Of big question marks, tornadoes, and an exhibition about DPs in cardboard boxes

Argitaratu: 01.08.2023

Harpidetu Buletinera

Today, not a follow-up but a preface - a 'foreword,' so to speak:

Some texts come easily to me. The many encounters, the work in the archives, being on the road. I have an idea, a beginning for a text, I make a few notes, and I quickly write it down on my phone; it doesn't take long and the text is finished - or at least a draft.

But I have thought long and hard about the following contribution; I have rewritten it several times, asked some friends if they could read it; I have postponed publishing it again and again because I am (still not) really comfortable with it. What I mean to say is: this contribution was more difficult for me.

Why? Many things are working inside me. With regards to what I am looking at here, what I read and hear, the many conversations, personal encounters, and at the same time the scientific texts I read about it; about the context, the Ukrainian diaspora, the individuals I am studying. Texts that I am reading again, perhaps differently than before?

In many parts, it is also very confusing. A few days ago, there was a tornado warning here. I immediately had images of huge twisters and devastated landscapes in my mind. Fortunately, nothing happened here - but the storm was felt and it caused a lot of chaos - maybe even symbolically in my mind.

Therefore, the following text is a published draft that may be revised, edited, changed, rearranged, or maybe even deleted in the near future. That somehow sounds dramatic. :D But it rather shows: work in progress, something is being worked on, in the process. And then I thought that somehow it fits well with the current situation and should be like this. So, welcome to the historical chaos.

Sometimes I wonder what it would be like if someone unfamiliar came around the corner and asked about the history of my parents or grandparents, interested in documents, personal records, photos; wanting to talk to me.

I can imagine that it would be strange.

Would I talk to the person, take the time? Probably yes. But even if I don't actually know as much as I think I should? That could also be uncomfortable. And maybe something would come out of it that I wouldn't want to know myself, something that may have been kept silent for a long time.

I have the impression that this crossed the minds of many people when they received a request from me in recent years. Especially for some, my questions may be unusual. With some, I am certain that they caused discomfort, with others, I suspect.

Most people - at least from what I perceive - only ask about the (own) stories and lives of their ancestors when they are already deceased. Then it is often too late and, if at all, very challenging work. Often, there is no real starting point for something like this because where should one actually begin?

And then time continues to pass. The inquiring person becomes older and maybe at some point, the grandchildren will ask, and then the inquiring begins again from scratch.

For some, these old stories don't matter, while others find them very fascinating as long as they don't have to do the research themselves. This often has little to do with convenience; it is more about the fact that some things are hard to find, hard to understand, especially when it comes to personal, individual stories.

Family archives can be a real treasure, but if something is passed down, it means that there was already at least one person in the family who was interested and started collecting. But even then, being able to look into it as a stranger requires trust.

Another possibility is community archives, non-governmental archives of individual groups. Working with them also requires trust; especially a leap of trust from the researching person. This is not self-evident. Just as it is not self-evident that descendants or survivors share their story/stories with me. The question often also includes what I am going to do with it. How will I interpret the things? How will I present them and thus also the people connected to them later on? Do I have any hidden agenda? Am I being paid by someone for my work? Sometimes the skepticism is strong. But more often, especially in recent years, I have sensed it in subtler tones.

The Ukrainian diaspora, especially in Canada, is often - from their point of view, almost always - accused of anti-Semitism, the accusation that they were all National Socialists, ultra-nationalists, Nazi collaborators. And if not all, then the vast majority. The same often applies to the Lithuanian, Latvian, and Estonian diaspora. Especially from the 1980s onwards, international trials against actual and alleged collaborators with the National Socialists intensified this impression. In recent years - now actually decades - Russian propaganda has fueled this image even more.

Regarding Ukraine: How to deal with Stepan Bandera - the particularly controversial, anti-Semitic, ultranationalist leader - and his followers is still often debated and remains a constant topic; in Ukraine, in the diaspora, abroad; in Poland and Israel. For some, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) is a mass murder gang that cooperated with the German Nazis, murdered Jews and Poles; for others, its members were (also) freedom fighters for an independent Ukraine. Still, others argue that it is important not to see everything in black and white, but to consider the many shades of gray in between. Difficult, indeed.

The urgency of these issues has increased since the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. There are topics - historical as well as current - that seem even more difficult to discuss for many than they already were.

Therefore, in my research, I find myself in very uncertain terrain, dealing with very delicate, sensitive topics. And for many older people, the history of the 20th century seems to be repeating itself, at least in parts. This is not without challenges.

