Wir reisen, also sind wir

vakantio.de/wirreisenalsosindwir

Bolivia: Potosi

Uñt’ayata: 07.11.2018

Yatiyäw qillqatar qillqt’asipxam

From Cochabamba to Potosi, there were once again only night buses to choose from, at least if you wanted a decent bus that offered some comfort for the long journey. We woke up early in the morning and realized that the bus had stopped and everyone was hurriedly packing their things to get on another bus. Another breakdown! It was hard to believe! Although the driver assured us several times that a replacement bus would come soon (on further questioning, he admitted that it would still take about 1.5 hours), the other people flagged down other buses that passed by. Eventually, only Jörg and I and a few others were left, so we decided not to wait for the replacement bus and also stopped another bus. It wasn't far to Potosi anyway. And so, we soon found ourselves in a pretty crowded junk bus that belonged to the same bus line, so we didn't even have to pay extra. About an hour later, we arrived in Potosi.

Since the bus terminal of Potosi is located quite far outside the city, we asked a young woman how much a taxi to the city would cost. She immediately offered to share a taxi with her and her mother, who was in a wheelchair. Of course, we accepted the offer, loaded the wheelchair and our stuff into the car, and drove off. When we arrived at the hotel, we unloaded all our stuff from the car, and the car drove off. And then we realized that we were missing a bag! We had forgotten Jörg's small shoulder bag in the taxi! It just couldn't be true!!! I had assumed that he had the bag with him, as he usually did. In fact, it was probably lying somewhere between the folded wheelchair, so it didn't catch our attention in the middle of unloading in the middle of the street with honking cars behind us, saying goodbye to the ladies, paying the taxi, and ringing the hotel doorbell. It was heartbreaking! Fortunately, we didn't have anything valuable in the bag, except a few Bolivianos and an expensive piece of cheese that we had bought as provisions. But Jörg is attached to the bag itself, so once again the situation resembled a disaster. After we had put our stuff in the room, we were already halfway back to the bus terminal to look for the taxi driver when the hotel owner knocked on our door and said that Karina had just called, the young woman who was in the taxi with us. She noticed that we had forgotten our bag, and the taxi driver was already on his way to bring it back to us. She even gave us the name and phone number of the taxi driver. And indeed... 20 minutes later, the bag was back... we really had a slight déjà vu of our time in Tela, Honduras. We were so lucky for the second time and we met such kind and friendly people! So, our Pachamama ceremony with the Yatiri in La Paz had paid off, we thought with a wink.

After this more than bumpy start in Potosi, we rested a bit in the room before going into the city to have a look around and find a laundry. Every foreigner we met along the way asked us if we had seen an open restaurant. It occurred to us that today was Sunday. Other travelers had already told us that Potosi was like a ghost town on Sundays, and as it turned out, even the restaurants weren't open, and all the gringos were desperately searching for something to eat.

On this Sunday, there was also a procession in which the Virgen (of something) was carried through the city from the Iglesia de la Merced, and of course, we watched the spectacle.

We even met a couple from Austria again, whom we already knew from Torotoro (you really meet the same people again and again on the gringo trail), had a longer conversation with them, and eventually found ourselves looking for a restaurant for a joint dinner.

When the Spaniards conquered South America, they were long in search of the legendary El Dorado, which they never found. Instead, they found the Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain) in Potosi, which was full of silver and other minerals. In 1545, the city of Potosi was founded, and from then on, the extraction of silver began. Potosi was once the largest and richest city in the Americas, and was even considered one of the largest cities in the world at that time. Even today in Spanish, there is a saying "Vale un Potosi," which means "it is worth a fortune".

No one knows exactly how much silver the Spaniards brought from Potosi to Europe, but it was an immense amount. The indigenous people were forced into the mines as slaves or cheap labor. Apparently, they also attempted to use slaves from Africa, but they were not only too big for the narrow tunnels, but also did not survive long due to the altitude (Potosi is located at 4,067 meters above sea level) and died in large numbers. Only a few survived and were then used elsewhere (e.g. in the jungle), as a bought African slave was too expensive to die in the mines after a short time. But the indigenous people were ruthlessly exploited. They worked 12-hour shifts every day and even slept in the mine, so they didn't see daylight for months. The working conditions were catastrophic, people died from silicosis (silicosis), accidents, collapsing shafts, or contact with mercury during the smelting process. It is estimated that during the 300 years of Spanish colonial rule, 8 million (!!!) people lost their lives at Cerro Rico.

