No poop - Everything is fine in Bolivia!

Được phát hành: 15.12.2016

Đăng ký tin

We have been in Chile for a few days now and it is time to look back on our unfortunately short but eventful journey through Bolivia.

The first days in Copacabana and on Isla del Sol in Lake Titicaca were wonderfully peaceful, just right to relax after the busy days in Peru: Yes, traveling can be quite exhausting ;-)

Lake Titicaca is the highest navigable lake in the world and so huge that our Lake Constance would fade in comparison, it would fit into Titicaca 15 times. We wanted to fully experience the magic of the lake and spent 3 days on Isla del Sol, a beautiful island without cars, alarm systems, and noise, but with lots of landscapes and animals. There are only 3 tiny villages on the island, of which you can only stay in two. We decided to stay in Challapampa in the northern part, which was the right decision, the south had many expensive eco-hotels, but there were no locals or anything else interesting. In Challapampa, a sleepy little village awaited us, with only 2 or 3 small huts to stay in, we chose the hut with the best view of the peninsula. It was spring-like warm during the day, but at night it got freezing cold due to the altitude of 4000m above sea level, but we were well equipped with alpaca and merino clothes and were awakened the next morning by the house goat, who was grazing the grass in front of our door. During our days on the island, we probably encountered far more animals than humans, herds of pigs and sheep, a few alpacas, and especially cute donkeys, which we enjoyed very much. On the second day, we hiked to the Inca ruins at the northern tip of the island and discovered the footprints of the first Inca there, who were sent to earth by their father, the sun god, to bring order and found a city (today's Cusco). A few days before our border crossing, Bolivia had declared a state of emergency due to an enormous water shortage, and on Isla del Sol, we saw and felt the effects of the lack of rain: in the afternoon, no water came out of the pipes and the earth and grass were very dry. But on the second night, the long-awaited rain finally came, and the rainy season started with a bang the next morning, our last day on the island! The only problem was that we had set off for the hike to the southern part of the island at 6.00 in the morning and were caught in the rain (since the rainy season had been delayed, Tömmi had left his raincoat on the mainland). But it wasn't just rain that poured down on us, hailstones, snow, and even a whirlwind made the hike anything but a walk in the park. In addition, we were also under a certain time pressure, as no one could tell us exactly when the boat would leave for the mainland, it was just "sometime in the morning". Although the rainy season could have waited another 3 hours, we were happy for and with the locals who accompanied our march with songs of joy and off-key brass music. When a girl showed us the way to the harbor and I asked her why she wasn't in school, she explained to us that there is no school on rainy days! I wouldn't mind having that rule in Germany either ;-) We arrived at the harbor just in time, along with about 50 lazy tourists who had stayed in the south and hadn't noticed the hail and rain. The little boat was then crammed with all the passengers (4 life jackets for 50 people), the gunwale was at water level, and in the middle of the lake, both engines even temporarily shut down … nevertheless, we made it back to Copacabana, with dry feet again, and a little later, we were already on the bus to La Paz.

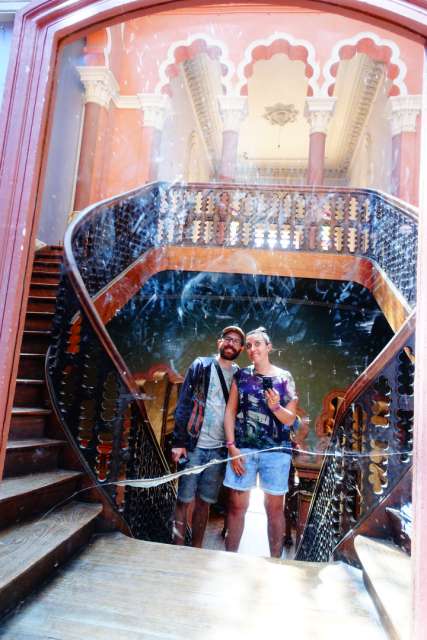

In La Paz, we treated ourselves to the luxury of a hotel for the first time, as there were only party hostels to choose from, and we really didn't feel like being surrounded by the typical "I'm just here for the Death Road and the Salt Flats" crowd. Besides, I wanted to take a shower without the risk of getting an electric shock, because the showerheads here in Bolivia are usually operated with adventurous electrical cable constructions and when you turn on the faucet, the electricity usually flows through the user as well. In combination with water, it's a thrill every time. Fortunately, our hotel Milton had a gas shower and exuded the charm of the Grand Hotel Budapest, we felt very comfortable.

