Mit Geschichte(n) um die Welt

vakantio.de/mitgeschichteumdiewelt

Von Bolek, Stanisława - und Agnieszka

प्रकाशित भइल बा: 11.11.2023

न्यूजलेटर के सब्सक्राइब करीं

Saturday, 3 p.m., the bar in the Opera House, Sydney: meeting point with Agnieszka*.

"You're new in town and from there you have one of the best views of the harbor bridge," she wrote to me on WhatsApp. The Opera House is not only the central location in Sydney, near Circular Quay, the large ferry terminal, but also pretty much halfway between my apartment and Agnieszka's.

She grew up in Canberra, the Australian capital, and now lives in Sydney in her early 40s. The sun is shining, it is slightly windy, 25 degrees; the bar is full. I recognize her immediately by her long blonde hair, her face resembles her father's. At least I know him from photos, quite a few of them in fact. Agnieszka and I agreed before we ordered: Sydney is probably one of the most beautiful cities in the world. We talk about traveling, about Australia, about her family history. Even before the first drink, we are deep into the topic: her father Bolek, his first wife Stanisława and their son Marek*, their time in Germany and Austria. About Agnieszka's mother and how she met Bolek after Stanisława's death. We jump from one topic of conversation to the next, back and forth: how she started researching what she knows and, above all, what she doesn't know and would like to know about her work in Canberra. She happily accepts the commute to the office, which takes around three hours each way. Sydney is always worth the trip. In Australian terms, a three-hour drive is nothing. That's just next door. She can also often work from home, so commuting is limited to a few days a month. Agnieszka comes from a Polish-speaking household. She understands the language, but prefers to answer her mother in English. “Why did you actually learn Polish?”

Less than ten years ago, Agnieszka asked the Mauthausen Concentration Camp Memorial for information about her father's fate. Bolek died when she was seven years old. She had heard something about concentration camps after his death, but that was all. At some point she talked to her then partner about it; He asked in astonishment whether she was Jewish. Concentration camp, Jew, many have the connection. "Um, no, well, Pole, well... I don't know," she replied.

And started researching.

Her father Bolek was well over 50 when Agnieszka was born, her mother 17 years younger. She was Bolek's second wife. They both met through a newspaper ad. Agnieszka sits opposite me in a long, light dress and laughs. “That was definitely the Tinder back then.” We both laugh. Yes, that's right!

I found Bolek's name, that of his first wife Stanisława and their son Marek on lists from the Flossenbürg DP camp. I found out that he was imprisoned in Auschwitz and Mauthausen; After the liberation, in a DP camp in Austria, he met Stanisława and her five-year-old son. They married and he adopted Marek. The adoption was particularly important for the small family because they wanted to go overseas. They actually wanted to go to the USA, but the visa for Australia came quicker. Okay, then go there. Australia was not only far away, but also had another disadvantage: here the newcomers had to commit to a two-year work assignment. Often these were activities, hard work, that no one else wanted to do: on sugar cane plantations in tropical areas, building dams or any work in the outback. The families were often separated from each other and this often meant living in collective accommodation again.

The young couple didn't want to wait for the USA's visa decision, which seemed better but was uncertain. Bolek, Stanisława and Marek came to Italy in 1950 and from there boarded a ship to Melbourne.

Decades later, Agnieszka wanted to understand more about her father's story. At the end of 2020 I asked about Bolek at the Mauthausen Archive in Vienna. Peter, the archivist, not only found some information about him, but also the email traffic to Australia, to Agnieszka. He wrote to me that he could try to see if the email address still worked. "Shall I try?"

"Absolutely!"

So a few days later in one of the 2020 lockdowns I had contact with Sydney. Agnieszka already knew a lot about her father and his first family, had been researching for a long time, and even went on a trip to Europe, Poland and Austria in 2014, following in her father's footsteps. She remembered not having received any feedback from Auschwitz, but she had a very good and friendly tour leader in Mauthausen. She also traveled to her father's birthplace, Krakow, researched newspapers in Australia and visited the National Archives in Canberra. She wrote to me what she knew;

She had never heard of Flossenbürg. She hadn't really thought about the time after the liberation or the years before her arrival in Australia. Where should you inquire?

We wrote to each other a lot back then. I quickly received emails back in response to my questions. Agnieszka also remembered her father's friends who lived in Sydney. If she remembered correctly, she said at the time, then they knew each other from Europe. Wachacz* is her name. There was also a daughter and she sent me a contact on LinkedIn, a kind of professional Facebook.

I also looked up Wachacz in my DP database.

Two hits.

This couple was also in Flossenbürg, all five of them, the Wachacz couple as well as Bolek, Stanisława and Marek, knew each other from before Flossenbürg. They stayed together and although they received visas for Australia at different times, they remained in touch - and friends until the end of their lives. “There is also a photo attached,” Agnieszka wrote to me in 2021. Although she has no contact with Marek, Bolek’s adopted son, she does have his address. She asks me not to mention her when I ask there. A difficult and also tragic story. But she could print out my letter and put it in the Australian Post, that might be quicker and cheaper. Some time later I also spoke to Marek on the phone, or rather to his wife. Marek was already seriously ill at that time. Above all, he repeated several times that everything he had had been burned. “Nothing left! - Nothing left!” I spoke a little with his wife, at 12 noon in their case, in Hamburg in the middle of the night. We agreed that she would contact us if she found anything. I don't know whether Marek is still alive today. Maybe I'll get in touch with the family again soon. They live “only” four hours from Sydney by car.