I also occasionally feel the difficulty of speaking when working in the archive in Toronto. I also have to deal with problematic sources, self-testimonies, and narratives that do not align with the prevailing narratives about the Second World War in Eastern Europe, to put it mildly: following different narratives. Dealing with that is not easy, and at this point, it should only be mentioned that I am grappling with some current and future tasks. In the midst of this, the language aspect is a secondary challenge.

Kalyna was an enormous help in the search at the Ukrainian Canadian Documentation and Research Center (UCDRC). She herself is the child of two DPs. She was born in Innsbruck shortly after the Second World War. When she retired, she was looking for a new task. She had already been involved as a tour guide and volunteer in museums in Toronto for many years. At the same time, she had memoirs from her parents that she wanted to donate to an archive. 'It's better off there,' she said, which is how she came across the UCDRC. She did not know about it before, even though she grew up in the Ukrainian diaspora here in Toronto.

Her parents didn't talk much about the Nazi era, the DP era; the story really began, as she said, after emigration to Canada. Looking back, however, she also said that she never really asked any questions. The questions only came to her when her parents were already dead and she was much older. She only knows fragments of what her parents experienced. There was a significant gap in her family history that she remembered. Her mother was in prison, ended up on a transport. The written memoir ends there. The only thing Kalyna remembers well is the story of old rags and pieces of fabric that women used when they had their period in prison. Her mother told her that almost incidentally when Kalyna was a teenager. Kalyna remembers how puzzled she was by this story. That's really all she knows about her mother's imprisonment. Where it was, for how long? Unknown.

Kalyna took on a project at the UCDRC as a volunteer. A project on female prisoners from Ukraine in the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Everything she knows about concentration camps, the Nazi era, and what happened afterwards, she knows mainly from this and the research she did for the project, she tells me.

She created a database and tried to gather as many names and stories as possible. Like me, she mainly worked on it during the Covid lockdowns. Now she is slowly approaching the end of the project. A book is supposed to be produced, an online event has already taken place, and the interviews are to be made available online.

Kalyna's work was a very important foundation for my research here, enabling me to continue researching and navigating the local territory. She is also familiar with the materials on concentration camps and the local archive. That helps, and she prepared some things for me, searched her records for things that might be of interest to me.

Since she started working on the project - once a week as a volunteer - more things have been digitized. This allows me to work through them more quickly from my temporary home in Toronto - I am not dependent on opening hours.

