the roads behind the Red Rocks

vakantio.de/the-roads-behind-the-red-rocks

Adobe Land

வெளியிடப்பட்டது: 04.05.2023

செய்திமடலுக்கு சந்தாதராகவும்

The older ones among us, those for whom an electric model railway was still high-tech toy in great demand, may still remember the Märklin catalog; unmistakably and always quite prominently featured were the red-silver painted diesel monsters of the "Santa Fe Railroad". They stood for endless prairies and seemingly insurmountable Rocky Mountains, for the conquest of the West, for train robberies, Indian wars..., in short, for everything that a Upper Bavarian country bumpkin imagined the Wild West to be.

And now? The locomotives are now painted white and red, the train station is a better S-Bahn station, and everything else has changed.

Santa Fe enchants with its adobe architecture. There are no high-rise buildings here, and the whole city gives the impression that traditional pueblo architects were at work here. What is particularly fascinating is that even the newest multi-storey buildings are built in the mud construction style that is completely contrary to the right angle.

Of course, not only passing Europeans find this very interesting, but also the Americans themselves find it very attractive, and tourism flourishes.

In all this hustle and bustle, however, you will come across a very special oasis: a long colonnade has been reserved by the city administration for the natives, who are allowed to offer their own artistic objects there. This was the only time so far that I was glad that Bine wasn't with me. This place has the potential for personal insolvency.

Of course, Santa Fe did not fall from the sky, but is an expression of the entire region. Nowhere else in all of North America have the Native Indians been as present in daily life as here. And they are well aware of their role as carriers of an outdated culture. This becomes particularly clear when visiting one of the old inhabited pueblos: After paying a hefty entrance fee, you find yourself in a inhabited farmhouse museum. However, this is neither embarrassing nor uncomfortable (like a zoo factor), but the locals interact quite casually with visitors.

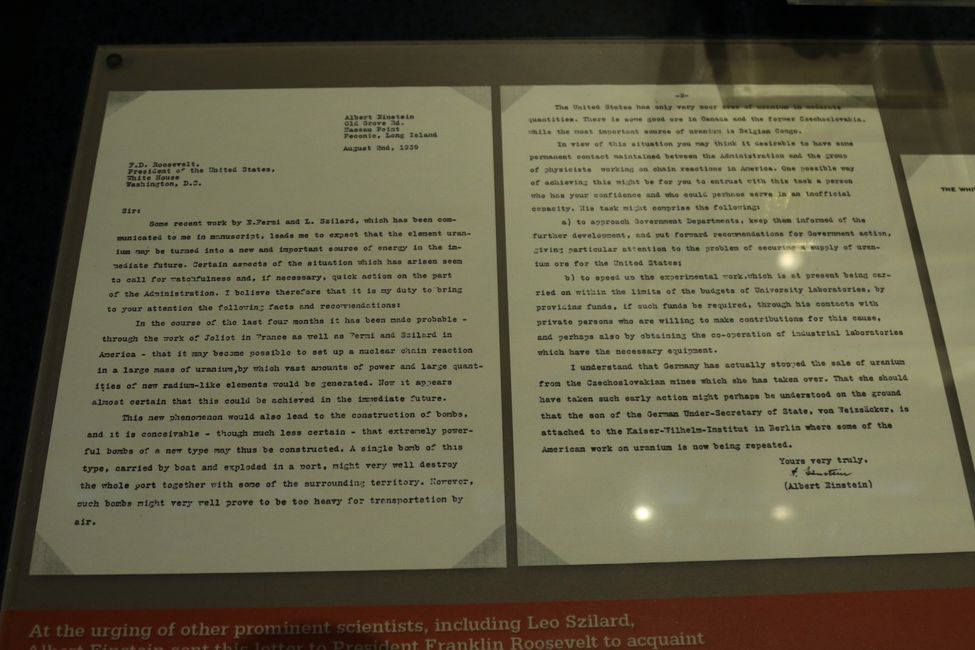

This traditional high-culture landscape does not seem to fit with the complex of Los Alamos. Here, in the desert of New Mexico, a huge laboratory was set up during World War II to develop the atomic bomb. In the museum, two things are of particular interest: on the one hand, the correspondence initiated by Albert Einstein, which ultimately led to the decision to develop this weapon, and on the other hand, the political justifications.

However, you quickly return to the fascination of the Wild West when you unexpectedly come across a gigantic canyon that the Rio Grande has carved into the plateau landscape and you learn that this legendary river originates not far from here in the north of New Mexico.

செய்திமடலுக்கு சந்தாதராகவும்

பதில்

பயண அறிக்கைகள் அமெரிக்கா