It's not entirely clear what happened at the end of the 1950s, Agnieszka tells me again, but it is very likely that Stanisława, Bolek's first wife, committed suicide. At this point they had been in Australia for about eight years. The relationship between Marek and Bolek was not particularly good. When Stanisława was no longer there, their contact broke off. It is difficult to say today why Stanisława probably decided that he no longer wanted to live. Perhaps a court case at the time and the stress surrounding it was a trigger, Agnieszka could imagine. But she doesn't really know much about it. There was no open dealing with it in her family. It was more like silence.

From research on displaced persons (DPs), I know that suicides occurred disproportionately among (former) DPs. The many years of further life in the camp after surviving as prisoners of war, concentration camp inmates or civilian forced laborers, the great ignorance of what will become of you and how your family is doing, was additionally traumatic for many people. The years of waiting, hopelessness, future plans and the disappointment plunged many into deep depression - even if it was not called that or even known at the time. In the collective accommodation of the DP camps in the transitional state, it was difficult to build a new, or even for the first time, truly civilian life. Bolek and Stanisława were still rather young when they were in Flossenbürg in 1946: she, around 30, was a little older than him. Stanisława's fate during the Second World War is not clear. All I know is that Warsaw was considered her last place of residence in Poland. The name of the small town where she was born exists several times. I suspect her birthplace is between Olsztyn and Białystok, about 200 kilometers northeast of Warsaw. The emigration documents note that she was a rather short woman: 153cm; plus: black hair, green eyes. In the photo next to it: slightly wavy, shoulder-length hair. She gave her occupation as a farmer. When applying for a visa to Australia, she also enclosed a certificate: as a displaced person, she had taken a course as an agricultural worker; Bolek works as a car mechanic.

Agnieszka doesn't know where the couple and their son Marek worked after arriving in Australia, and I haven't found anything about it (yet).

After the liberation, Bolek was in his mid-20s and spent two years in concentration camp custody. The National Socialists had accused him of sabotage.

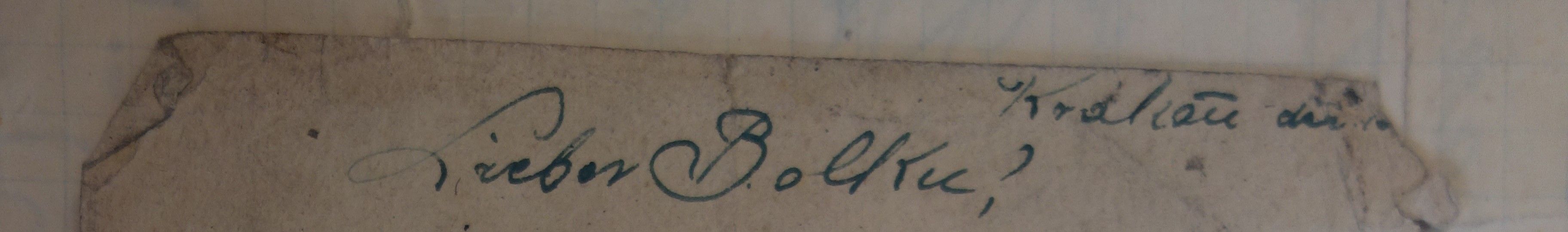

In one of his compensation files, he himself wrote: “I was arrested from home by the GESTAPO (...) because of belonging to the underground movement.” As evidence, he enclosed several letters from the concentration camp, including one from a friend Zofia from Krakow, perhaps his first girlfriend. The SS stipulated that all concentration camp mail had to be in German. Everything else was not delivered. It is unclear whether Zofia knew some German and therefore wrote to Bolek herself or needed someone to translate. One of the cards lovingly says: “Dear Bolku!

(…) I think so much about you, today I dreamed so beautifully about you. That you came to me and (…?) asked if I always liked you as much as I did at school? Do you dream of me too, because I have often dreamed of you and think about you a lot. Please write to me if (?) can send you cigarettes or (?) food. That will be a great joy for me. I can do everything. I am healthy and otherwise doing well. (…) I would like to send you (?) a picture of me but I don't know if I can? (…) When you write the next letter, more of me will fall into your head. Do you still love me as much as I love you? I wish you all the best this year, hopefully it will be better for us. Many greetings, Zocha.”

Next to it is a letter from his parents dated December 26, 1944:

"Dear son! (..) Christmas was very sad. We always like you. (…)” .

According to the documents I know about Bolek, he did not return to Poland after the liberation. It was only in the 1960s, after he had accepted Australian citizenship, that he returned to Europe and Poland for a longer trip.

I translated and sent the file to Agnieszka during our first email contact. But she doesn't want to watch it yet. “That would somehow be a conclusion, maybe even the end of my search. “It’s somehow very personal and it’s my father.” So the compensation file remains untouched by her for the time being.

Shortly before we finished our margaritas and it was getting hot even in the shade, Agnieszka said that she also had other photos somewhere, of Bolek and Marek laying a wreath of sorts and of the time before they boarded the ship to Australia.

A WhatsApp in the early evening, I'm walking home, the harbor in view, the opera house behind me. Agnieszka: “Thank you for coming to town! I’ll look for the photos and let you know when I find them.”

* Name changed.

न्यूजलेटर के सब्सक्राइब करीं

जबाब

यात्रा के रिपोर्ट ऑस्ट्रेलिया के ह बा।