La Paz, often mistakenly referred to as the capital of Bolivia, with its 750,000 inhabitants, is located in the middle of the Andes. The metropolis nestles into a huge gorge at an altitude of about 4000 meters. On the slopes, where the icy wind blows down, you can find the most meager dwellings, and on the high plateau above La Paz, there is even a huge settlement of the poorest, El Alto. La Paz and El Alto used to be one city, but they have been separated since the mid-1990s. Those who can afford it prefer to live as far down as possible, but the majority cannot afford it, and so El Alto is growing rapidly. To reconnect the two cities in terms of infrastructure and symbolism, Morales hired the Austrian cable car company Doppelmayr to span a total of 4 cable car lines between La Paz and El Alto.

La Paz itself immediately sucked us into its sympathetically chaotic whirlwind of a modern city and traditional village life and the city reflects the craziness of President Morales and the whole country quite well.

Our Curiosity Hit List:

1. San Pedro Prison: In this prison, there are only 15 guards, around 2,000 male inmates (who pay different rents depending on the sector and sometimes even live quite well with their wives and children who are allowed to come and go freely), market stalls, restaurants, souvenir shops, and loosely hanging corrugated iron parts that are lifted every minute to throw small packets of white powder onto the surrounding streets, because the prison city is in the middle of La Paz. Until a few years ago, there were guided tours for tourists, who mainly learned about the prison from the book "Marching Powder" and at the end of the tour were allowed to sniff a pinch of finest prison coke through their gringo noses. Brad Pitt has secured the film rights.

2. The new Bolivian time: At the congress building, the Bolivian and rainbow flags flutter, above them, a clock shows the time, but you have to look twice to read the time correctly because the clock runs counterclockwise. The government led by President Evo Morales wants to make a statement and eliminate the traces of the colonizers. A clock on the southern hemisphere turns the other way around compared to a clock on the northern hemisphere, and in Bolivia, a new era has begun with the first indigenous president, according to the explanations for the reverse clock.

3. Calle de las Brujas - the Witches' Market: Here you can find everything you need to survive, from herbs to snake meat and dried llama and alpaca fetuses. The witches here perform magic in a hurry, be it for falling in or out of love, a stroke of luck with money, or potency, they have a magical potion for everything. But we not only visited the (nowadays very commercial) Witches' Market in downtown La Paz, but also the Witches' Street in El Alto, where the locals have their future read in coca tea made from coca leaves. By the way, you can only become a witch if you have been struck by lightning or have had another near-death experience, for example.

4. Empowerment 2.0 at Cholitas Wrestling: The Cholitas are the iconic symbol of Bolivia, round women with long braids, short pleated skirts, and the typical bowler hat. They are Ladies with skirts, charm, and a bowler hat! Cholitas always come from good families and are often very rich due to their business acumen and diligence. They like to show this off with their golden or silver smile, and a complete Cholita outfit costs several thousand dollars: several colorful and intricately embroidered pleated skirts to highlight the curvaceous hips, followed by a colorful puffed sleeve blouse and a hand-knitted cardigan. Finally, the Bombín, which traditionally comes from Italy and reveals whether the Cholita is single, married, divorced, or widowed based on its position on the head. The whole Cholita is held together by a colorful carrying cloth called Aguayo, in which everything that we carry around in a handbag can be found, plus often a human, alpaca, or sheep baby. The bowler hats are a remnant of the British railroad workers, who found that the felt cap with a narrow brim did not provide enough shade against the glaring Andean sun and therefore gave their hats as gifts to the highland women. These have been part of the traditional folklore for 100 years now. However, the Cholitas not only love hats but also love empowerment, and almost every Andean village in Bolivia has a Cholita football team. But apparently, playing football is not enough for the girls in El Alto - twice a week, they step into the wrestling arena there and outshine any WWF pro. We couldn't miss this spectacle and the Cholitas really gave it their all: jumps from the ring barrier, hair pulling, bribable judges, and stirring up the audience made for a great evening for us!