In the 19th century, the silver deposits began to decline. The boom times of the city are long gone and poverty began to spread. There is still silver in Cerro Rico, but only in small quantities and of poor quality. In the meantime, the extraction of lead, zinc, and tin has gained importance.

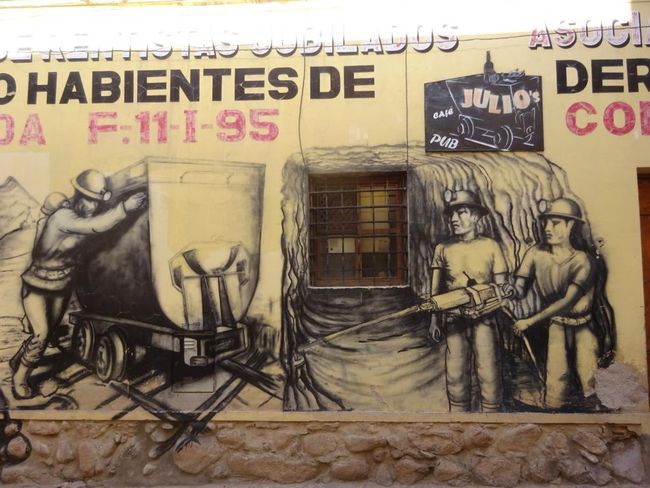

Still today, 15,000 men (and about 100 women) descend into the mine every day to seek their fortune. The working conditions have hardly changed since the 16th century. The work is still very dangerous as the rock is blasted with dynamite. And the majority of men who start working in the mine at the age of around 18, die at a young age (around 40) from silicosis, caused by inhaling fine dust, which leads to lung fibrosis.

Today, the mines belong to large cooperatives, from which the miners buy the mining rights and then extract the rock on their own account. If you're lucky, you can live for 30 years from a tunnel driven into the mountain, if you're unlucky, you won't find anything in the chosen spot. If the whole mountain could be x-rayed, it would probably look like Swiss cheese, so many shafts have been blasted into the rock over the centuries. There are probably about 5,000 shafts, or so we are told.

For tourists, taking a tour of the mines is considered a highlight of a trip to Bolivia, although it is not without its dangers. Therefore, when booking the tour, you have to sign that you acknowledge the risks and that the organizer declines any liability. It has been forbidden for several years now to carry out explosions in the presence of tourists. Of course, we couldn't miss out on this and booked a tour of the mines.

The next morning, we were picked up at the hotel and then we went to change clothes. We were equipped with coveralls, boots, and also helmets and headlamps. There were even boots in Jörg's size!

The tours are led by former miners who know the mountain well. This gives you a really authentic and interesting insight into their lives. The miners are also very proud of their profession, they like to talk about their everyday life, and seemingly take their early death lightly (at least that's how it seems outwardly), questions about that and about the notorious silicosis are dismissed with a shrug. Nevertheless, it is common for alcohol to be consumed in the mine, and it's the strong stuff to cope with the fear. Furthermore, the workers chew coca leaves in large quantities to suppress hunger. Food cannot be taken into the mine, or it would become inedible immediately due to the omnipresent dust. So instead of lunch, there is coca.

First, our tour took us to the mine workers' market. Potosi is probably the only place in the world where you can legally buy dynamite, just like that in stores. Even outside the city limits of Potosi, in the rest of Bolivia, it is highly illegal, so it is not suitable as a souvenir for home, our guide laughed. In the process, he dropped a stick of dynamite to demonstrate to us that it doesn't just explode. But I still flinched quite a bit when it hit the ground, I can tell you. The dynamite is enriched with nitrate to achieve a larger blast effect. A stick of dynamite, a packet of nitrate, and a fuse cost 20 Bolivianos (about 2.90 Swiss francs). In the store, you can buy everything the miners desire: dynamite, work equipment, protective clothing, helmets (there are even helmets from Germany available, but they are unaffordable for most workers), tools, beverages, food, coca.