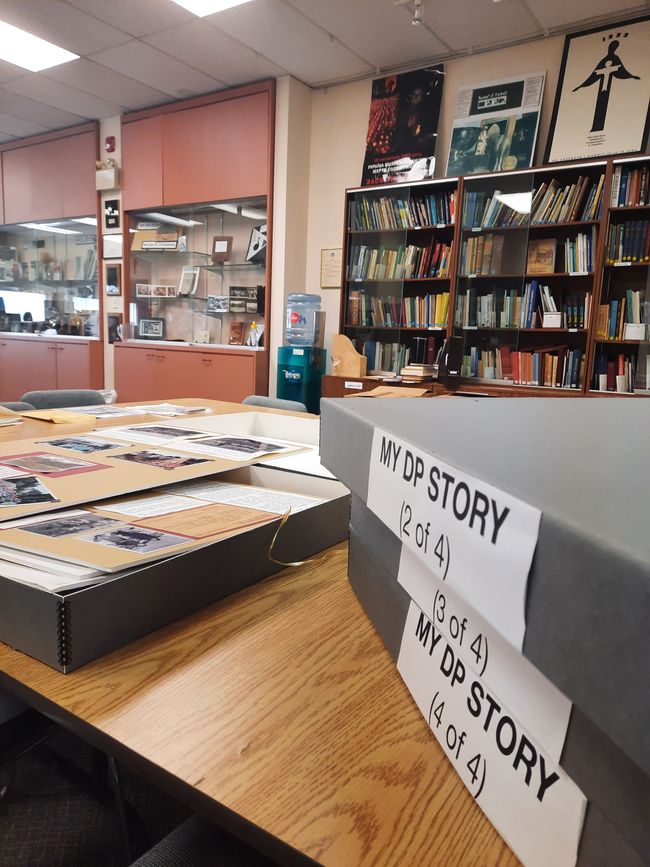

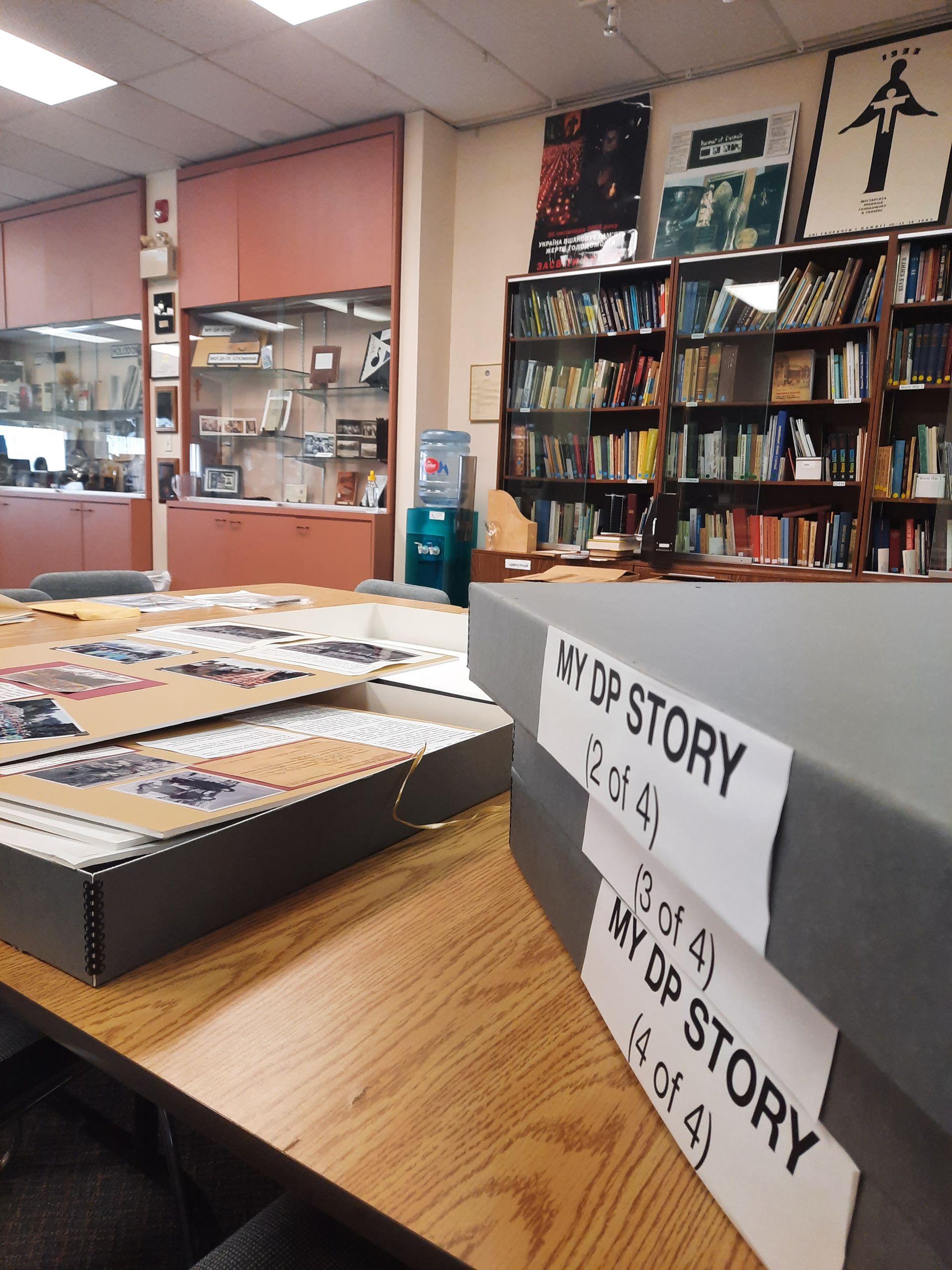

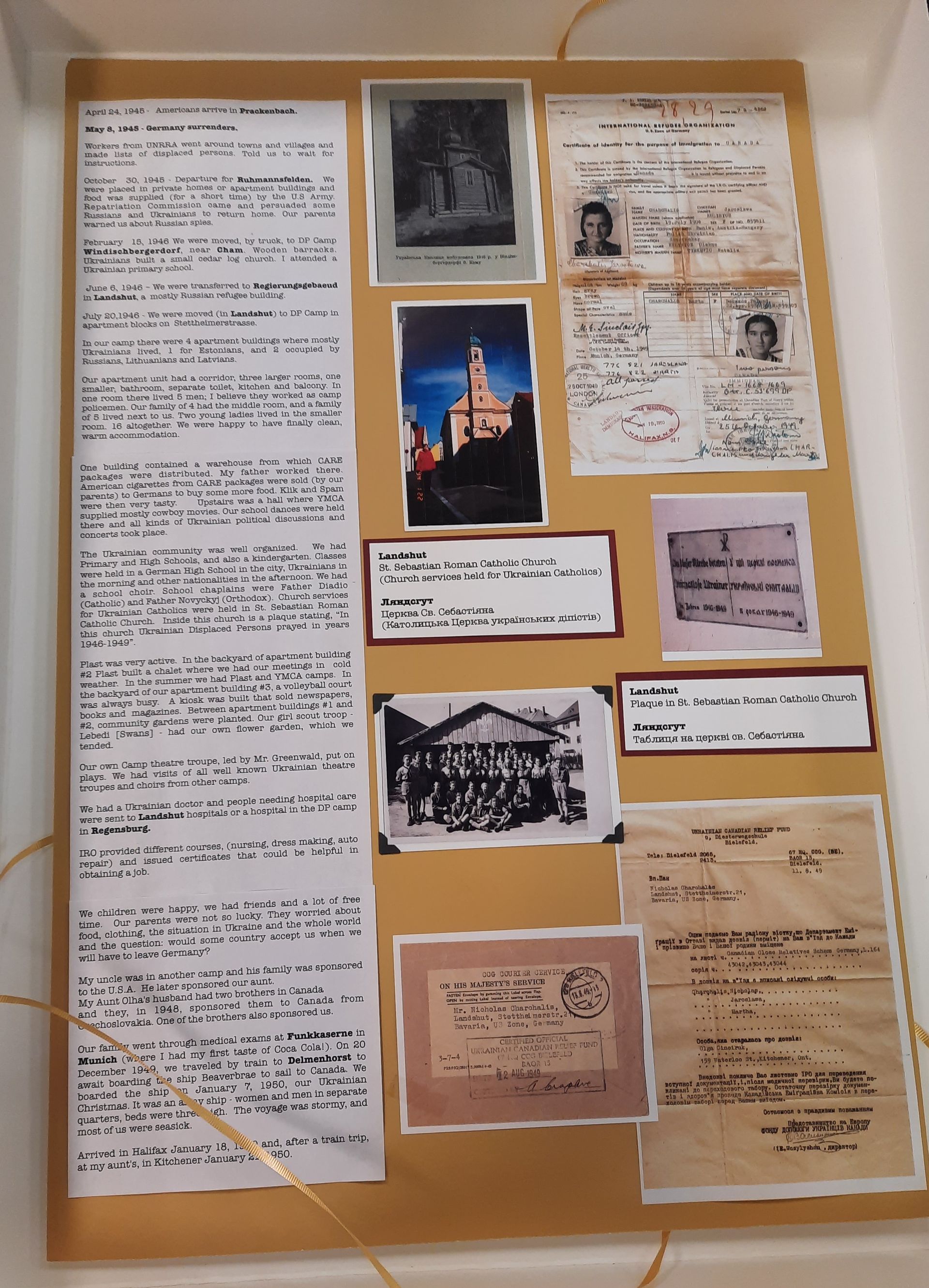

The Exhibition: My DP Story - Meine DP-Geschichte

Recently, there was an exhibition at the UCDRC about DPs, only a small part of it remains. The rest has been packed in four large boxes for a few weeks now, and I was allowed to unpack them again.