5. President Morales' legislation: Morales has tried to stimulate population growth through numerous laws. His "best" ideas were the abolition of condoms and a special tax for childless women over 28 years old. However, the Bolivians don't put up with everything and demonstrated for a few days until he revoked his laws again. Currently, he is trying to be elected president for the third time, but he already cheated the last time, so we are curious to see what he comes up with this time!

After freezing in La Paz and having to buy alpaca sweaters again, we flew deep into the jungle to Santa Cruz De La Sierra. Because everyone had warned us about the horror bus rides in Bolivia and flying was not really expensive, we chose the plane and an hour later, we were already in tropical Santa Cruz. The arrival in Santa Cruz can be described as follows:

phew, it's pretty hot - oh, palm trees everywhere - look, a parrot - wow, there are only fast food stores here - and ice cream parlors - what kind of taxi are we actually in? - why? - Look ahead! - oh, there's no dashboard - yes, the displays are all on the right, but the steering wheel is on the left - well, it's running, so it's probably allowed here, better than the horse-drawn carriage next to us - uh, Tömmi, where are we? - why? - there are only white people from the 18th century here - what, where? - oh dear, they look creepy - wuaa, there's a woman carrying a severed calf head under her arm - yes, it will probably be cooked for soup - we urgently need mosquito spray, the critters are feasting on me - Finally, there's our hostel up ahead!

And in Santa Cruz, there wasn't much else to see. The white people from the 18th century turned out to be Mennonites. I found them creepy with their dead gaze and old-fashioned behavior, so I read several articles that all confirmed my impression that they are totally loco: laughter, having fun, and making music are forbidden ... well, then they shouldn't be surprised that no country except Bolivia wants them and Bolivia probably only because of the money.

In addition to expensive villas with luxury cars, expensive bars, and shopping malls, Santa Cruz doesn't really have anything interesting to offer, so we took several trips to the surrounding jungle. We felt more like in Miami, the city contradicts everything that is associated with Bolivia, which makes it even crazier that it is located in the middle of the jungle.

In the botanical garden, which is so large that we got lost in it and it has more to do with wild jungle than with a garden, we found free-living sloths, turtles, monkeys, and alligators. We actually wanted to see jaguars and the Jesuit missions, but since we felt like the only tourists in St. Cruz and all tour agencies canceled on us due to too few tourists, unfortunately, that didn't work out. So we went to the Güambé Park to relax, a private resort with a butterfly and bird farm, a monkey island, and many different swimming pools, beautiful!

From Santa Cruz, we flew back to Sucre, the capital of Bolivia. Sucre is very cozy, but here too we were surprised every day:

1. Zebras regulate traffic here: Bolivia has launched a traffic safety program to teach the anarchistic-impatient car drivers a little more consideration for pedestrians. In almost all major cities, students in zebra costumes perform at dangerous intersections and help especially children and the elderly to cross the street safely, delighting car drivers with their antics. We gave this great project 4 thumbs up!!

2. Just 15 minutes outside the city lies the pink castle La Glorieta, which combines all European architectural styles: Big Ben clock tower, Arab minaret tower, Gothic windows, Renaissance dining room, French water garden, ... The builders, who were awarded the status of the only Bolivian prince and princess, were inspired by their trip to Europe to create this curiosity in pink. Today, the little castle is located in the middle of a military restricted area ... why a military base was built there of all places is a mystery to us, it's not as if Bolivia doesn't have any free space left.