It is customary on the tours for the tourists to buy gifts for the miners at the market, things they need in their everyday lives. The options are: dynamite for work, fruit juice for health, coca leaves against hunger, or alcohol against fear. When Jörg asked which gift was the best, our guide grinned and said, a Bosch drilling machine, type whatever, costs about 1500 dollars. Well, clear question, clear answer. We then decided on one of the other suggested souvenirs and bought a portion of dynamite and a bottle of fruit juice each. Yes, that's right, it was the first and most likely the last time in our lives that we bought dynamite. Shopping in a slightly different way.

Equipped with our gifts, we then set off for the mine. We had signed up for the Spanish tour, where there were only five of us in total. A young guy and an older couple from Argentina. However, the older couple soon gave up, as it was quite exhausting to crawl through the narrow and deep shafts and climb down to the lower levels. Furthermore, one always had to be careful of passing mine carts, as they cannot brake. Along the way, we kept running into acquaintances of our guide who answered some questions and gladly accepted our gifts.

Our guide mentioned that he himself still goes into the mine when there are no tours. There is always work in the mountain. If you can't acquire a concession for your own tunnel, you can be hired by other "bosses". Or you offer your services as a cart pusher to transport rocks and excavated soil from the mountain (the cart guys never stop to talk to us because they are paid for each trip and are always under time pressure), or as a cleaner. There is always work in the mine, he repeated it again and again. In Potosi, it is considered a disgrace if men beg for money in the city, those are all lazy guys. Only women are allowed to beg, men have to go into the mine. There is something for everyone to do in the mine. Even if you are missing a leg or an arm, that's no excuse. Of course, you can't push a cart with just one leg, but you can certainly still drill blast holes into the rock with the huge drill, you don't need 2 legs for that. We swallowed hard. Some of our disability benefit recipients and unemployed people in Switzerland would probably be quite surprised here.

He asked one of the "bosses" in the tunnel how much he would pay us if we wanted to supplement our travel money in the mine. 150 Bolivianos a day, said the boss, about 21 francs. Um, thanks for the offer, but no thanks. Sure, for Bolivian standards, that's probably not a bad wage, but the working conditions are simply too precarious. It is torture to crawl through the narrow shafts, it is alternately hot and cold. The climbing down to the lower level was even more difficult than our trip to the Caverna Umajalanta in Torotoro. You climb through narrow holes, over steep slopes, cross gaps in the rock on a narrow wooden plank laid in the way and constantly have to be careful not to fall somewhere or bump your head badly. But the worst thing is the dust...the ubiquitous, horrible dust. Although we had a cloth tied in front of our mouth and nose, I still felt for 3 days that my whole face, my mouth, my nose, my windpipe, lungs, and insides were full of this dreadful dust.

We only climbed down to the 2nd level out of many and visited 2 men there. One was just about to chip off chunks of rock with a pickaxe, while the other prepared holes with a huge drill where dynamite sticks would later be placed. Normally, explosions take place around noon and in the evening, we were told. Probably after the tourist groups have left the mountain. As we had already done in the amber mine, Jörg also bought a small stone with silver from the worker here, which he had just hacked out of the rock. "Fresh silver," laughed the man. Again, we paid about 2 francs too much, of course, for such a tiny stone, but we hoped that the man could have a good beer with his colleagues in return, just as the miners in Simojovel did back then. And in return, we received a truly special souvenir, a memento of hell on earth, so to speak, because that's what it is here in the truest sense of the word.

On the way back, we actually encountered him, the devil. It is a small statue made by the workers, to which they make sacrifices. As religious and devout as the men are, it is not God but the devil who rules down here. They offer alcohol, coca leaves, and cigarettes as sacrifices to ask for luck, successful days, and good health. We also donated a cigarette for the well-being of the men. Our guide lit it, took a few puffs, and then put it in the mouth of the devil.

The men work in the mine for 5 days a week. Those who own mining rights for a tunnel are their own bosses and can manage their time themselves. Those who are hired are paid according to their performance. On Saturdays, they only work in the morning. At noon, there is a market where the miners can sell their minerals to processing companies. In the afternoon, they go to the bank to cash their checks. The banks are only open on Saturday afternoons for the miners, access is only possible with an ID. This is mainly to protect the miners from robbery, as they sometimes carry large amounts of money. Afterwards, the group's profits for the week are divided, and then it's time to buy beer. On Sundays, they enjoy themselves before going back to work in the shaft on Monday.