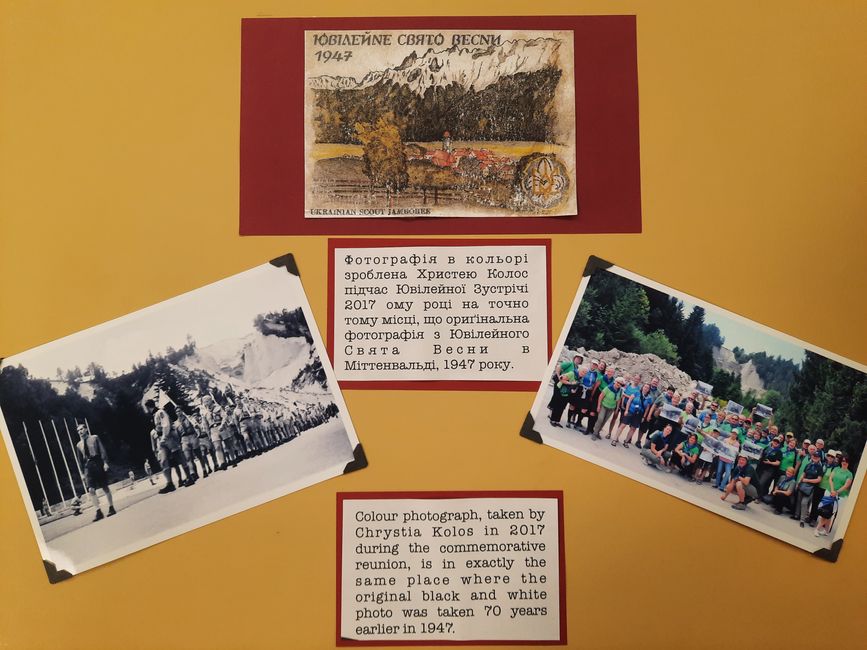

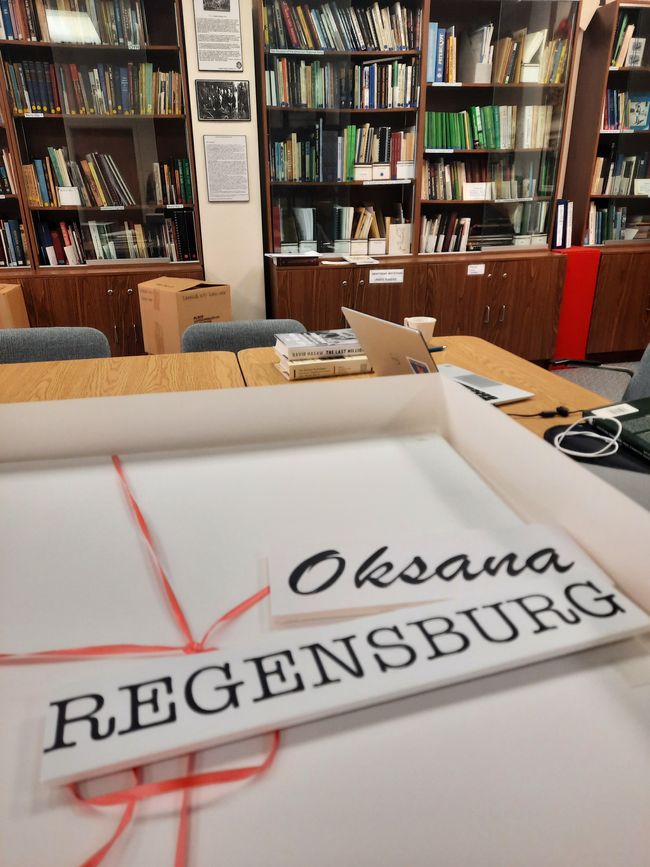

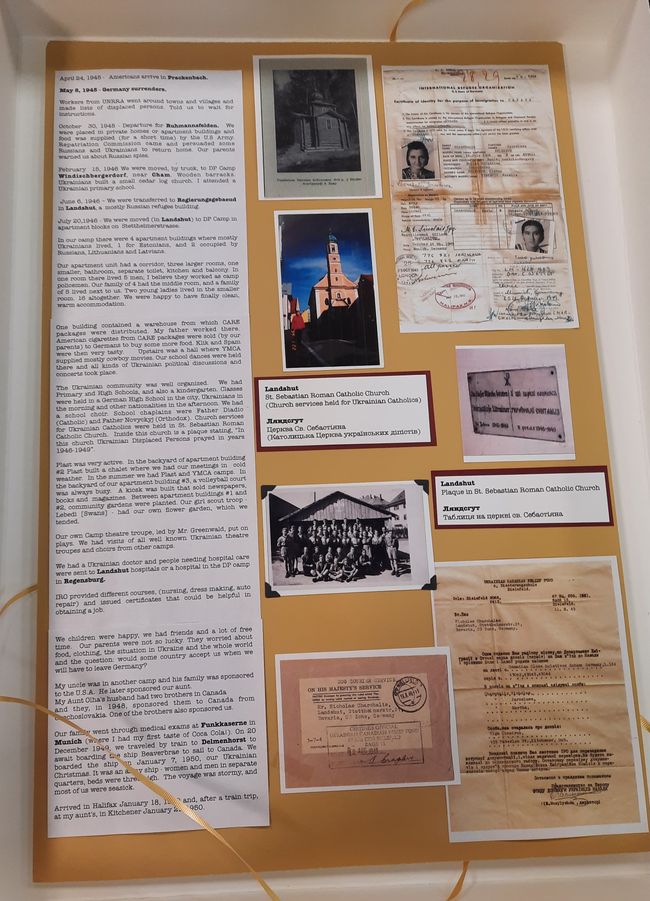

In essence, it was a small exhibition about descendants of DPs. Many of them have returned to the places where the camps were located, where they were born or where their parents lived for a while. These rather recent photos, taken during visits by descendants, are interspersed with historical images, documents, and life stories of individuals. Especially the private photos are fascinating and provide insights into their DP lives. It was interesting for me to directly interact with the protagonists of the exhibition, as most of them are volunteers who work at the UCDRC once a week.

Harpidetu Buletinera

Erantzun

Bidaien txostenak Kanada