar cacti. There we hiked up and had a wonderful view of the salt flats from above with a cold beer in hand.

We spent the night in accommodation at the edge of the salt flats, where the floor was completely made of salt. I had the only triple room together with Bastiaan and Tom. There were only double rooms available otherwise. Besides two other solo travelers, there were only couples traveling with us as well.

The next day, after breakfast, we set off to visit some lagoons in the Eduardo Abaroa Andean Fauna National Park, named after a war hero from the nitrate war. The first two lagoons were unspectacular except for the many flamingos and smelled pretty bad, but the third lagoon, the Laguna Colorada, was truly impressive. It gets its name because of its striking red color, and countless flamingos also inhabit it. By now, we were at an altitude of 4300 meters, and some people could feel it quite a bit. I had had slight headaches for a few days, but hardly any restrictions. However, you quickly notice the altitude when you move around a bit.

Later, we passed some geysers and mud holes, whose smell of rotten eggs reveals their sulfur content, and by now we were at almost 5000 meters above sea level. The wind was cold, and the temperatures almost reached freezing. In the evening, we slept in a very spartan hostel in six-bed rooms, but we were lucky that there were hot springs right next to the hostel where we could bathe in hot water.

On the last day of my three-day journey through the fauna of southwestern Bolivia, we set off for Laguna Verde in the morning. On the way there, we passed the Salvador Dali Desert. Shaded from light to dark brown, the rocks are scattered on a hill, as if God had dropped a few pebbles out of his pocket. In fact, it seems as if you are darting through a painting by the Spanish artist. A surreal image. Only the melted clocks are missing.

Arriving at Laguna Verde, the first little disappointment. Unfortunately, the lagoon was not green as expected, but a normal lake at the foot of the Licancabur volcano. The volcano, at almost 6000 meters, is the highest inactive volcano in the Cordillera Occidental, which is a section of the Andes and also forms the natural border with Chile. In the crater, there is one of the highest lakes in the world, and despite temperatures of -30 degrees Celsius, a variety of organisms thrive here. This is also the reason why NASA and the SETI Institute have undertaken some expeditions here to understand the development of life in its earliest stages through insights into the adaptation of organisms to external conditions.

Afterwards, we headed back to Uyuni and only stopped once on the way at a llama herd grazing at a hidden lagoon in the middle of nature.

The journey was exhausting and long, but around five o'clock we arrived back in Uyuni. Finally back in civilization, I spent the two and a half hours until my bus to Potosi left in a restaurant with some of the others, who were all going back to La Paz.

The following four-hour journey was cold and the bus smelled musty. But at a fare of less than five euros, I can live with that. When I arrived in Potosi, it was already past eleven o'clock in the evening, and I shared a taxi with a Swedish couple to my hostel. Completely exhausted, I then fell asleep immediately after a day full of driving.

The next day, I wanted to explore Potosi and set off on a discovery tour with Becky from my hostel. However, there wasn't much to see here, and it was terribly cold as well. That's why I decided to take the bus to Sucre the next day.

Potosi is located at an altitude of 4000 meters, has a population of almost 175,000, and is located at the foot of the Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain), whose silver wealth made Potosi one of the largest cities in the world in the early 17th century and from whose silver and tin deposits the city still depends on today.

The city is best known for the tours of the local silver mines. They are not particularly interesting to me, so I decided against them. Becky wanted to visit a monastery nearby, and since I didn't have anything special planned anyway, I accompanied her. There, we enjoyed a one-hour private tour for only 2.50 euros. Unfortunately, the tour was in Spanish, and since neither of us spoke much Spanish, we didn't get much information. We were guided through the monastery, were allowed onto the roof, from where we had a great view of the city, and into the catacombs, where the dead are laid out in a ceremonial manner. I didn't quite understand it, but it was definitely quite creepy.

The next day, I took the bus to Sucre in the afternoon, a three-hour journey, and this time I got on an extremely hot bus. The hint from an Australian in Sao Paulo that in Bolivia, you almost always either get extremely hot or extremely cold buses, turned out to be true. In Sucre, I checked into my hostel, and for nine euros per night, I even got a private room.

Sucre is the capital and is located in southern Bolivia. In terms of population, Sucre is only the sixth largest city in Bolivia, but for me, it is by far the most beautiful. The old town of Sucre with its white buildings is considered one of the best-preserved examples of a colonial city in South America and is laid out in a typical grid pattern. In 1991, the old town was recognized as an ensemble by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. UNESCO justified this with the large number of well-preserved 18th-century houses and the fact that later buildings were also constructed with courtyards and in the style of Spanish colonial architecture.

The old town in particular invites you to take a stroll, and the Plaza de 25 Mayo, the main square of Sucre with the beautiful Cathedral Metropolitana de Sucre, is truly stunning.

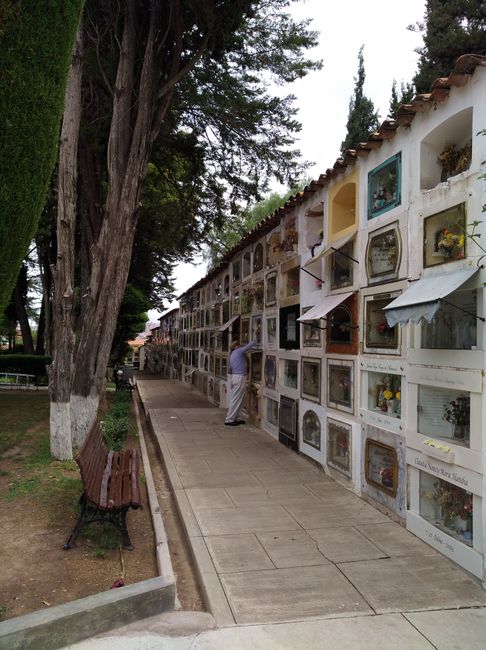

In Sucre, I met Becky from Potosi again, now accompanied by her boyfriend, and together we went to Sucre's cemetery, which was supposed to be one of the sights. Unlike the cemetery in Buenos Aires, this one rather resembles a traditional cemetery, but it is worth seeing due to the beautiful buildings and perfectly maintained garden landscape.

We spent the rest of the day in various cafés and restaurants, playing cards. The day went by quite quickly, as in the evening, the next night bus was on the agenda. We are going back to La Paz. A smooth 13 hours back to La Paz.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Freagairt (1)

Heiko

Hallo Emil, deine Reise durch Bolivien verfolge ich mit Interesse und entsprecheder Literatur sowie goole. Dabei sind deine persönlichen Erfahrungen das Beste um sich ein gutes Bild vom Land zu machen. Alles Gute und viel Freude bei den weiteren Touren, Opa Heiko