It truly is a tough life here, and once again we leave the mine with mixed and somewhat uneasy feelings, but more grateful than ever for all the privileges that have been bestowed upon us. For our life in an affluent country, for good working conditions, secure jobs, decent wages, for our good education. No, we wouldn't want to trade, no one would. These feelings echo intensely throughout the day, all these shocking impressions don't let go of us (fortunately) so quickly.

We spent the rest of the day wandering around the city and visiting the many churches and colonial buildings, remnants of its former glory.

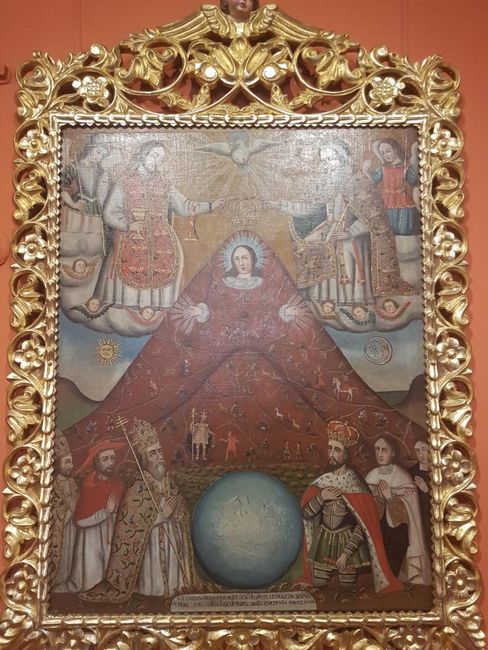

The next day, we visited the Casa Nacional de la Moneda, a major attraction in Potosi and definitely one of the best museums on the continent. The visit is only possible with a guided tour. Since it was the next available tour, we did the tour in English and were assigned a guide who apparently used to be a history professor and gave his explanations with great passion and theatrics.

This is a former mint that was put into operation by the Spaniards and where the immense amounts of silver left the New World in the form of coins towards Europe. This silver soon flooded the whole world and is considered the first global currency, so the Potosi Mint was considered the most important mint in the entire colonial empire.

The first coins were made by hand with a coin hammer, only the silver weight counted (1 ounce of silver = 1 peso) and not yet a beautiful shape, which is why the coins were very uneven. Since silver is very soft, it was common at that time for people to bite off pieces of the silver on the edge of the coin, causing it to lose more and more weight.

Later editions were alloyed with copper to make the material more resistant. Additionally, the serration at the edge of the coin was introduced so that it could be recognized if someone had bitten off pieces.

One theory even states that the dollar sign originated in Potosi. All coins were marked with a symbol indicating the origin of the coin. On the coins from Potosi, the letters P, T, S, and I were superimposed, as a sign for "Made in Potosi". If you only take the S and the I, it creates the dollar sign.

In addition to old coins, the museum also displays original wooden rolling mills, which were imported from Austria in the 18th century and powered by horses. The transport of the machines from Austria took a long time, as the machines were delivered in individual parts by ship and had to be transported from the coast to Potosi by llamas and horses. The silver was first poured into narrow bars and then rolled to obtain better mechanical strength. The coins were then punched out and minted. At times, even a minting machine designed by Leonardo Da Vinci was in use here.

Later, the old machines were replaced by steam-powered ones, which could produce 40 coins per minute.

In 1909, the silver for the coins was replaced by copper, nickel, and zinc, and electric machines were used.

The mint was in operation until 1951, then came the end. Today, Bolivia's banknotes and coins are produced abroad.

The tour was really incredibly interesting and a visit to the museum is highly recommended. We should actually have to pay extra for photos, which we didn't do. But since many in our group had a "photo license", it didn't become apparent that we were taking guerrilla photos the whole time.

In the same afternoon, we wanted to continue to Uyuni and took a bus from the old bus terminal. Since we overslept in the morning and were consequently running late, we also arrived quite late in Uyuni in the evening.

Yatiyäw qillqatar qillqt’asipxam

Jaysawi

Viajes ukan yatiyawinakapa Bolivia markanxa