3. In a quarry near Sucre, there are dinosaur footprints to admire on a steep wall that was once the bottom of a freshwater lake. Since the dinosaurs were busy drinking water there and the bottom was very rich in clay, the footprints were well preserved. Plate tectonics did the rest and squeezed the ground plate vertically upwards, so that today you can admire the footprints like an oversized painting. It's pretty outlandish to stand in front of the imprints of Brontosaurus, T-Rex, and Co in a quarry. Unfortunately, however, there is not enough money to protect it adequately. Recently, a huge chunk simply broke off, since then, visitors have to wear helmets ... I'm not sure if that's the right strategy.

From Sucre, we took the bus to Potosí, the former richest city in South America and still the highest city in the world. Unfortunately, there is not much left to see of the city's former splendor today. Although the city has UNESCO status, the former wealth can only be guessed at, most of the magnificent buildings look quite crooked and have peeling paint, rather presenting a sad picture. This sadness and longing for the long-gone silver times hang over the whole city, the people here are quite poor, and most of the men are heavily marked by the hard work in the mines. Once upon a time, vast amounts of precious metals, especially silver, were hidden in these mines. The Spaniards, of course, appropriated these treasures and financed the decadent lifestyle of the Spanish crown for decades. Originally, slaves from Africa were intended to work in the mines, but most of them hardly made it into the mines. The reasons for this are the extreme altitude and cold, which brought death to the unacclimatized Africans. So the locals had to go into the mountain and extract the coveted silver, but they deeply resented such ruthless exploitation of their beloved Pacha Mama (Mother Earth). But money and luxury were tempting, and so the Cerro Rico has been exploited by the people of Potosí for over 400 years, even today, although the silver reserves have long been depleted. These mines are also the only reason why tourists find their way here because you can take mine tours and see the Cerro Rico from the inside. However, for several reasons, we absolutely did not want to participate in such a tour: I'm not a fan of this gawking tourism, where you expose yourself to the extreme suffering of other people for a few minutes, just to have a selfie with a miner afterwards. Since the miners only survive their terrible work with a lot of alcohol and coca leaves, tourists are also required to bring this with them into the mines, so to speak, as an entrance fee. This already says a lot about the inhumane working conditions. Hardly any miner lives to be older than 50, and those who chisel the metals from the stone are at most 40 years old because their respiratory tracts are not protected. They do earn $50 per hour, but if you have to give up the silver spoon by the age of 40 and know that your wife and children are then left to fend for themselves, in my opinion, there is no appropriate compensation for that. The widows "are allowed" to work as stone breakers on the mine grounds in order to support their families, and they often continue this activity until their last day. Boys are allowed to work in the mines from the age of 12, and they do, willingly. Child labor is officially allowed in Bolivia!! Accidents are the order of the day in this mine, hardly a day goes by when all miners come out unharmed. Experts expect the collapse of the entire mine at any moment, as the mountain is already so riddled with holes and not a single mine tunnel meets today's safety standards, in addition, the miners work with dynamite (in Potosí, dynamite is freely available on every street corner). There are now 16 levels underground, and it makes you wonder how long Pacha Mama can stand it. Moreover, Tömmi doesn't really like narrow underground passages, but he did a lot of research and found a museum that is located in the mines and explains the history of the exploitation. We quickly found the only agency that includes this museum in the program, and our guide took us to the mine for an hour. On the way, we met some miners who chatted with us, and the museum was very interesting, albeit oppressive. I found the old Tio (Uncle), the devil, to be the most exciting, who the miners offer cigarettes, liquor, and coca leaves to every day so that he doesn't cause any mining accidents and shows the miners the metal veins. Tio is only in good shape when his cigarette is smoldering and burning nicely, if it doesn't, it means bad luck. We also found it funny that Tio is always horny and every miner strokes and covers his erect penis with coca leaves every day, as Tio is continuously having sex with Pachamama.

In the evening, we were then surprised at the main square with a Christmas market in Bolivian style, including chocolate-covered fruits, but unfortunately without mulled wine.

But now Uyuni was waiting for us, from where we started a tour into the salt flats. Once again, our desert group was great, together with two couples from Switzerland and China, we formed a great team. Our driver Juan Carlos chauffeured us through the desert blindfolded, and we always wondered how he knew the way, as "roads" or paths were hardly recognizable as such. Our guide Bismarck (the list of funny guide names is expanding) had something to say about every natural spectacle and turned out to be a gifted funny pictures photographer on top of that. The endless expanse in the salt flats almost invites you to take the dumbest photos possible, and of course, we did our best ;-) In addition to the salt flats and an overnight stay in a salt hotel, we also got to enjoy a cactus forest on a coral reef (the entire desert used to be a sea, which is why all rock formations there are either former corals or volcanic remnants), multicolored lagoons with flamingos, the Dalí desert, several volcanoes, a geyser field, hot thermal springs, and many vicunas and llamas.

The border crossing to Chile also took place in the desert and, as always, went smoothly, although Tömmi was super nervous because of his vaping equipment, as the Chilean entry requirements are very strict. But the customs officers were having a good day, and now the long journey to Patagonia begins for us. We would have loved to stay much longer in Bolivia because the country has soooo much to offer and the people there are all very warm-hearted, open-minded, and helpful, but unfortunately, we have already booked ourselves into the Chilean Valparaiso for Christmas and bought concert tickets in Santiago for Sunday. But we are also looking forward to Chile, where it is probably much more European.

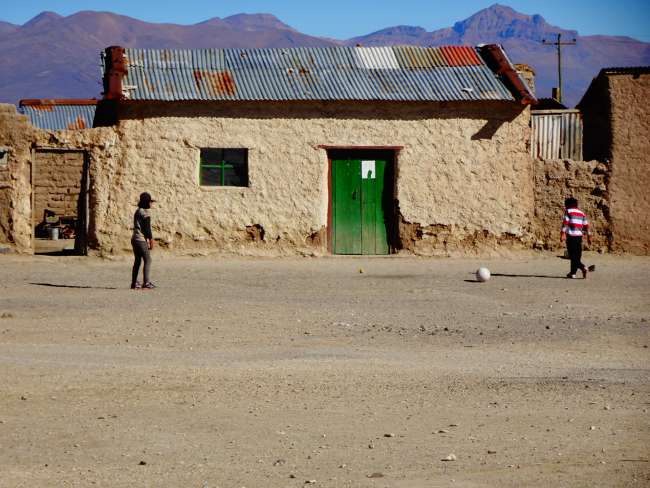

One more note about legal child labor in Bolivia: At first, we naturally wag our moral finger and ask why no one is doing anything about these laws that obviously contradict children's rights. But a second look at the topic is worth it. After I became aware of some posters of the numerous self-organized children's unions, especially in the mining city of Potosí, I read a little about the topic. Yes, in Bolivia child labor is officially allowed, but (as we have experienced it ourselves and have been told) many children also want it! Whether it's the boy on the bus selling comic books or sweets, or the many girls in the restaurants who rush up to the tourists with a beaming smile and show excellent service, none of the children here look tired, sad, or forced. They do their work with utmost dedication and joy, and we don't think that all of them have so much acting talent to pretend that. In order to give themselves and their work a voice vis-à-vis foreign hostilities, the kids here organize themselves in unions and advocate for their right to work in various ways. They just want to contribute a little to the livelihood of their extended families, and in Bolivia, a life is only fulfilled if you work. There is virtually no unemployment here because everyone wants to work and does so, mostly by starting their own business. The Casera principle supports this entrepreneurial spirit: Every Bolivian has a special casera (person) for everything they need in life, a casera for bread, one for sausage, one for clothing, etc. They remain loyal to their casera for life and, in return, receive special offers. This also explains why there is a separate street for every product here. We have often wondered how 100 paint shops can exist side by side, but the Casera principle explains it. This business acumen (almost all shops and stalls here are open 7 days a week from very early in the morning until after sunset) is also reflected in the children. And what about compulsory education? That is also well regulated because the children can choose whether they go to school in the morning or in the afternoon, and they all go to school because the government pays families a bonus if the children go to school regularly. Leisure time and playtime probably don't come up short either because no matter what time of day we pass a school, it's either excursion day or recess ;)

Đăng ký tin

Trả lời

Báo cáo du lịch Bôlivia